From e-textile to Grätzel cells, encounter with the taiwanese designer Shih Wei Chieh (1/2)

Published 20 December 2023 by Ewen Chardronnet

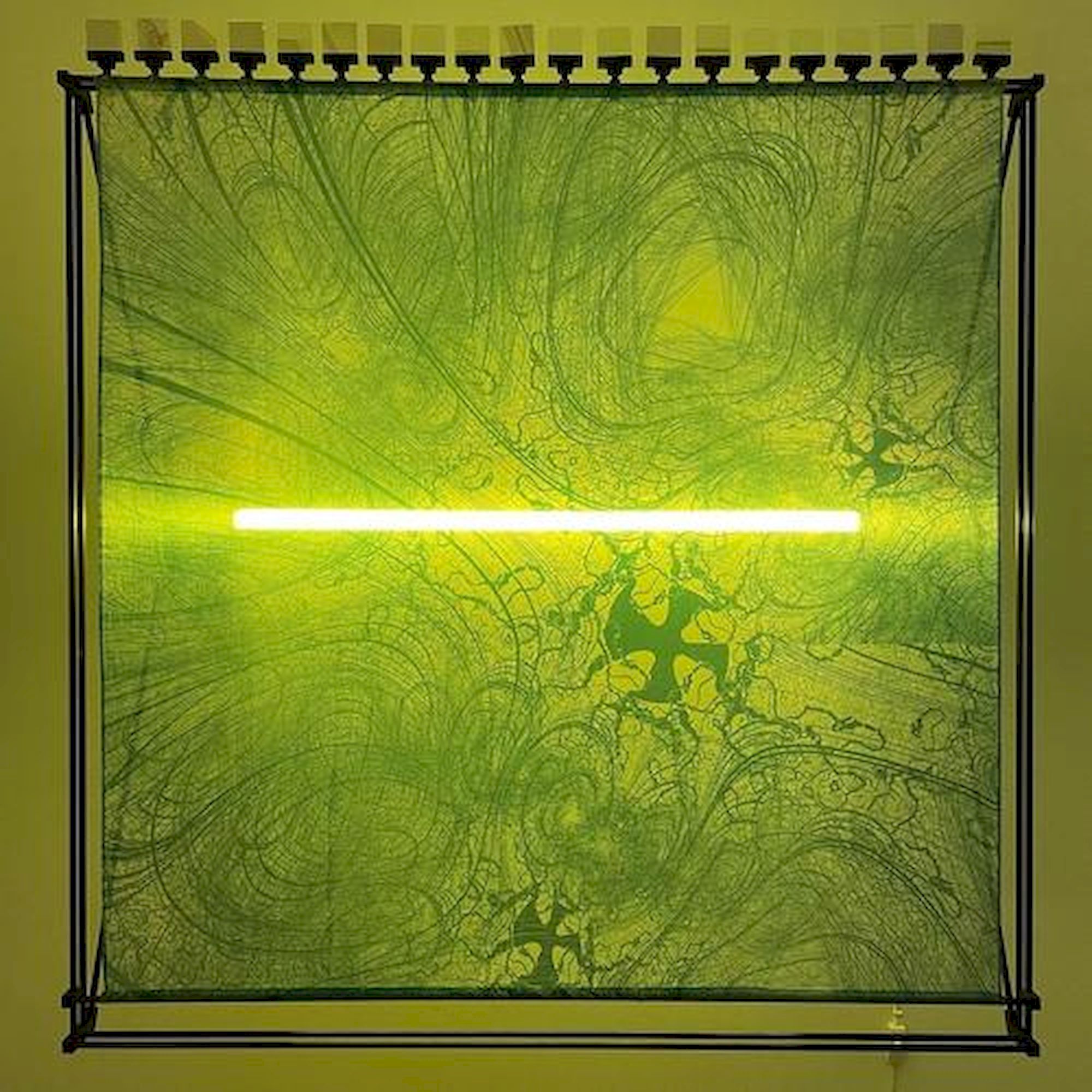

Taiwanese artist and design researcher Shih Wei Chieh was in residence from September to November at Bitwäscherei hackerspace in Zürich. During his residency, Shih Wei Chieh advanced his current research work on dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC), a photoelectrochemical system inspired by plant photosynthesis which, when exposed to light, generates electricity. Cells of this type are sometimes referred to as Grätzel cells, in reference to their designer, Michael Grätzel of the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne. So Switzerland seems the obvious destination for the Taiwanese. Makery wanted to know more about his background and new projects. First part of the interview.

Makery has been interested in the projects of Taiwanese artist Shih Wei Chieh for some time now. Initiator of the Tribe Against Machine workshop, already a landmark event in the e-textile makers world, long-time companion of the Hackteria network in the Pacific, and now with his fairy fingers in the field of Grätzel cells? His European visit as hacker-in-residence at Bitwäscherei in Zürich was an opportunity to get to know this inspired and inspiring designer. And to ask him what his research was in Switzerland. The result is a wide-ranging interview.

Can you introduce yourself and tell us your background studies?

My name is 施惟捷 Shih Wei Chieh (actually last name is Shih, first name Wei-Chieh somehow I didn’t follow the western spec). My background was interactive design in the early 2000s, while Arduino, Max/MSP, puredata, vvvv and Unity were still new. So my training was actually design, not art, however my school didn’t train us to become designers, they let us do whatever was creative.

You’ve been active in the field of merging traditional craftsmanship and contemporary technology, can you tell us where this interest originally came from?

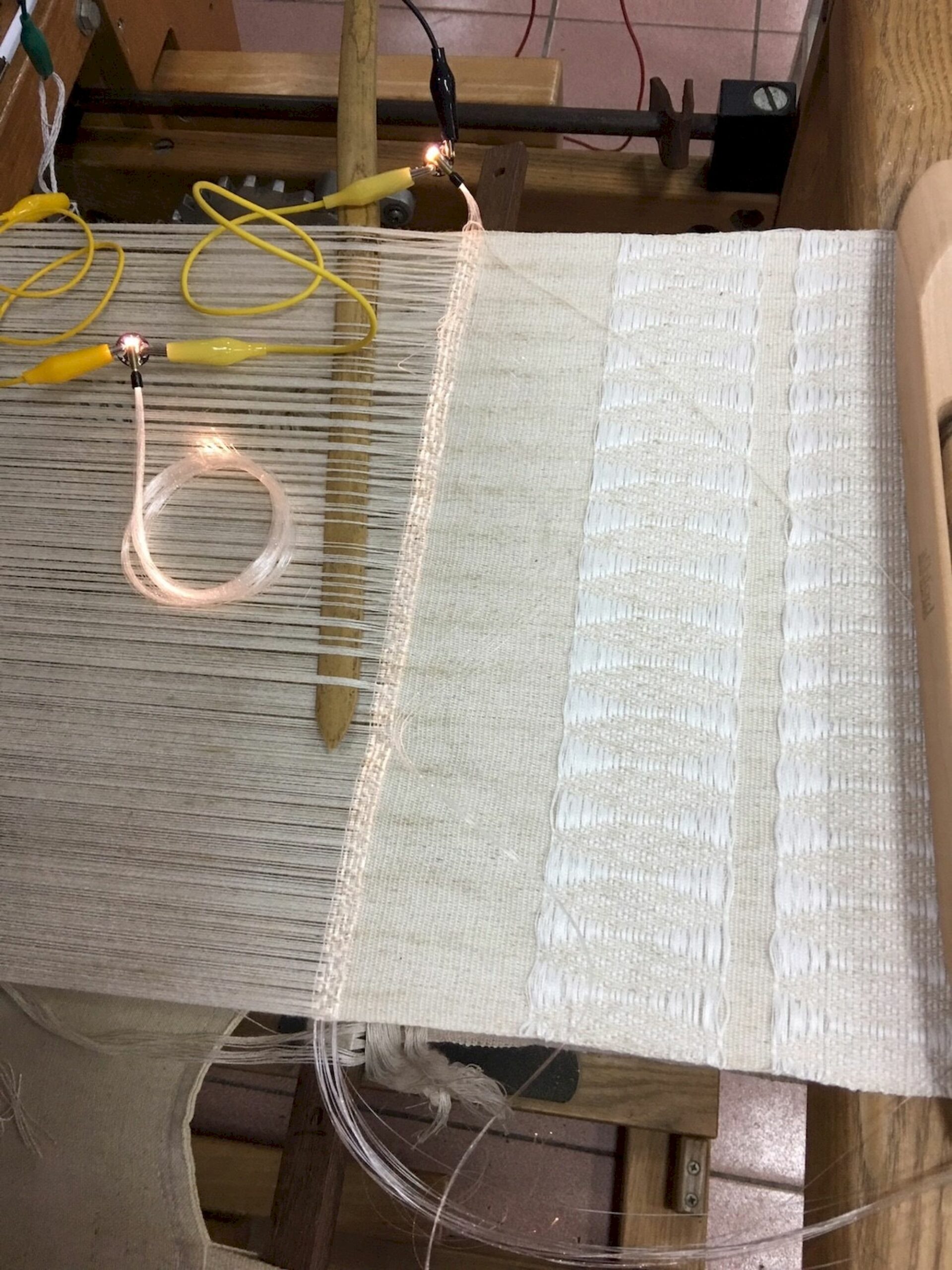

I firstly started my interest in combining traditional craftsmanship culture and modern technology in an art residency program in Oaxaca, Mexico. Before that, I had already started my interest in e-textile crafting when I found my first conductive threads on Adafruit. I was very into looking for a way to create new art by new materials, and these conductive threads represent the potential to turn all electronics to flexible textiles form. I was deeply amazed by its flexibility and conductivity. While I was having fun on the material side, I was also looking for the cultural meaning in the textile contexts at the same time. And somehow I didn’t look for it in the European system. Maybe it’s because I found everyone around me was so into the European art program so that’s why I decided to embrace a punk aesthetic.

A founding project for you was a textile residency in Oaxaca, can you tell us more about it?

I was developing a project focused on embroidering circuits using conductive threads back in 2011. This choice was motivated in part by my decision to join a residency program in Oaxaca in 2013, a town renowned for its rich textile culture. During one of my open studio days, I had the pleasure of meeting Leo and Clarissa, the creative minds behind Bandui Lab. This dynamic couple specializes in cartoon and toy design. They invited me to collaborate on their initiative, which seeks to preserve Aztec ancient culture by transforming mythology and folk traditions into wooden action figures. This experience inspires me that art projects can do much more outside of white cubes or winning art awards and give real impact to social projects. I feel like this might be the reason why I developed a nomadic habit to work while traveling with DIY tools, in-between different international art networks beyond my island home in Taiwan.

You used the Charlieplexing technique, can you tell us more about it and how you used it?

It was somewhat of a casual idea, or a slacking one. I was researching ways to minimize cross stitch and embroidery work to make my wearable project “I am Very Happy I Hope You are too”. In the process, I came across a Charlieplexing circuit online which is a method to obtain more LEDs outputs with relatively fewer I/O wires from my Attiny85. While I didn’t end up implementing Charlieplexing in those particular masks, the experience inspired me to recognize a potential correlation between the structures of electric matrices and textile patterns by the means of coded messages, as well as my interests for the history about how textile technology developed computing technologies.

You initiated the event Tribe Against Machine in Taiwan, can you tell us what were the objectives and explain what are the traditional Atayal textile?

Following my residency in Oaxaca, I took part in an e-textile summer camp hosted by Mika Satomi and Hannah Perner-Wilson at Les Moulins de Paillard in France from 2015 to 2017. This experience brought me into contact with numerous e-textile enthusiasts and brilliant minds. In 2017, intuitively, I initiated the organization of a summer camp in Taiwan, inviting these individuals and connecting them with a Atayal community called Lihang Workshop, led by Yuma Taru. I named the event “Tribe Against Machine (TAM)”, embodying a rebellious concept against commercial art and academic systems. Although we engaged in the organizing without profound academic or anthropological considerations, the event proved to be remarkably successful on a human-to-human level.

This event spanned two years and received funding from the National Culture and Arts Foundation (NCAF). The entire fund was allocated towards inviting indigenous artists, members of Lihang Workshop, and covering the 50% of all international flight tickets. I am especially grateful for the dedication of the remaining collaborators, who worked voluntarily. Special thanks go to my collaborators and friends, Foison Arts and Maker Bar in Taipei for their invaluable support during that time.

There was also a “wearable zine” project, can you explain?

This was the conceptual theme of Tribe Against Machine 2017, to provide a framework that inspired participants to generate ideas on how to contribute to cultural preservation through functional smart textile prototypes. Our discussions centered on the notion of empowering original preservation tasks by digitally reformatting them with new materials, all while respecting the traditional Atayal textile format. Moreover, the goal was to embed this new knowledge into participants’ daily practices, aiming to bridge the gap between electric engineering and traditional weaving, so to speak, similar to how I embroidered circuits with conductive threads among the Aztec villagers in Oaxaca. I considered the framing of the project to be a clever strategy that proved effective. However, when looking at the initiative from a long-term perspective, I believe consistent training in electrical engineering remains necessary and essential for the sustainability of both the event and the broader movement.

You then moved to a project of a greenhouse in Tibet, and then a project at Atacama? Seems you like exploring remote places, can you elaborate?

After organizing TAM for 2 years, we didn’t continue the project after the funding ran out. I met a Tibetan Rinpoche Tsansar Kunga in Taiwan through a friend of mine who was trying to help him to digitally scan a series of Tibetan calligraphy scripts from his passed-away father by chance. I had a chat with him at his place in Taichung and he told me he was organizing a charity orphanage school called Tashi Gatsen in Yushu county, Qinghai province for years. After this meeting I have voluntarily visited the school 3 times during 2018 trying to continue my experience to establish another camp in this community, and eventually I ended up to participate in a greenhouse project initiated by a weather engineer Wiriya Rattanasuwan to help the students from Tashi Gatsen School to grow their own vegetables instead of the expensive imported ones from other provinces of China. Because I do not have any experience building a greenhouse, I consulted Wiriya and some other friends to organize my action and the design in Qinghai. Finally we have the first prototype built in Yushu at Tsangsar Kunga’s home house, and unfortunately the project was forced to be closed right after the arrival of the pandemic in early 2019 and I have never gone back to the community again.

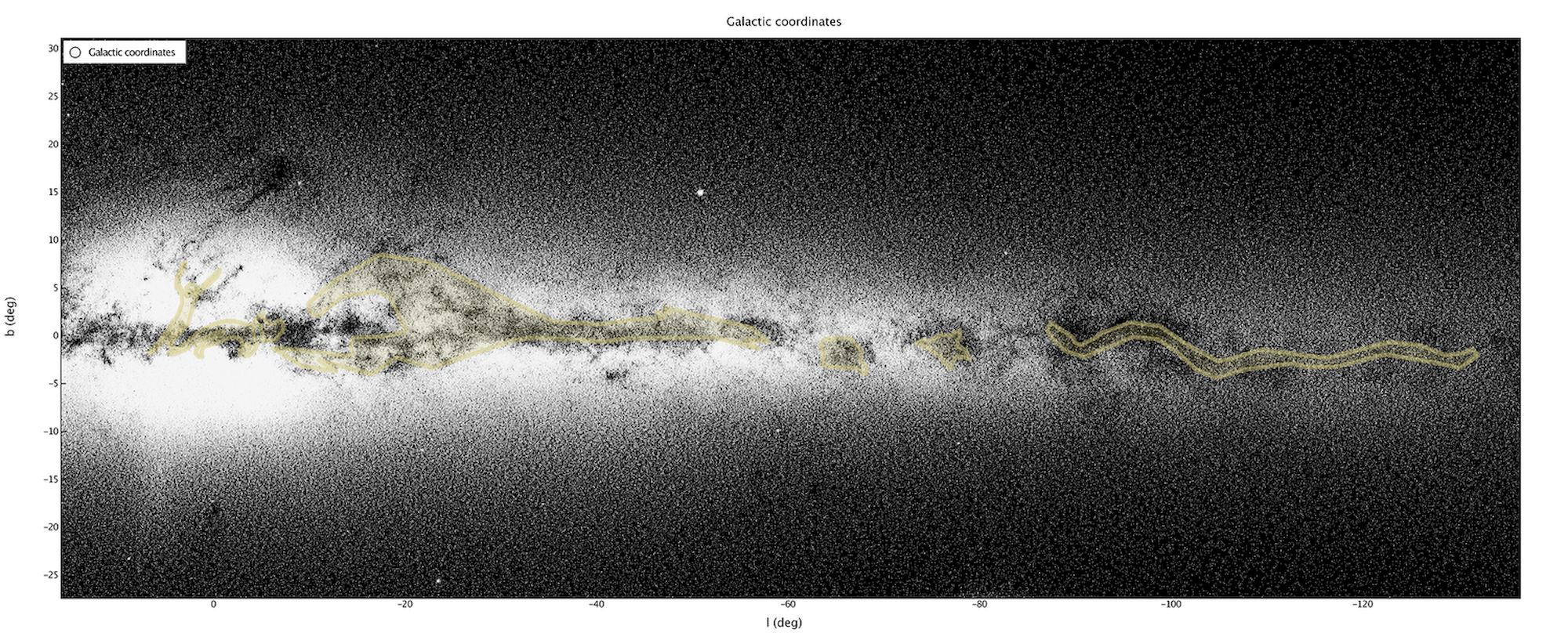

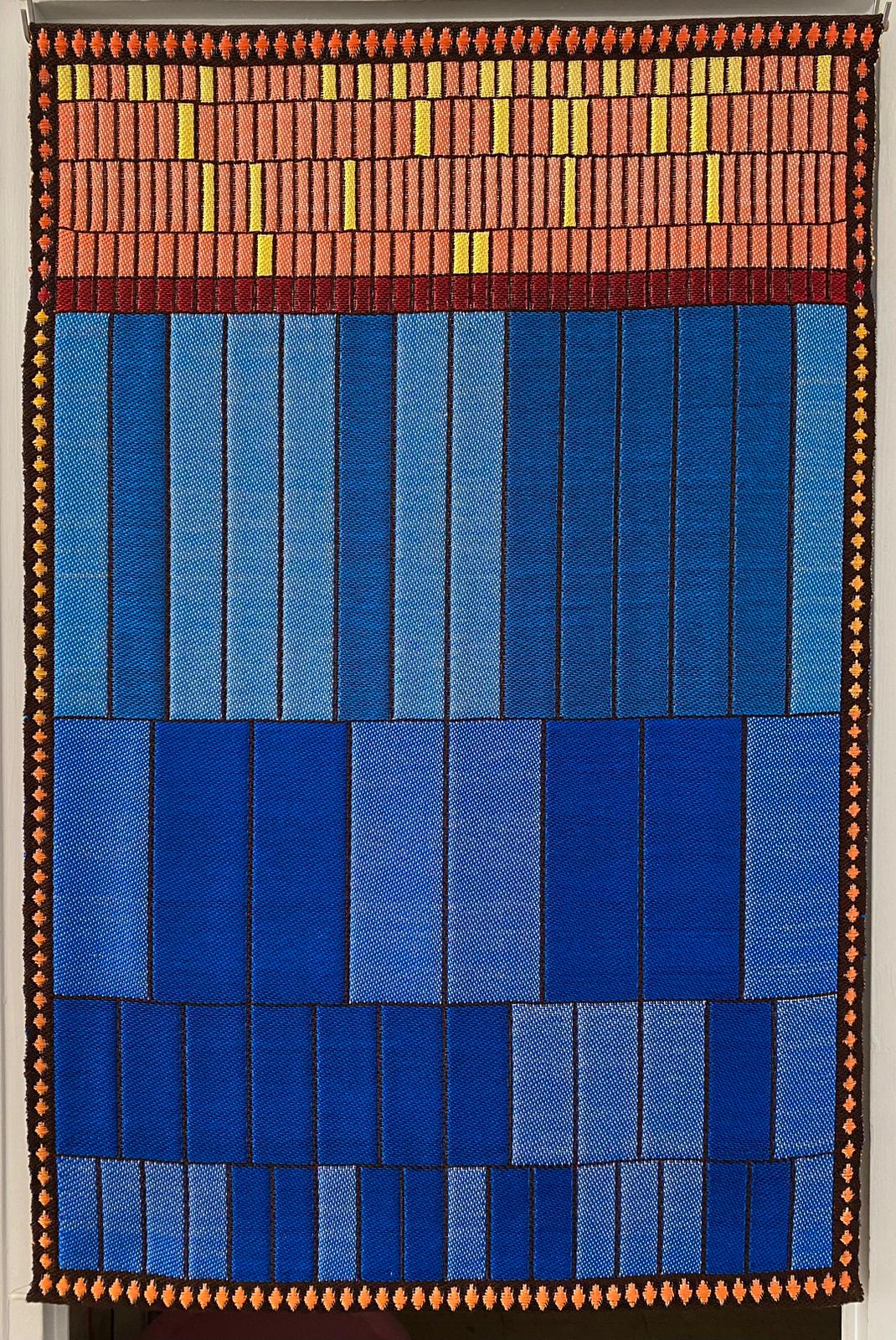

Regarding Atacama, I got an invitation from Maria Jose Rivers to join her I_C Project, funded by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). Maria had discovered me online years ago, but it wasn’t until 2021 that we finally collaborated remotely. The I_C Project is all about uplifting Andean culture and identity in Chile by bridging ancient textile traditions with modern astronomical data.

Given my limited knowledge of Andean civilization and the vast scope of research, Maria suggested I kick off my exploration with the Incas’ dark constellation. So, I dedicated some time to delve into this topic. Eventually, I crafted a system to visually represent the dark constellation culture using data sourced from the Gaia Library. I symbolically translated the Inca dark constellation’s region into intricate textile patterns.

Read the second part of this interview.

Documentation of Shih Wei Chieh’s residency at Hackteria in September-November 2023.