Feral labs: interview with Stefanie Wuschitz from Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory (2/2)

Published 23 November 2020 by Ewen Chardronnet

Stefanie Wuschitz, media artist, researcher and founder of the feminist hackerspace Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory in Vienna, participated in the Feral Labs Network artist-in-residency program this fall at Schmiede festival in Hallein, Austria. Part 2 of our interview.

Stefanie Wuschitz works at the intersection of art, research and technology, with a particular focus on feminism, open source technology and peer production. In 2009, she founded the feminist hackerspace Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory in Vienna, encouraging art and technology that is developed from a female perspective. She answered our questions during her Feral Labs Network artist residency at Schmiede, Austria (read Part 1).

Makery: Who is Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory?

Stefanie Wuschitz: We are a collective of six artists who take on a feminist, new materialist perspective and post-humanist approach to technology. We try to create a safer space for hackers to explore queer feminist projects, at the intersection of art and technology. We are Taguhi Torosyan, Patricia J. Reis, Lale Rodgarkia-Dara, Ana Fernandez, Stefanie Wuschitz and more recently Barb Huber. Together we develop an annual program for exhibitions, workshops and events to be held in our space. There are also members of our community, who come to use the CNC, the 3D printer and the workspace. But we are always open for international collaborators to apply for new exchanges or shared programs. Many feminist artists or biohackers have exhibited in this space, including Mary Maggic and Hui Ye. We try to encourage people who are at risk of stopping their artistic career. We support them to keep going, to share their skills, learn, develop their work with open source technologies.

Can you tell us about your project for the Feral Labs Network residency at Schmiede?

I’m working on it with Dorothé Smit from Salzburg University’s Human Computer Interaction Department. It’s part of a bigger project, a three-year project, about diversity in makerspaces, fablabs and hackerspaces. It’s a collaboration between Happy Lab, Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory and the Austrian Institute of Technology. Together we try out different ways to make the culture emerging from these labs more inclusive. The idea of this particular project at Schmiede was to generate interactive portraits of feminist makers/artists. I was drawing all these portraits of nerds and geeks by hand, then we laser-etched them onto acrylic plates. Now the hand-drawn faces are moving on wheels and get projected on the wall behind the installation.

We also invent new feminist hackers of the future by overlapping and blending existing faces through these interactive projections. I’m working with motors that are very silent (with silent step sticks), and the installation will have sensors that react to people’s speed. I hope that in a dark space it will work really well and amplify the light effect on the wall. While these wheels are rotating and the projections are overlapping, they always merge in different ways, deconstructing and reconstructing the lines. Actually I already started to work on it during the lockdown and I wanted to show it in a different context, but that event got canceled. So now I’m showing it at Schmiede. Dorothé is conducting interviews with different participants here, so she is covering in a way the theory part, while I do the practical part.

Who are these feminist hackers, artists and activists you’re portraying?

I’ve done many portraits of feminist activists and hackers from the 1970s, and now from Indonesia in the ’60s, trying to track the history of feminist hacking and create a narrative of self-reliance. I want to show how feminist hacking is also a methodology for artistic articulation. It’s basically about making visible new role models for feminist hacking. I’m trying to build a connection between the ’60s and the ’90s and today, us here at Schmiede. Some years ago I worked on portraits of feminist hackers in New York: Carolee Schneemann, Lillian Schwartz and people who wrote software in the 1970s, who did early works with motors and kinetic art. For Schmiede, I focus on 6 particular people. For the Indonesian project, I did interviews with around 10 people.

Not many people in the West are well informed of the 1965 coup d’état and genocide in Indonesia. Can you tell us more about it and your interest in the women’s movement?

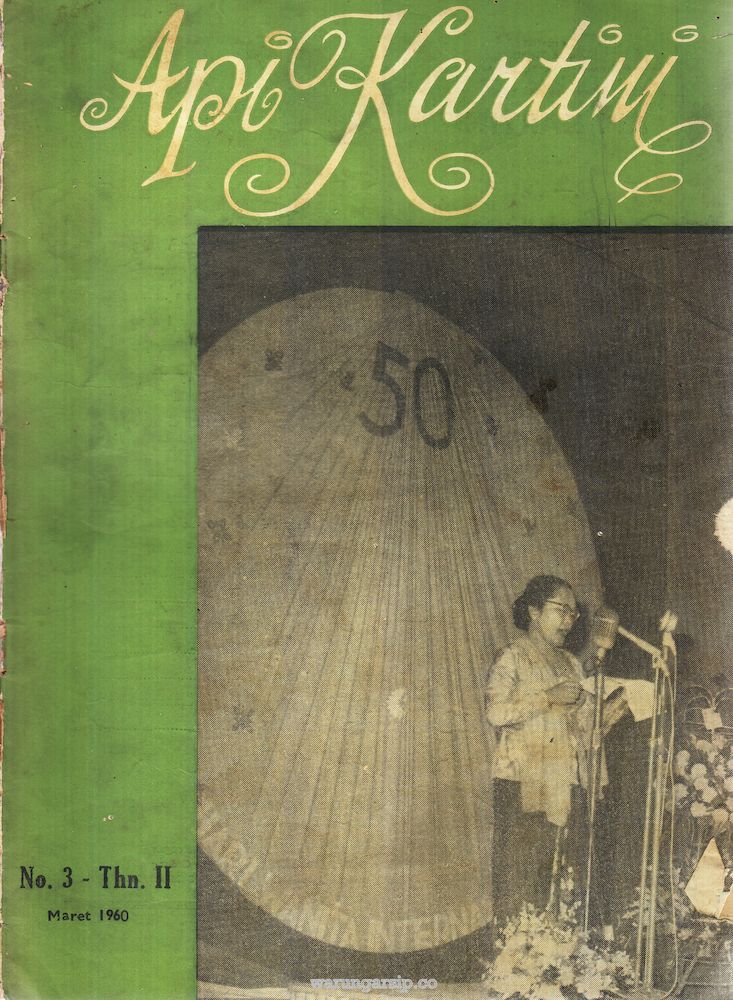

For around 300 hundred years, the islands known today as Indonesia were oppressed and exploited through colonization. Then in 1945, Sukarno declared Indonesia’s independence as a nation state. Although it was not accepted by the Dutch at first, the Japanese had occupied Indonesia, which led to a power vacuum after WWII. The independence fighters of the archipelago who had joined forces to form a nation state intended to free themselves from Western exploitation. These different groups who joined to fight against colonialism had been very different: there were military, islamic groups, socialist groups, marxist groups, nationalists of course, and they started a government that was going into a very social-democratic direction. In fact, they planed to nationalize all companies and mines—oil plants that were owned by the Netherlands, Britain, Australia, U.S., etc.—and of course, these countries didn’t like that at all. The U.S. declared that Indonesia would be too close to communism, as it was during the Cold War, after all. In fact, communist parties did not win the elections in Indonesia at that time, it was rather the nationalist party who said the industry should be in the hands of Indonesians. While the nation state was still manifesting itself, there was one feminist NGO that grew fast. It was called Gerwani (Gerakan Wanita Indonesia, “Indonesian Women’s Movement”).

Within 10 years, Gerwani grew to 2 million members. What this feminist organization was mainly demanding was free education to enhance critical thinking within the population and political positions for women, the end of polygamy, as many women were desperately trapped in polygamous wedding contracts. They wanted a reform there. Gerwani had a lot of artists among them, because of the way they organized around peer production. They established groups for puppetry, dance, theater, improvisation and music. These groups turned into channels of knowledge transfer. Among the members were many female students, but also a large proportion of farmers who fought for a land reform and visited Gerwani’s literacy workshops. There were groups asking for fair wages in sugar cane factories and visited the dance workshops. So the movement was taking a classic social-democratic turn, with many members being part of Gerwani and several workers’ unions at the same time. Unfortunately, pressure from ex-colonial powers increased. A part of the military that was collaborating with the U.S. military triggered a coup d’état.

Suharto was put into power, which marked the beginning of the New Order regime. Suharto was a kind of puppet president from the West. He stopped all the reforms and declared all self-organized groups and the feminist organizations in particular as state enemies. Within two years, most of the leading women of the feminist organization got killed, and around 1.5 million people were killed in total. It was a huge genocide. A genocide tolerated, if not enhanced, by countries who had sided with the West during the cold war. Under Suharto, Indonesia was invited to be part of United Nations and to visit the White House, and in return Nixon visited Jakarta. It was not necessarily Indonesian citizens killing each other, but there exists solid evidence that the control over those killings was centralized and executed by the military and supported by secret services from the West. Today there is proof that the U.S. delivered name lists and weapons, and that it trained generals on logistics, etc. Many members of this feminist movement went to jail for over 15 years. But even in prison, many of them were still trying to come up with a code system to hide and share information, hidden in songs, in cooking recipes, (e.g. the ingredients of certain recipes would have certain meanings). Or music bands would pretend to rehearse, while actually meeting as an activist group. Still today, the survivors of the New Order regime are stigmatized. Whole families were stigmatized, and even now, most Indonesians do not speak about these years with their relatives.

How can you reconnect with this history today?

Thousands of people had to escape Indonesia in 1965. Some went to the Netherlands, so I will also try to go there to do interviews. Many archives on Indonesian resistance are not in Indonesia but in the Netherlands. It’s still taboo in Indonesia to have been involved with these grassroots organizations, DIY groups or leftist movements. Everyone who is an activist today, who works with open hardware, skill sharing, or knowledge sharing, digital literacy or climate equality, they are all almost invisible if you go there, or if you try to visit them on site. But they really do have a big online presence: gigantic websites that look super professional. They cultivate social media interactions with the whole world, so in my opinion they use the Internet to reach out directly to international activists and audiences or an international art community. Decades of state propaganda has formed their view on the power of media. They do not reach out so much on a national level, where they are usually cautious. Many of their websites are entirely in English, they gain visibility through international festivals, exhibitions, conferences. I think it is also a strategy to overcome national oppression and restrictions.

The digital NGOs that use digital platforms today as a way to exist in the world, to manifest themselves in the world, are really informed by this history and tragedy, by that mindset. So the interviews are about that. The first step would be to admit and acknowledge that the genocide happened, as shown through evidence of international researchers such as Saskia E. Wieringa, Jess Melvin or Annie Pohlman. Since this genocide is not yet acknowledged by the Indonesian government, the second step would be to free these women from stigmatization, and the next step would be to learn from them. What did this feminist movement do right, to engage millions of members into their struggle in such a short time? So that’s what I’m trying to do with my project “Coded Feminisms in Indonesia”.

Cindy Lin Kai Ying (SG), Stefanie Wuschitz (AT), Lifepatch (ID), The Nenek Project: Why are there so many hackerspaces in Indonesia?:

How does that inspire you, in terms of the global political situation?

In those years, there was a lot of art and DIY. Activists would meet in small groups, share their knowledge, songs, theater plays, jokes, which would entail all this information and political perspectives. If they had stayed in power, it would have been amazing. For instance, they really didn’t want Indonesia to pay back the debt from colonial times, which is still a topic today, right, paying back to the West. They said all oil companies should be owned by Indonesian companies, while now 80% of the companies are owned by British, Australians, Japanese, Americans, and there’s so much oil. The gold, the copper, the palm oil profits mostly go to international corporations. If they had found their way, we wouldn’t have the problem of climate change now, since they are burning down all the jungle there, which is equivalent to the lungs of the Earth. The forests in Indonesia are burned down—what they do now is much worse than what colonizers ever did. Once a year, all Singapore is in smoke, smoke clouds so large that you can see them on satellite images. People cannot breathe outside during these yearly peaks of forest fires. This is also one of the reasons why we have Covid-19 now. They destroy forest regions where animals never had contact with human civilization before. If these animals end up on the market as food, we know now what it means in terms of virus mutations.

The digital commons activists I know in Indonesia try to keep Coca-Cola and Nestlé from buying up the only water source they have in their city and prevent it from being privatized. They don’t have water during the day, they collect water during the night with big bins. The activists collect trash such as old car wheels, and try to keep the mountain area clean in order to keep the water clean. Otherwise a bottle of water costs like 2 euros (equivalent to 20 euros here) and there is no other way to get clean water. So the friends organized around these issues, created a digital collective to face these extreme climate problems, caused by this harmful privatization of resources.

How has the Coronavirus crisis impacted your project?

This year, I wanted to go to Indonesia to do more interviews, but as this was impossible, I asked a collaborator in Yogyakarta (Nilu Ignatia) to do the interviews. It was much better this way, because she speaks Indonesian, Javanese and the local dialects fluently. The interviewees told her many secrets that they would not have shared with me, being white and a foreigner. These interviews will feed into an animation film, that has to be done in December 2020.

This animation will be published as the outcome of my artistic research project “Coded Feminisms in Indonesia” funded by the TU Berlin where I’m currently employed as a Post-Doc through the “Digital Programm”.

References:

• Saskia E. Wieringa (1993) Two Indonesian women’s organizations: Gerwani and the PKK, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 25:2, 17-30, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.1993.10416112.

• Saskia E. Wieringa & Nursyahbani Katjasungkana, Propaganda and the Genocide in Indonesia: Imagined Evil, Routledge, June 2020.

• Annie Pohlman, Women, Sexual Violence and the Indonesian Killings of 1965-66, Routledge, 2017.

• Devi Asmarani, “Fighting the colony: Women activism beyond suffrage”, 03/18.

• David Mozingo, Chinese Policy Towards Indonesia 1949 – 1967, Cornell University, p.225, 1976.

• Journal (2015) Lentera. Salatiga, Kota Mera, Wadah Diskursus Sivitas Fiskom UKSW, Nr. 3/2015, Salatiga.

• Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, page 133, 1983.

• Gerwani on TribuneNews Wiki.

• Julia I. Suryakusuma, State Ibuism: The Social Construction of Womanhood in the Indonesian New Order, Institute of Social Studies, Depok, 1988.

• Saskia Wieringa, Jess Melvin and Annie Pohlman, The International People’s Tribunal for 1965 and the Indonesian Genocide, 2019.

• Jess Melvin, The Army and the Indonesian Genocide: Mechanics of Mass Murder, 2018.

Read Part 1 of Stefanie Wuschitz‘s interview and learn more about Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory

Stefanie Wuschitz was Feral artist-in-residency at Schmiede as part of the Feral Labs Network‘s activities, a project co-funded by the European Union’s Creative Europe program