Cultivamos Cultura: down the bio-art rabbit hole

Published 23 July 2024 by Roger Pibernat

From July 1 to 19, Cultivamos Cultura held its bio-art Summer School in Sao Luis, Portugal. Roger Pibernat, Makery’s resident columnist for the Feral Labs Network, was there.

Cultivamos Cultura’s Summer School happens in a farmhouse in the middle of São Luis, a small town in the Portuguese Alentejo. The winding roads that lead there stretch the time, making everything slower, even my phone. Bio-art is also very calm; artists set the environment and wait for things to happen, observing and interacting with it very kindly. It’s art that transpires care and love.

I knew absolutely nothing about bio-art before this visit, except that it involved biology in some way. Marta de Menezes, bio-artist and founder of Cultivamos Cultura, says that it’s any form of art that interacts with biology, or Nature, at any point of the creative process. She also explains that purists only accept as bio-art those works that have some kind of biological content in them when exhibited. A video of a recording of microbes, for example, would not be considered bio-art by a purist. I’m told that back in the day it used to be big, even trendy, but is currently considered kind of a thing of the past for many. Those who still practice it, though, are really enthusiastic. After one week soaked in agar, I understand why.

Agar is a gel extracted from seaweed. It’s the medium where biologists grow microbes in their Petri dishes (small round lab dishes). We used it in the first workshop: microbial growth. We mixed it with air-dry clay sculptures and nutrients to set the environment to grow happy microbes that we gathered from different places, such as spit, dirt, rotten fruit… We would later observe them through the microscope.

This workshop is the perfect analogy of Cultivamos Cultura: the summer school is the agar –the medium–; the faculty (the Summer Camp’s teachers) is the nutrient; and the participants are the microbes. You mix the three, and beautiful creatures, organisms and art start to grow.

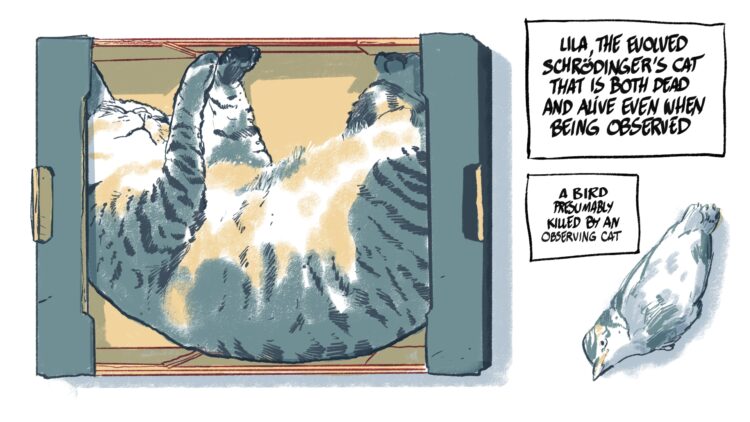

The faculty members were Marta and three more educators: Mark Lipton, Maro Pebo, and Roland van Dierendonck. There were only four participants: Emma Hallemans, Dave Dowhaniuk, Daphne Frühmann and myself. Marta found out over the years that this is the best ratio for both faculty and participants. From the outside, one can hardly tell who is faculty and who is a participant. More than a summer school, it felt like a summer family. A family completed by Anna Isaak-Ross who took care of the practical matters, and arranged the housing. Her children sometimes joined the activities. Starzy and Lila, the cats, complete the squad. I met them all upon arrival, at the dinner table. Before going to bed we were warned: “people here dream a lot, and they are intense dreams”.

During the week, there were seminars, discussions, walks, workshops and activities on different fields of biology. Marta explained that they are not teaching bio-art, they teach biology procedures and techniques, the same used in a scientific lab. It’s the artist’s responsibility to add something of their own to turn it into a creative work. These workshops are to bio-art what drawing or photography lessons are to visual arts.

Daily morning practice

The school program was packed. We started every day with Mark’s morning practice to “engage with sense perceptions, body movement, structural anatomy, pleasure, engagement, self-management and trust”. We were taught to do so with “expressive art, play, and writing, introducing movement resources that promote slowing down for greater health, well-being and longevity”. We were summoned to the yard or the barn at sunrise, and Mark would explain concepts related to a varied field of knowledge, ranging from anatomy to circadian rhythms, flock social behaviour, performance, choreography… We learned about ourselves and our bodies by experimenting with physicality, moving, writing, by drawing a material and immaterial map of our body full of layers of past generations…

Inquiries in the secondary lab

After this, some of us would go to the market to buy food for the day, while the rest prepared the table for breakfast. Food is an important part of Cultivamos Cultura. Marta is a great cook. We would assist her as kitchen hands while she prepared fabulous family recipes like “migas“, barnacles, baked apples, awesome lemon mousse, pork loin, tomato soup, peas soup… I haven’t eaten so much and so good in a long time. Cooking took also quite a while, as couldn’t be otherwise in this slow-paced atmosphere. It was then that I took the chance to ask around a question that had been haunting me since before I left home: why bio-art? Isn’t it like playing God?

“That would imply that you believe in God”, Marta said, and continued “to me, it’s all about Identity”. She proceeded to elaborate with a deep explanation about the philosophy behind bio-art. A huge rabbit hole opened under my feet, and I fell in it. I’m still grasping to the walls with my nails so as not to fall deeper, although temptation is pulling down very hard and I’m willing to let go.

I kept asking around to see what moved others into bio-art. During lunch, Daphne explained that she is exploring, getting her foot in the door into something that she finds very relevant and is eager to enter, as her current job is totally unrelated to her Cultural Studies background and she misses it a lot. She has also recently become the host of Symbiotopics, a very interesting podcast series about bio-art. She considers herself more of a thinker than a maker, but she’s very excited about getting her hands dirty and that’s what brought her here. When I asked her what bio-art is, we engaged in a deep conversation about art itself. “It’s about awareness”, she concluded.

Emma dove into biology out of curiosity. She needs to find out how things work. When asked where that curiosity comes from, she stopped to think for a moment, then said: “I guess I need to understand”.

Being it a sense of identity, relevance and awareness or understanding, bio-art seeks the same as any other discipline. But it does so in direct contact with Nature, talking to it face to face. In the first morning practice, Mark said: “the ratio of salt and sweet water in our bodies is exactly the same as that of Earth; we are not simply inhabiting it, we are the Earth”. In bio-art, artists make art with themselves, it’s self observation and exploration, not only in a metaphorical sense, but also literally.

The meat and bones of bio-art

Bio-art is a very visceral and physical form of art. It can get quite intense, as we could see in the books that Marta showed us, full of blood and guts .

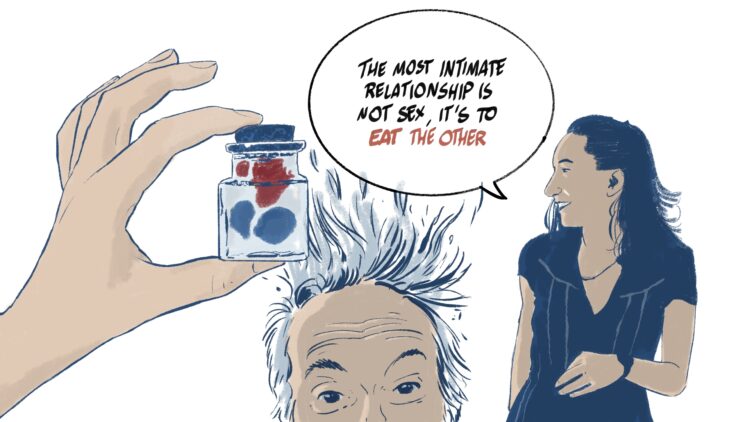

Maro’s talks and workshop confirm this. She told us about her work, and gave insight about our biome, the microbes that conform our bodies. They are living creatures which mould every aspect of our beings, including character: “microbes can make you brave”, she says. We learned that our digestive system is actually part of the outside of our bodies; we are like a doughnut, so to speak, with a very long and intricate hole. Microbes live there, and we interact with them through what we eat. Maro invited us to her transpieces approach, performing a ritual of communion, similar to that of the Catholic culture she comes from, to reverse biosis (loss of our biodiversity). Instead of eating the body of Christ, she proposed to create our own communion bread with molecular gastronomy filled with microbes of our choice. We “cooked” food-balls of what we wanted to become. She summarized this exercise by saying: “The most intimate relationship is not sex, is to eat the other”. Amen.

Bio-tech from haptics to visuals

Roland’s approach to bio-art is more techy. He’s a microscope-geek, and uses bio-haptics – electronic sensors and physical actuators such as buzzers – in what he calls “sensorial knowledge”. His art is to be perceived through the sense of touch as others create music to be heard, or visual arts to be seen. He also told us about DNA data storage (using DNA as a hard drive), and many other bio-weird experiments which I would need to get back to to fully understand and explain.

In his workshop we went for a walk to pick up water from the town pond, under the distrusting vigilance of the townshall president, who Anna soothed saying we would not be taking any of the frogs or fish living there.

Back in the lab, Roland taught us about the different organisms we could see through the microscope. Among these creatures were jumpy rotifers, warmish nematodes and slippery vorticella, which Marta had been hoping to find for a long time and yelled in excitement when finding out they had been in the pond next door all along. We learned how to record these creatures on camera, so we could later use the movies to “paint” in what Roland names “chronomicroscopy”. His technique consists of layering lighter pixels of successive frames, to create an effect similar to that of light-painting in the dark. This reveals that every microbe has its own movement. Roland questions why not classify them by their movement.

Urchinodean offspring

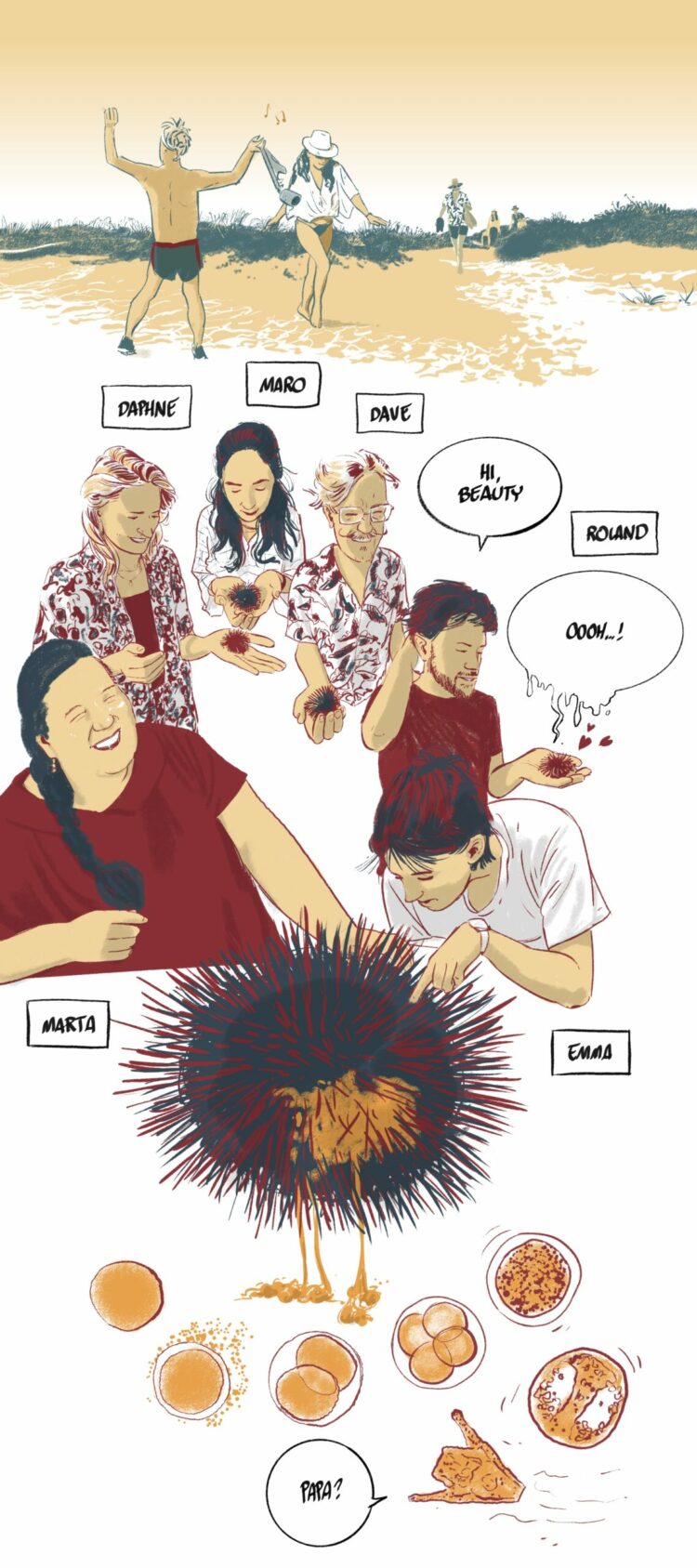

The workshop that really made us a family, though, was fertilizing sea urchins. We took a taxi to the nearest beach, in Vila Nova de Milfontes, where Marta is originally from. By poking our hands into underwater rock holes we would gently pull out the urchins, taking special care not to break their spikes. “Imagine you are breaking their arms”, Marta warned.

This had to be done during low tide, at around 7:30 a.m., after which we relaxed under the sunny but chilly sun, eating a snack, going for a swim and watching the faculty’s stylish dance on the sand at the sound of 80’s hits coming out of Mark’s boom box.

On the way back we filled jars with sea water that we would use to fill the fish tank where the urchins would stay for the rest of the day. Marta explained that sea urchins get excited with waves, which are especially strong during spring. She invited us to hold them in our hands and pretend we were waves. The goal was to make them so excited that they would release sperm and eggs. Only Roland managed to do it by hand. The rest of us needed to inject potassium chloride into their shell with a syringe to get them excited. Roland’s urchin got so excited that filled the whole tank with its sperm. Apparently, Roland is a very sexy bio-rock-n-roll star for urchins.

Next step was to combine the sperm and eggs together in different pairs in a tray of microscope wells. Through the lens, we would witness the process of fertilization and growth of every living animal, including humans. I had studied this at school, but seeing it in front of me has been quite a thing. It all happens very fast: the spermatozoa swim in crowds across to an egg, trying to get in; as soon as one is allowed to enter, the egg creates a membrane in seconds, pushing away the rest of the spermatozoa. After about 30 minutes, mitosis starts (the fertilized egg divides into two cells). 45 minutes later, there are four cells, then eight, and so on until the thing starts to rotate, creates the digestive tube, starts swimming and, before you know it, you are the parent of an adult sea urchin. The whole process takes only five days.

I had to leave São Luis before they were grown-ups, but my new bio-summer-family has been sending pictures and videos of our beloved spiky children playfully swimming in the micro-pool. The urchins that gently gave us their genes were released back in the ocean the day after we picked them up.

Before leaving, I asked Maro: if she were to recommend one book – and one book only – to get introduced to bio-art, which one would it be? She recommends “Art as We Don’t Know It” published by Aalto University and available online for free as PDF. Marta is a contributor. The door of bio-art has been opened.

The Cultimas Cultura summer school is organised with the support of the Rewilding Cultures program, co-funded by the European Union. Roger Pibernat is Makery’s resident columnist for Rewilding Cultures during the summer of 2024.