Fabrikarium Tokyo: prostheses and processes in the land of shower toilets

Published 23 May 2023 by Cherise Fong

My Human Kit’s inclusive makeathon to make practical solutions to everyday problems of physically disabled individuals was held for the first time in Japan on May 4-6, 2023, in partnership with Fablab Shinagawa, hosted by the Miraikan museum of the future in Tokyo.

On the 7th floor of Miraikan, the National Museum of Emerging Sciences and Innovation, the small dark auditorium bustles with turquoise T-shirts, their backs bearing the slogan of the past three days: FABRIKARIUM TYO 2023. The music begins with a gentle percussion that envelops the room, then an acoustic bass player joins in the live jam on stage, as the big screen flickers to life behind him with psychedelic images. Little by little, people raise their arms and wave them in the air, the synchronous rhythm of their movement activating small blue lamps hanging above their heads.

On the screen, a live video insert captures the activity on stage, along with the face of the artist orchestrating this virtuoso “Eye Show” extraordinaire. It’s DJ Kajiyama, whose severe muscular dystrophy doesn’t stop him from controlling music interfaces, playing video games or even flying drones from his electric wheelchair – using his left thumb, his two big toes, his cheeks and his eye movements. DJ Kajiyama is accompanied by a team of musicians and video artists, sound engineers and artificial intelligence experts.

Jonathan Ménir, president of My Human Kit in Rennes, also joins in the jam from his electric wheelchair thanks to his Magic Joystick made-in-fablab. He is one of the 15 members of My Human Kit who made the trip all the way from France to participate in the first Fabrikarium in Japan.

After three intensive days of bilingual collaboration in Japanese and French, countless hours of testing and prototypes, Eye Show was the orchestral pièce de résistance of the public presentation that concluded this Fabrikarium Tokyo 2023. Among the other objects prototyped during this inclusive makeathon: arm prostheses equipped with culinary utensils, a cherry blossom-shaped cane base, a detailed 3D-printed model of a rocket reactor for non-sighted tactile appreciation, and a portable kit to transform any toilet seat into a bidet with the press of a button.

Since the launch of My Human Kit, an association initially founded to support the project of building a myoelectric hand prosthesis for Nicolas Huchet in Rennes, France, the Fabrikarium has remained faithful to its original concept: an inclusive, open source digital fabrication workshop in which teams of ten people (engineers, designers, programmers, occupational therapists, caretakers…) come together to tackle the specific problems of differently abled individuals – also known as “Need Knowers”, who best know their own needs.

First Fabrikarium in Japan

After the first Fabrikarium held outside France, co-organized with Maker’s Asylum in India in 2018, Fabrikarium Tokyo 2023 is My Human Kit’s first Japanese collaboration, co-organized with Fablab Shinagawa. The success of the initiative is also due in large part to the charismatic energy of Sonoko Hayashi, an occupational therapist with over 20 years of experience, director of Fablab Shinagawa as well as the ICT Rehabilitation Research Group, known among other things for her colorful 3D-printed ergonomic adaptations to facilitate fine motor coordination when manipulating tools.

Her vision of rehabilitation through fablabs perfectly complements Nicolas “Bionico” Huchet’s mission to create and maintain dynamic communication between people with disabilities and people with the technical expertise to offer them practical solutions.

“I have so many ideas for inventions that I didn’t have before I was aware of everything that I could do with my disability, with one less hand,” he says. “A Need Knower might not imagine, for example, that you can eat standing up with just one hand. Because you can be standing and hold the bowl with the adaptation that was made for you and eat with your valid hand. (…) Technology alone is not enough. It’s not enough to have a solution and give it to someone, that person needs to be receptive, there needs to be a mutual understanding.”

Gadget Tools: prosthetic utensils for cooking and eating

As Nicolas Huchet’s Bionicohand continues to be improved and refined, two new Japanese projects at Fabrikarium Tokyo aimed to build utensil-specific prostheses for the kitchen.

“Ken-chan” Ono from Fukushima, whose left forearm was amputated after a work accident several years ago, dreams of resuming his 30-year vocation in the culinary industry, and even of opening his own restaurant, if only he could still cook like a pro. His team made him an adaptation for the Bionicohand that can firmly hold a large 28cm pan, with which Ken-chan was very happy to cook an omelette. While he wishes the prosthetic could be more stable, he appreciates the fact that its angle can be adjusted on three axes and is enthusiastic about improving it further.

Kouta Kawabe, 19, born without a left hand, was able to cut his own meat for the first time using an adaptation in the form of a knife. The spontaneous giggle that followed his first mouthful expressed his joyful delight in discovering gastronomic independence with his new custom-made prosthesis.

“There are so many things you can eat with a knife and fork,” he beamed at the presentation. “Now I want to eat steak, pancakes…”

Nicolas Huchet insists on actively involving such Need Knowers: “I want people whose activity is limited by their amputated hand to be aware of these alternatives that we are inventing and to be more and more involved in co-creating their solutions – because they are the ones, with their disability, who will push things forward.”

Leg It Go: all-terrain cane tips

Lisa Fujita, a Japanese student of fine arts in Nantes, France, suffers from a poliomyelitis-like syndrome since the age of four that paralyzes her legs. Currently she can walk using an orthosis and a cane, but she often slips on wet surfaces and easily trips on uneven ground. In addition to a tripod for her cane and straps to hold her crutches, her team made two cane tips that are specially adapted for sand and slippery surfaces. And because Lisa likes to stroll under the cherry blossoms in spring, their custom design integrates shapes of sakura petals, as she regains her confidence to stay active in all seasons.

Mirai Can See: “It’s not rocket science”

Kazunori Minatani was born with a severe visual deficiency, but for the past 12 years he has been researching various tactile and haptic technologies, often using 3D printers, to help visually impaired people better apprehend their environment. During Fabrikarium Tokyo at Miraikan, he wanted to make the museum’s science exhibitions more accessible to non-sighted visitors. First prototype: an intricately detailed 3D-printed model of a rocket reactor that they can manipulate in extenso with all their fingers.

Notaboo: Jérôme in Washletland

Jérôme Jankowiak, 40, was born with impaired fine motor skills, which has made him dependent on others in many aspects of his daily life. But one place where he is determined to take control of his own affairs, is in the bathroom: “When you have a disability like mine, when you can’t wipe yourself, everything that has to do with pureness, being clean, it affects your self-confidence. I want to preserve my intimacy without asking someone else for help. Because it’s every day, you can have less confidence in yourself when you know you’re not independent.”

Jérôme is fortunate to have a Japanese “shower toilet” installed in his home in Lille, but as these pricey Washlets are hardly the norm in France and in most of the world, he has long been trying to develop a portable solution.

“We’ve been on the toilet for the past ten years,” laughs Mireille, Jérôme’s mother. “I mean, for the past ten years we’ve been trying to find a solution for Jérôme, so we started out from scratch, with the little batteries you put in alarm clocks, an aquarium pump and an iron nozzle. It was pretty basic.”

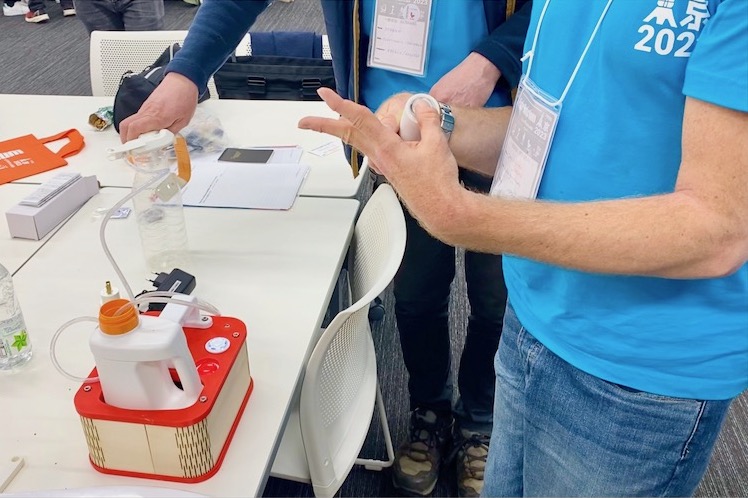

While there exist a few commercial portable devices that offer a cleansing water spray, they are difficult to manipulate by people with impaired fine motor coordination. Over the past year, Jérôme and Mireille have been collaborating with the Humanlab fabmanager Yohann Véron and an entire team of My Human Kit volunteers in Rennes. So far, they have developed a kit consisting mainly of a piece that fits under any toilet seat and delivers a water spray that is triggered by one big “remote control” button. The whole kit fits into a compact box that can easily be carried into a public bathroom stall.

And because the first step in finding a solution is being able to talk openly about the problem, Jérôme’s association is not limited by the modesty barrier, beginning with its name: Notaboo Solutions.

In Japan, Jérôme finds himself in a Washlet paradise both private and public. The Miraikan museum even commissioned a special exhibition dedicated to toilets in 2014. It’s a rare opportunity for the French members of the Notaboo team to get inspired from the multiple forms and functions of the local facilities, and for all of us to consider the significant social (not to mention sanitary) impact of these now ubiquitous shower toilets in Japan, which were first commercialized in 1982.

Le #fabrikariumtokyo2023 c'est déjà fini 😭 Nous avons vécu trois jours forts en émotions. Nous repartons en France riches de nouvelles idées, de nouvelles façons de faire et de nouvelles amitiés 🤗 ありがとうございます Arigato gozaimasu 🙏 Au plaisir de se revoir bientôt 🌸 pic.twitter.com/ouU5h8dioT

— My Human Kit (@MyHumanKit) May 7, 2023

After emerging from three days of doing-it-with-others at Miraikan, Nicolas Huchet hopes that “this dynamic exchange initiated by Fabrikarium Tokyo will continue: [people with disabilities] meeting new collaborators, discovering makers and fablabs and DIY.” Without forgetting to thoroughly document everything online: “The goal is to share, to modify and to share again for the common good of humanity.”

This kind of empowerment through individually taking charge of one’s own prosthesis or pathology using open source technologies recalls the Open Artificial Pancreas System and other patient-led projects. Or the Japanese “one-armed guitarist” Teruhiko, who at the peak of his career suffered from a stroke that left the right half of his body paralyzed; after five years of rehabilitation, he reinvented himself on stage by playing guitar using his left hand and pedals.

The Fabrikarium is also a chance for us all to project positive perceptions of disabilities, beyond barriers, among the general public, in favor of catalytic situations in which to invent together new solutions – open, adaptable, and independent.

Fabrikarium Tokyo 2023 website

Makery’s report on the STEAM Fabrikarium in Mumbai in 2018