The Bat That Therefore I am – Exploring The Eye of the Other

Published 18 November 2020 by Rob La Frenais

The Rencontres Internationales Monde-s Multiple-s, formerly Rencontres Bandits-Mages, was to be held in Bourges from November 13 to December 6, 2020. But the lockdown has decided otherwise and the festival switches online. Makery joins the exhibition of the EMAP network, European Media Art Platform, and presents the different projects that were to be exhibited in Bourges. Interview with Daniela Mitterberger & Tiziano Derme on their work with bats.

Vienna and Zürich based media artists and architects Daniela Mitterberger and Tiziano Derme are the co-founders and directors of MAEID / Büro für Architektur und transmediale Kunst, an interdisciplinary design studio created to critically locate new technologies within novel human-animal-machine entanglements. Their work strives to establish particular relationships with otherness, and new dynamics of exchange between listeners and receivers.

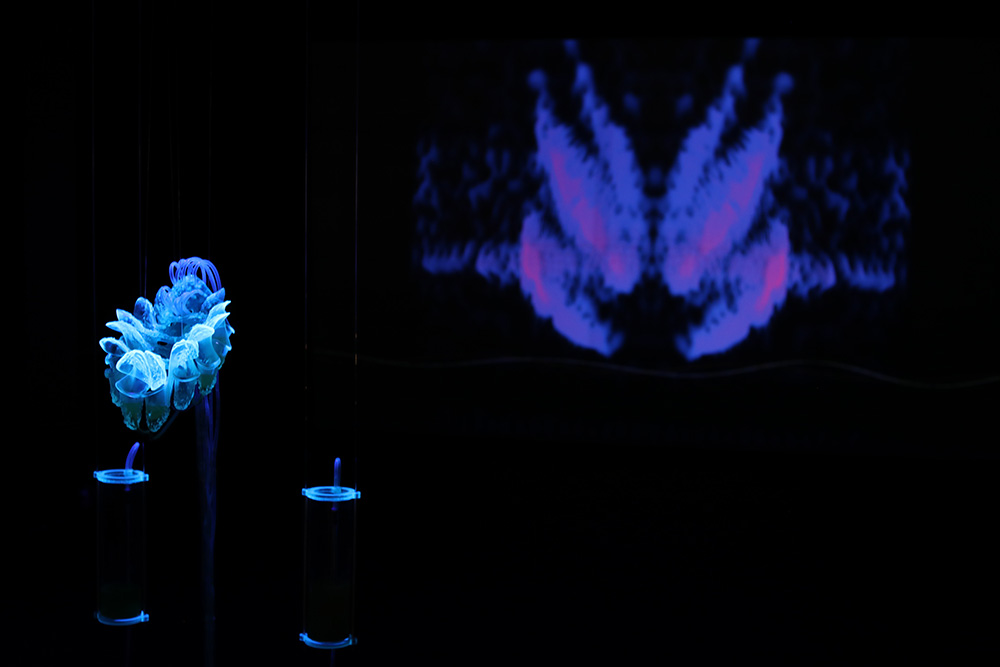

In Bourges, where they spent their EMARE artists-in-residency time in 2019 (European Media Art Residency), they were preparing the ‘The Eye of the Other’, a project that explores non-verbal communication between humans and bats, through the study and the translation of the bat’s sensorial systems. The work translates the nectar bats’ perceptual world into perceptual patterns a human can understand – from echolocation to our senses such as hearing, seeing and touching.

Daniela Mitterberger & Tiziano Derme, ‘The Eye of the Other’, teaser (2020):

Makery: The ‘Eye of the Other’ is a project about a specific kind of bat, a nectar-feeding bat. Your project, realised with scientist Ralph Simon, is about how we can understand the patterns of echolocation this bat uses. You have said that we can’t fully understand the way this bat recognises locations and communicates to other bats. Can you explain further?

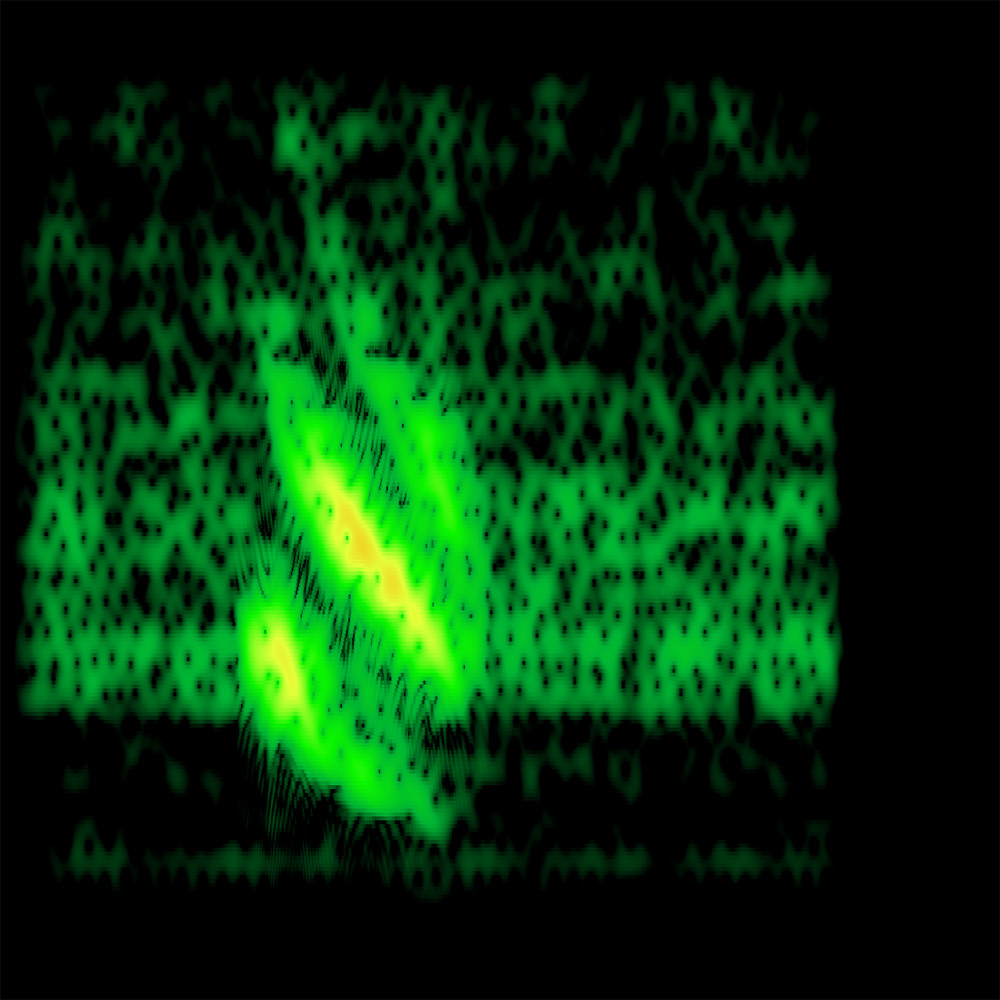

Daniela Mitterberger & Tiziano Derme: Academia, industry and science show recently an increased interest in information acquisition of natural systems. For this reason we can perceive an emergence of fields such as “sensory ecology”, which study how organisms acquire and respond to information about their environment. A striking example of such a sensory system is the echolocation of bats. Among all the numerous species of bats (1250 described bat species) most of them use echolocation (approx. 1000) for spatial orientation and foraging. Currently scientists can fairly understand, monitor or measure the very basic behaviours and multimodal perception systems, and member to member communication of bats. Nectar-feeding bats for example have a unique system of sensory compensation, that allow them to forage in cluttered situations such as rain forests to find the tiniest flowers. They simultaneously use multiple senses (vision, smell, sonar) to piece together the necessary information for the classification and localisation of these specific flowers. Low intensity calls, so-called ‘whispers’, can be seen as a particular kind of adaptation to foraging in cluttered situations, as the use of loud echolocation calls within the vegetation could result in many loud echoes masking important information about the main targets.

It seems to be the issue here is similar to the ‘Hard Problem’ in consciousness research, where we can’t actually prove there is data for the neural correlates for human cognition of ‘qualia’ like color or smell. My red may not be the same as your red. How can artists help science take a new approach here?

It is already very difficult to answer this question if we refer to Human-Human interactions as it clearly also refers to the mind-body problem. We do not understand the complexity of understanding, therefore human-animal interactions can be quite problematic because quoting Lacan – animals don’t answer questions. ‘The Other’ is in this sense a limit, the outermost edge of the human, a figure problematized by Jacques Derrida’s The Animal that Therefore I am (2008) and Giorgio Agamben’s The Open: Man and Animal (2004). But ‘human’ and ‘animal’ are flexible concepts, able to connote the social as well as the biological. Working with animals certainly presuppose the acceptance of specific facts about animal phenomenology and at the same time the acceptance to never “truly” understand what it means to be this animal, as we can not take over a first person perspective of being a bat. Therefore working within an interspecies interaction requires the acceptance of unknown facts. Quoting Thomas Nagel “There is something that is like to be a bat,” perfectly describes this condition, even if we get the perfect situation to characterize the animal behavior, we will still miss what it is like to be, as it is not about mimicking to have wings, hanging upside down or echolocate to hunt. Within this condition, any attempt of reducing this interaction to something familiar is doomed to miss the importance of an extended thinking experience. The bat’s physical presence and the sensory system are so different to us that we can never truly ‘understand’ or perceive what the bat sees. The only point we can reach is a possible understanding of how we can communicate with the truly other – which language do they understand? Is there an alphabet we could develop that helps us to create a terrain of communication? Somehow turning back the question to the project, it is all a question of “gazing”, a juxtaposition of different perspectives and modalities of communication.

We have a long experience of collaborating with scientists, so we can try to answer but it is quite challenging to speak in general terms, every collaboration is different and exists in a specific condition. Although, we believe artists can allow scientists to reframe their thinking, appreciate and understand what they are talking about. We come certainly from a tangential perspective exploring areas scientists would not dare to and multiple ‘what if’ scenarios. The field of empathy and emotion does not really have space within the realm of science, very much in the sense of ‘what you can not name, can not exist’. We believe that there is a lot of information that gets lost as we are not able to describe it yet, or we don’t have a terminology yet. At the same time, science is not an objective field (as already described by Arendt) but very much guided by human-centered questions, leading to results that are by themselves predictable. Art can help to redefine questions in a more open field, as it questions the question in itself.

You have said similar technologies learnt from bat behaviour and their echo-sounding influence research into technologies like self-driving cars. Can you expand?

Biosonar-inspired Technology represents an entire field of research that develops technical devices based on sonar systems found in nature. Biological information about biosonar systems is mainly distributed along biological models systems (dolphins, versus bats) and a plethora of sub-disciplines spanning from Behavioral Ecology to neuroscience. In Engineering and Robotics areas such as sonar biomedical ultrasound imaging represent a great potential for developing new sonar technologies, however there is still an important difficulty of transferring insights between biology and engineering. Factors such as energy, locomotion, information processing in biological systems tend to be nonlinear phenomena and continuously evolving within species. Biosonar technologies are found in nature in mainly two groups of animals: Bats and moths use an in-air biosonar whereas whales and dolphins use underwater biosonar. Bats, by themselves, are considered as top-level order within mammals, due to their highly ecological and evolutionary success. The study of their biosonar system specifically, is currently making crucial advancements for technologies applied to radar and computer vision devices. Those applications use sonar to facilitate and interpret representation of three dimensional geometry in the output signal (computer vision). Self-driving cars are currently using sonar technologies to manoeuvre the vehicles in case of fog detection, and low visibility situations. Furthermore, because the sound propagates across different media, the use of sonar is still the best technology to interpret special environmental circumstances.

You speak of a ‘subtle domain’ between the way in which artists and scientists can interpret the bat frequencies from a human perspective. Can you describe this domain a bit more?

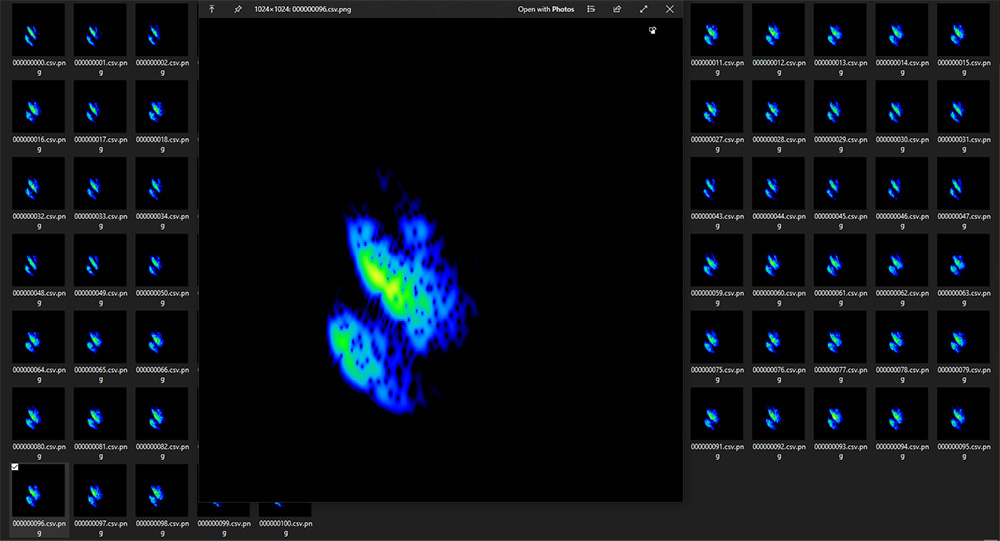

We consider this question as an extension of what we described before regarding the ‘Hard Problem‘. In the project we give a particular emphasis to the translation of the bats’ gaze / echolocation into other media. The concept of gaze is not something you have or use. Rather, it is the relationship that you enter with someone. Rooted in the project there is the deep desire to recognize the aesthetic dimension of the non-human and at the same time–sensitise ourselves, to this richer and larger bigger world made of sounds and impulses. If we try to enter in the animals’ domain without having the possibility to have the animals’ first perspective and without the desire to establish a hierarchy then you realise that you always need a third domain characterising this co-presence. This domain, between you and the animal, is a domain of reference; necessary to translate, modulate, down-sample signals from the human to the bat and vice versa. We found this domain within technology, with different devices and interfaces that helped to negotiate our presence and present the animal sensoria to the human. Agamben for example in ‘The Open’ is giving a quite intriguing image that envisions the ultimate annihilation of the human and the consequent disappearance of human language, and that we must consider its substitution by mimetic or sonic signals comparable to the language of bees. We imagine that this domain could be a mediated condition for a completely new cultural space, previewing a possible future in which the borders of humans and others are blurred and a multi-species society might be formed.

You have worked in the field both in the wild and in zoos with bats. What have you learned from this fieldwork?

For now we didn’t not have the chance to observe these bats in their natural habitat but only in the captive environment of the Vienna Zoo – one of the few places in Europe where it is currently possible to observe a colony of Nectar-Feeding bats. Doing fieldwork allowed us to realise the relational fragility of working with animals. Standing within the bat environment was quite an fantastic experience, being surrounded by those very fast whisperers can truly help us to realise and overcome many of our anthropocentric views of the world. When we stand in such close proximity with those animals, we immediately enter in a strange resonance between ourselves and the animal. This experience is especially unique when it is mediated with the use of tools and equipment that help us enrich our understanding of the animal’s environment. Within this space we lose our individuality, we do not count as species but as agents placed in resonance within the environment. Perhaps these types of experiences are a direct invitation to question our position as species among many on earth, what Latour would define as ‘terrestrials’ or earth-bound. There is also another very interesting aspect of the field work especially related to working with species that cannot be easily and directed studied. Often, scientists base their models of predictions, – measurements and analysis on a simulated representation of the animal sensoria bringing the field to the lab. When we first met Dr. Ralph Simon we had the chance to experience the animal sensoria through biosonar able to simulate and analyze real time the animal’s impulses. We realised that basically those two different methodologies cannot be separated but rather start to become part of one large mediated field between us and the animal.

You created a ‘tropical forest’ in Bourges in which you were hoping to co-exist with the bats. Can you describe the conditions you created? I understand you wanted to actually live there with the bats.

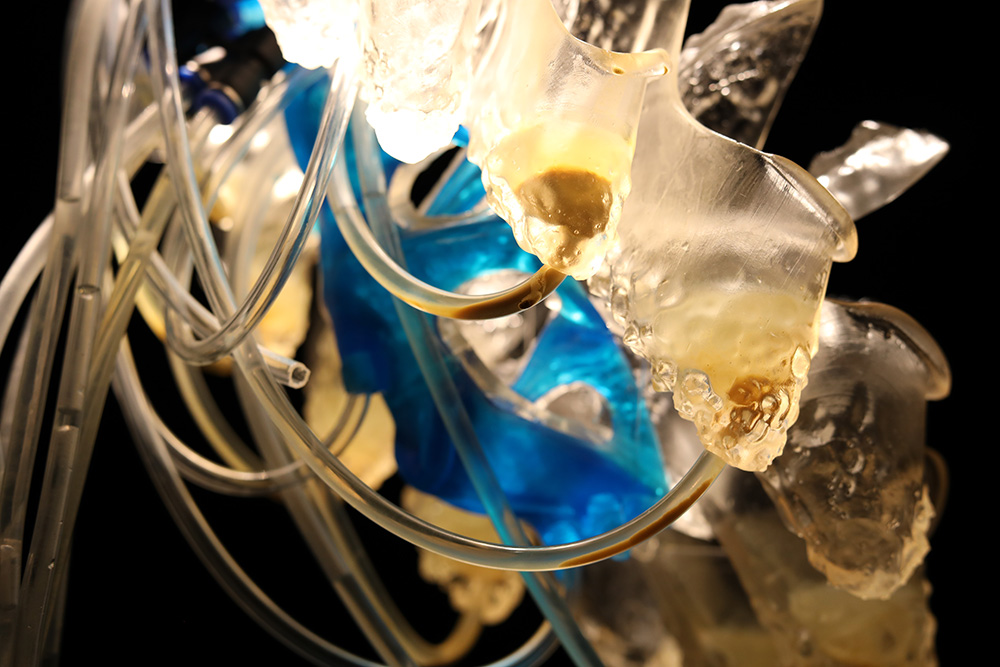

The main idea behind the exhibition in Bourges was to dissolve architecturally the image of the cage by creating an indoor habitat and allow the bats to stay. This decision included a series of actions necessary to let the bats adapt to required temperatures instead of the other way around. Temperature and humidity of the entire room hosting the artwork was regulated and adapted to the artificial environment. ‘Glossophaga Soricina’ is a species very sensitive to UV rays therefore we used an IR-red light system. Because bats are nocturnal animals a regime of inverted photoperiod was installed. Those light cycles allowed the exhibition to be carried out during their active period (day for the researcher, night for the bat). For this purpose a combination of blue and IR red bulbs work well to simulate moonlight. When maintaining bats under natural light/dark cycles, timers were set so lights come one hour after the sunrise and go off before sunset. In this way light changes were gradual and favorable to the animal’s habitat. For the species Glossophaga Soricina South and Central American bat, ambient temperature and relative humidity should be: 27-30 C, 70-90%. To provide the bat with an appropriate temperature and humidity, the main air flow of the room will be set to a constant temperature and a stand alone humidifier placed within the room . Cool and roosting retreats will be also provided. During evening hours red-coloured light bulbs will be employed to provide bats nocturnal light conditions. Specifically 4 bulbs of 150W each will be placed on the ceiling of the enclosure. No heating devices will be placed within the enclosure so as to prevent accidental burns. The enclosure for the Glossophaga Soricina was designed as a “ walk-in” habitat to favour maintenance and cleaning operations allowing the individuals bats to fly and exercise, stretch their wings, forage nectar from the artificially produced flowers in the enclosure. The size of the enclosure is measured for n.5/7 bats with the following proportions : 3.40 x 3.50 x 3.0 (w x l x h) (m) for an overall volume of 35.7 m3 . The enclosure will be made out of PVC transparent polyethylene and will have a controlled air-flow . A polyethylene mesh will be placed to allow an easy and continuous air extraction and daily cleaning operations. To provide bat places to hide and roosts a series of plants was placed within the enclosure. Those plants should not have hard branches nor blooming. Specifically the following species were chosen: Ficus benjamina, Bromeliads, Philodendron undulatum, Monstera.

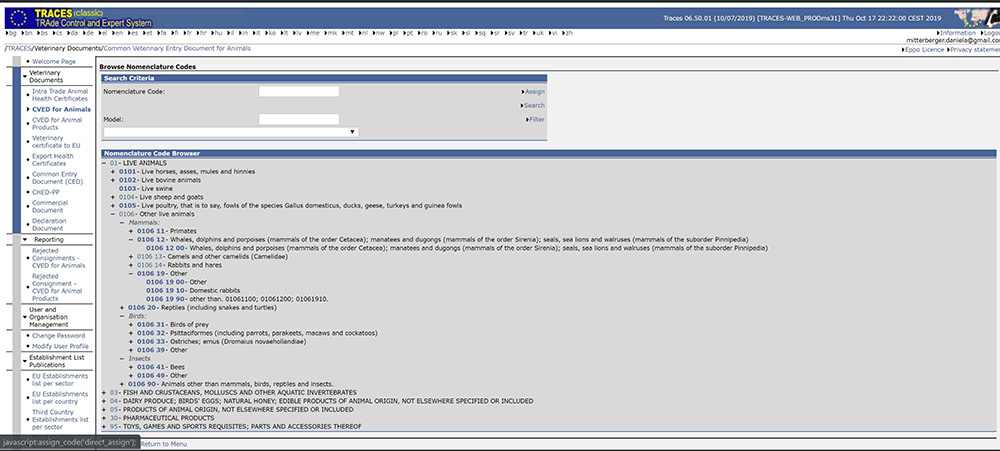

Ironically, your title reflected some of the bureaucracy you encountered when it came to transporting bats across borders to your installation in Bourges, in terms of categorising the bats on the paperwork needed, where the bats were termed as “Other Other Other’ in the certificate.

In Europe, when working with animals and transporting them from one country to another you have to apply to a TRACES (Trade Control and Expert System). This allows you to transport an animal from one research facility to the next. This also implies that the facilities need to be registered as either research facilities, zoos, universities or animal shelters. The whole route of the animals is traced and two veterinarians are needed for picking up, checking and handling the animals. In our case Bourges was registered as a research facility, the artists (in this case Tiziano) and a scientist became a private animal transporter and Daniela the organizer of the animal transport. Along the process, we were never able to mention that the purpose and reason for the transport to Bourges was an exhibition space, this would have ended all transport permissions immediately as it falls neither into amusement (zoos) nor research (universities). Currently there is no category for exhibition or art and research in TRACES hence, permissions to exhibit animals into an art environment are quite hard to obtain. Other artists hire animal trainers with tame animals to assist their exhibition as they organise all certificates. In the case of a University being the official and main registration place we had to consider practically exporting the animal across two countries, Germany and France. France is a very centralised bureaucratic country (which means if it happens in Paris it is easier to get a permission than in Bourges as you cross different zones of permission). As a route we picked the train from Berlin (Germany) to Bourges (France), 1313 Km distance. “Considering the duration of the travel 12:34 hrs, to ensure the quality of the journey for the animals, the travel time will be interrupted/broken by very minimal stops. During those stops animals will be fed and drinking water provided according to standard procedure for handling operations. The journey will be carried out in the Summer season (end August/September) to ensure optimal weather and seasonal conditions along the transport.”

Time plan for the journey: A scientist would have been present along the journey and would have accompanied the animal’s delivery. The time plan would have been carried out minimising stress and injuries to the animals. This would have been achieved by knowing the behaviour of the species being shipped and by taking the time to construct appropriate travel containers. The travel would have therefore adhere to the following ‘travel considerations’ :

“Travel at an appropriate time of the year. Nectar-feeding bats may undergo less stress if they travel at temperatures corresponding to their thermal preference (25/30 °C) Delays during the travel operations may be avoided by checking long-range forecasts for all stops along the shipping route. Travel only during working hours. Government officials worldwide generally do not work on weekends or holidays. When shipping, inform colleagues and scientific staff along the shipping route. In case of problems they can lend assistance. Plan the shipment around the ‘bat ́s feeding time’ making sure to feed the bats just prior to shipping.”

During the trip we would have provided the necessary requirements such as food and/or water. This needs to be considered just for traveling periods above 12hrs: “Prepare an appropriate style of shipping carriage for the species. A specific container may be large enough to allow bats to avoid movement and small enough to prevent injuries by limiting their movement appropriately. Flying bat containers: For short distances travels, the bats may be placed in a polyethylene mesh enclosure (which must be constructed) similar to the one used for dogs or cats within a styrofoam cooler. Containers used to travel will be large enough to allow the animals to extend its wings fully.”

Did you address the issue of ethics when working creatively with these animals? Did you encounter any opposition from animal rights groups?

The fear of animal rights groups surrounded the project, not necessarily us but whenever we were interested in collaborating with research facilities. Scientific museum directors were scared to be associated with the project purely out of the idea that the project might be misunderstood. We were never scared of that – but we took it as an opportunity to discuss the project and our position and relationship with animals. The bats we wanted to work with were not a rare species and were bred in captivity. The colony was already used to being surrounded by humans. The environment we built for them was substantially better than their concrete university cages. As the animals didn’t need to produce anything for us (build nests, hills or anything alike) we didn’t feel we treated them ethically wrong. While working with animals things are neither good or bad, black or white but rather understood with different gradients of reasoning. A good example for this is the zoo, a place popularly associated with caging of animals. At the same time zoos are places, (probably the only ones), where humans and animals spend most of their day together. Zookeepers were one of the first ones (way before academia acknowledged it) that discovered that animals have feelings, are bored and suffer. The acceptance of the existence of animal’s feelings was a notion accepted by the scientific community only recently, due to the academic fear of anthropomorphism. We would say that any creative work with animals exists on an unstable terrain, as it refers to an unchartered territory. We do not know what it means, and the only way to discover it is to experience it, on an emotional level, through exhibitions, art and science projects, as you might only get to know someone by spending time with them, with an open mind. At the same time, we continuously reflect on ourselves and the situation we create with the animals, self-reflection and criticism as an ultimate mode of production. Some artists’ friends and curators even mentioned that we might never need the bat, that the missing of the bat and a therefore imagining of the species might be even stronger than showing the animal. Again – we will only know when trying it, reflecting on it, being critical to our own work.

How would you compare your work with, say, Tomas Saraceno’s work with spiders?

We really appreciate the work of Tomas Saraceno , and somehow we believe the two projects share some crucial common interests but very different intent. In both projects and with both spiders and bats you are exposed to an animal we associate with a certain feeling of discomfort and fear. Their presence in our daily life is still quite problematic. We believe also both projects have quite intense and accurate research about animal behaviour. Saraceno’s work to our eyes doesn’t want to present to the visitor the sensoria apparatus of the animal rather the labor and performative aspect of it, while ‘The Eye of the Other’ mainly aims to give the audience cues to understand the animal sensoria in our own terms – it is a multi-modal act that develops across time and different media (sound, visual, olfactory). In this case the two projects are similar, and both trying to create an aesthetic dimension of the otherness.

When working experimentally with these bats in the field, you talk of systems of ‘reward’. How can you define these systems as humans working in a non-human world?

How can we avoid instrumentalizing animals during an interspecies communication experience? or how to avoid creating mechanisms of control over them? Those were our first questions while thinking on how to approach the project. Pleasure from positive social interactions is widely considered a driving force for human and animal behaviour. Generally positive interactions are extremely beneficial for human and non-human life. Establishing a system of rewarding is quite important for a successful interaction, those constructs firstly help to establish a ground for well-being and pleasure, second they are motivational towards the acceptance of a new stimuli, and third they help the creations of positive memory cues within the experience of the animal. Within the project for example we used specifically a layered system of rewarding based on food, smell, geometry with the aim only to stimulate the animals’ curiosity. However mechanisms for example of liking, learning, wanting are all based on rewarding mechanisms, we know it works for humans but also concerns animals. At the same time, we are also trying with other projects to investigate mechanisms of interaction not entirely based on reward. Those basically rely on establishing for example an interaction based on some sort of homeostasis between two species. Two species sharing the same environment and entering into a silent conversation not based on the enhancement and production of a particular event but rather just coexistence.

The installation in Bourges was not fully realised, as the bats could not get there in time from Berlin, because of the difficulty of getting permissions. Tell us something about the last-minute complications.

The days before the opening we were sitting on needles. We were continuously on the phone trying to contact the different responsible people. No-one was ever really responsible for us, therefore this was a sensitive act. We started to pre-heat the space to reach the desired temperature when the bats arrive. We got the permission on the morning of the opening. This meant we could not reach Bourges on time to place the bats quietly into their environment. It felt like the day of the approval on the French site was not a coincidence, as they knew they could not forbid us to bring the animals (as we had all the paperwork). We would have never pushed to bring the bats just for the sake of the exhibition, as we did not want to risk to distress the animals in any way.

How will you finally carry out this very interesting project, when you have overcome all the obstacles?

Ideally we find a location to exhibit which has already experience in exhibiting animals and can help to disentangle the bureaucratic struggle (as interesting as it is). Ideally it is a room filled with our artificial flowers, a tropical zone. We would need to spend some time with them, actually sharing the space. Ideally there should be no barrier between the animals and the visitors, allowing them to share the same space (of course including all security measurements). Until this perfect set-up we will collaborate with the zoo in Vienna and carry our artificial flowers into the cage of the bats, trying to establish communication.

More on Daniela Mitterberger & Tiziano Derme and the Büro für Architektur und transmediale Kunst.

Daniela Mitterberger & Tiziano Derme’s ‘The Eye of the Other’ at Rencontres Internationales Monde-s Multiple-s.