Crash: How the counterculture collided with Arts Lab culture in the 60s

Published 3 November 2020 by Rob La Frenais

In the last years of the ’60s and the beginning of the 70’s two extraordinary experiments happening in London, the Drury Lane Arts Lab and the New London Arts Lab are the subject of a new book, just out, written by one of the survivors of these experiments, David Curtis – ‘London’s Arts Labs and the 60’s Avant-Garde’.

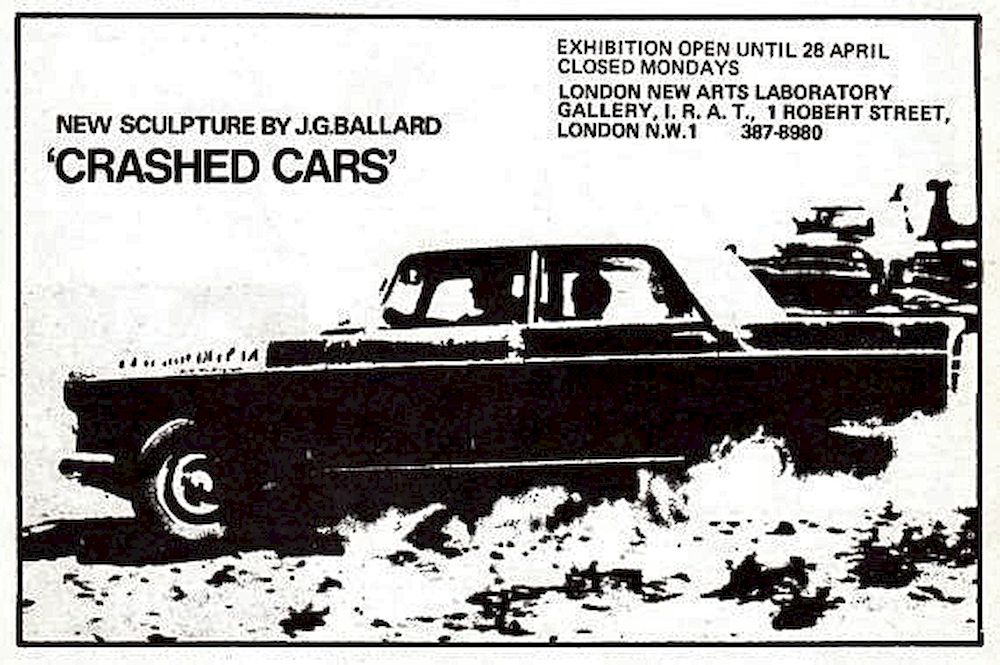

In the last years of the ’60s and the beginning of the 70’s two extraordinary experiments happening in London, the Drury Lane Arts Lab, founded in 1967 by Jim Haynes, still living and active in Paris and the New London Arts Lab, otherwise known as the Institute of Research in Art and Technology, (1969-71) where early video and computer art was initiated and J. G. Ballard staged his famous ‘Crashed Cars’ exhibition, later to become the David Cronenberg movie ‘Crash’, are the subject of a new book, just out, written by one of the survivors of these experiments, David Curtis – ‘London’s Arts Labs and the 60’s Avant-Garde’.

The Art Labs movement

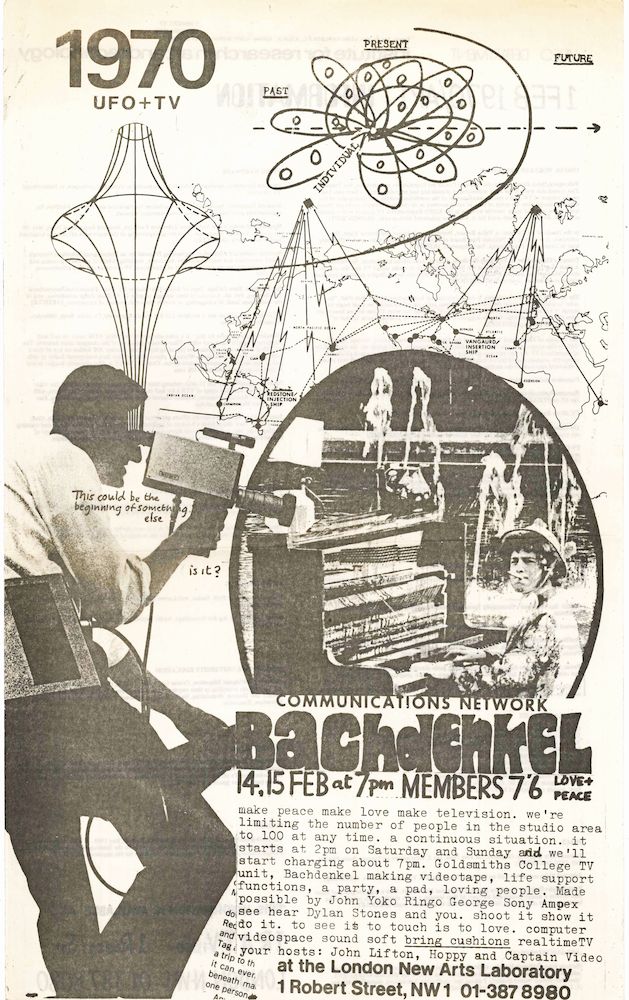

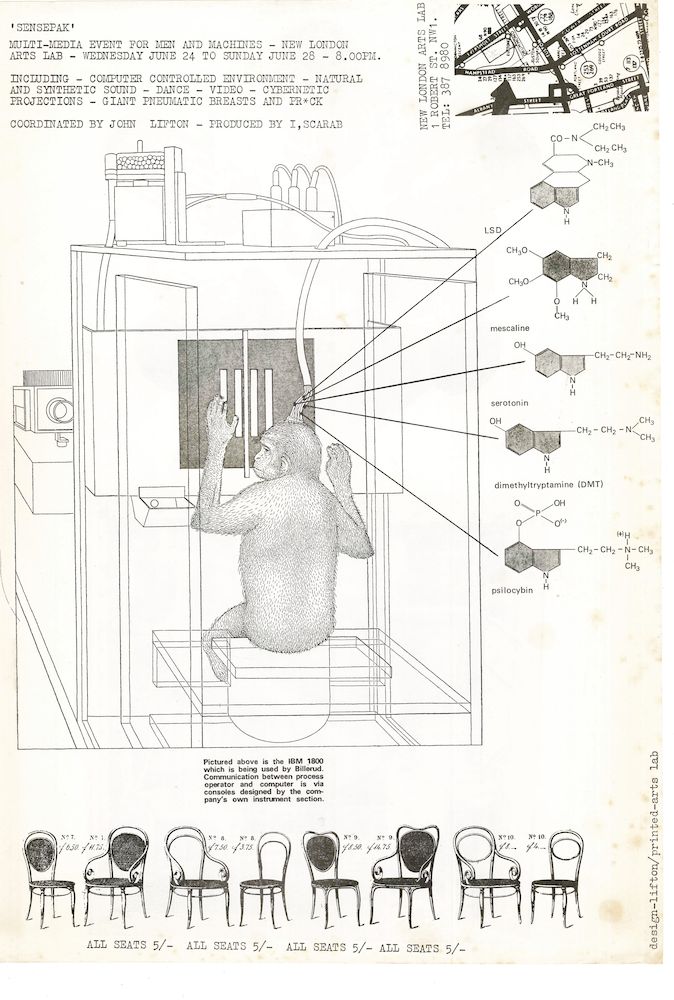

It tells an intimate and personal account of that key period in the late ‘60s and is long overdue. It is quite amazing this era has not been documented before. I asked Curtis, who was the experimental film programmer, what lessons we could draw today from the Labs. “Well, video in the late 60s was imbued with very much the technological optimism that later characterised early responses to the web. Hoppy (the founder of DIY television, TVX, which emerged from the New London Arts Lab), certainly came to see video as a medium for social change, protest and ‘liberation’”. Was there also computer art in the Labs? “One needed a lot of patience and a good dose of imagination when computers entered the frame… I remember being bored witless by computer’s spewing out random words. I remember Malcolm Le Grice (experimental film-maker still working today) showing me a prototype ‘mouse’, marvelling, and thinking at the same time that will never catch on.” This was a time of extraordinary techno-optimism, occurring as it did at the same time as Jasia Reichhardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity at London’s ICA. It occurs to me that, although there were many influences on todays art, science technology and DIY scene, such as the US EAT (Experimental Art and Technology) at Bell Labs, the short-lived Arts Labs movement provides a key genealogy, with DIY video and experimental film leading directly to todays’s thinking about open source, internet art, biohacking, robotics and fablabs.

Counterculture and arts establishment

The book is hard-hitting about some of the failures of the labs as a flashpoint between the 60’s ‘counterculture’ and the art scene of the time. While as Andrew Wilson points out in the introduction, the Arts Labs were ‘part of a counterculture that led to an ethos of immediacy of decision-making and an urgency of action.’ – the chaotic policies of the charismatic and often impetuous American Drury Lane Arts Lab founder Jim Haynes, who also founded the Traverse In Edinburgh – ‘my artistic policy was to try to never say no’ – led to its eventual closure. The second Arts Lab emerged after all the staff, including Curtis, walked out in protest at Haynes’ lack of consultation and apparent favouritism, at one point cancelling all the programmes for a takeover of the entire building by his fellow countryman and theatre director Jack Henry Moore of the ‘Human Family’. The account reminded me of reading in the ’70’s the feminist writer Jo Freeman ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness’, which underlines the power-hungry Darwinist nature of anarchy versus democracy. Theatre director Charles Marowitz in the book is particularly critical: “I would find myself squirming with contempt at what I had labelled as his ‘anything goes’ philosophy… Jim… has an almost boundless love of human beings… It is a sentiment that, being uncritical and undiscriminating, is irreconcilable with art.” Haynes’ idiosyncratic approach continues to this day, with his famous ‘Sunday Dinners’ in Paris, where anyone can turn up for dinner in his apartment (150,000 guests so far) and documented in the film ‘Meeting Jim’.

The arts establishment also got some cracks in, largely because of the drug-fuelled association with IT (International Times) and alternative psychedelic culture. This was at the same time Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Robert Fraser were very publicly arrested for drugs at Richards Redlands home. But with contributions coming in from popular culture icons like John and Yoko, who exhibited (albeit anonymously, with discarded objects on the floor) in Drury Lane, the winds of change blowing through the Arts Lab were difficult to ignore. However, as Curtis says: “I don’t think the establishment (Arts Council, BFI, art press, BBC) had any awareness of the seriousness and energy in the ‘counterculture’. The success of the Beatles and Stones, and probably of Pop Art seemed a surprise to them. They didn’t know how to respond. And as so often, the rightwing response was ‘suppress’”. The great and the good (for example Arts Council of Great Britain Chair Lord Goodman) also hummed and hawed about funding although the too-difficult-to-ignore explosion of creativity did force the Arts Council to form a ‘New Activities Committee’ in the early ’70’s, to which Curtis was invited to join.

The new London Arts Lab entered the history books as the venue for J.G. Ballard’s ‘Crashed Cars’ exhibition, with real crashed cars. How did Ballard come to get involved – the suburban culture guru with a notable dislike of the ‘alternative’? Curtis: “Ballard was a friend of Pam Zoline’s (one of the organisers in both Arts Labs and who documented a lot of the activity in writing). He admired her writing. There’s a Ballard, Steve Dwoskin (another film-maker closely associated with the Labs), Carolee Schneemann connection, so he certainly had an interest in some aspects of alternative culture.”

Subjective journeys in memory

The ‘Arts Labs’ book, as Curtis admits, is a very subjective account. What did Haynes think of the book? Curtis: “I was nervous because I wasn’t sure how he’d take my implied criticism of the financial recklessness and his absolute devotion to Jack, which scuppered Drury Lane… Anyway, he’s very frail these days but he just mailed me a one-line note from Paris saying ‘the book about the Arts Labs is superb! Great to read about our crazy days and nights in London in the 60s’.”

I have to say I also found the book fascinating, not least because I was actually there, as a teenager and aspirant arts journalist, at both of the Labs. I remember spending nights at the ‘Soft Cinema’, falling asleep during Godard films, Warhol’s ‘Chelsea Girls’ (failing to appreciate the fact that these films, sourced and programmed by Curtis, were some of the first-ever screenings in London) and seeing Tuli Kufenberg from the Fugs’ ‘Fuck-Nam’ after a day street-selling, as I did, International Times. I was also part of the founding of a ‘satellite’ Arts Lab in Southampton, part of a national explosion of over 150 Arts Labs in the UK, most famously including David Bowie’s Beckenham Arts Lab, and Alan Moore (The Watchmen) at Northampton Arts Lab.

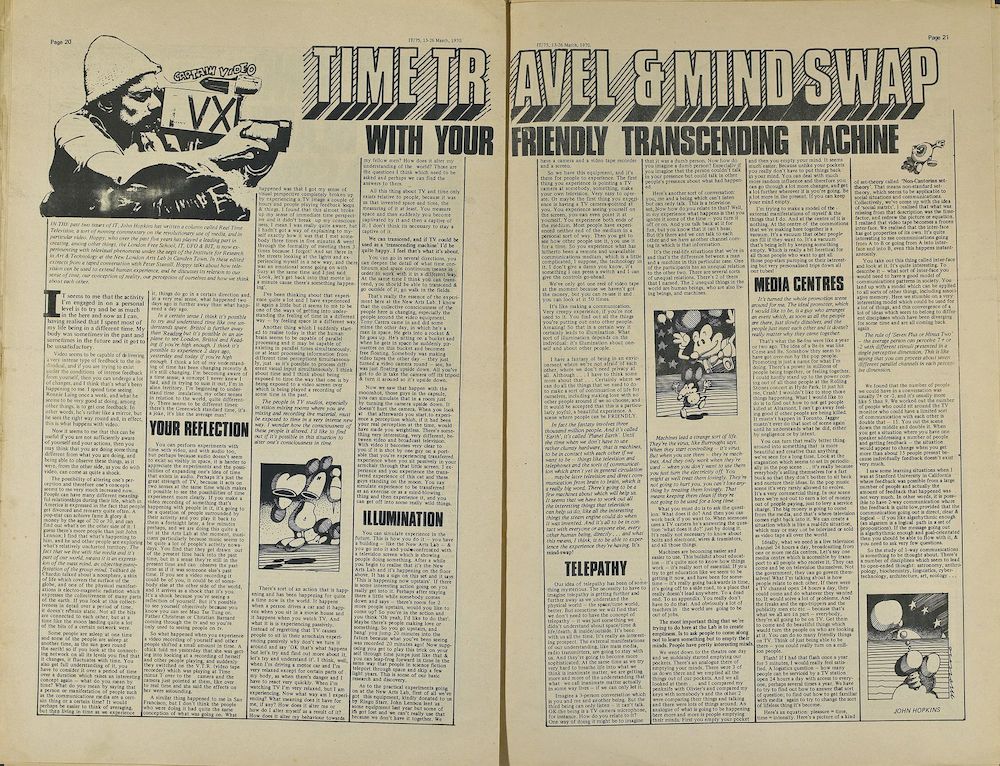

More importantly, I was, as an early media-art aficionado (I had already visited Cybernetic Serendipity’ as a school student and had painstakingly read McLuhan’s ‘Understanding Media’ which popularised the term ‘the medium is the message’), able to learn to use half -inch video at the New London Arts Lab using the early Sony portapaks and edit reel-to-reel with stopwatch and chalk with the great pioneer John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins (I had met him, videoing entirely naked except for a portapak on his back, at the Isle of Wight Festival in the summer of 1968). He described early video in an article in IT as “Time travelling and Mindswap with your friendly transcending machine”. Hoppy also introduced me to early slow-scan video, which I have described elsewhere in an essay called ‘Subversive Transmissions’, as a “way of transmitting a video signal down a phone line, bouncing off a disused satellite, or simply throwing it out into the short-wave ether. In fact radio hams have been doing this for years, as John Hopkins discovered when he tuned his robot transceiver (the basic device for decoding slow-scan signals) to those frequencies. On his collection of slow scan tapes is included a striking but naive decoded image of someone’s cat, sent out from eastern Europe (during the Communist era) along with friendly greetings scrawled out in various languages. To watch it feels rather like being the recipient of a first message from an alien planet… the intense personal reaction to the opening of a new form of communication which can become an art form in itself.” Being at the Arts Labs as a young person formed my thinking for the rest of my life.

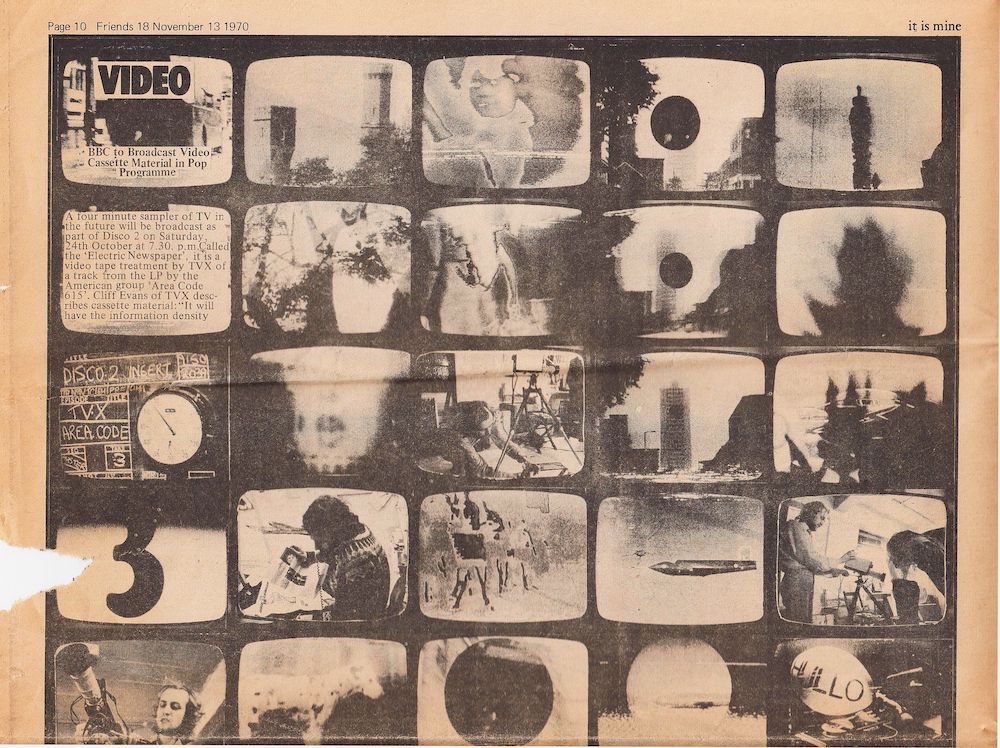

I was also, unusually, watching actual television one night back in the suburbs during the Lab era when Hoppy, Jerry Rubin and the Yippees invaded the high-ratings Frost programme live, wielding Sony portapaks, on commercial television. Hoppy speaks of this famous intervention in the book: “The hijacking of the Frost programme by media guerrillas is the direct result of young people being denied access to television.” Again, directly anticipating the open source movement, he quotes a TV director: “Television is dynamite… and we’re leaving it around for any idiot with a match.” Hoppy: ‘We are neither fools not fanatics nor idiots… next time we will be able to plug our own programme into the transmitter.” The BBC took up his challenge and commissioned a 4 minute slot called ‘The Electronic Newspaper’. I was lucky enough to meet Hoppy again shortly before his death in 2015. A true pioneer of our age.

The art programme, programmed by Biddy Peppin, was also prescient in that many later major figures in the British and international visual art scene in the 70’s, 80’s and beyond were given a first outing at the Arts Labs, such as Carolee Schneemann, Ian Breakwell, Valie Export, John Latham, Takis, Peter Weibel, Jeff Nuttall, David Medalla, Graham Stevens, The Exploding Galaxy, Ken Turner, Mark Boyle, Mike Figgis, Carla Liss and Kurt Kren. Performance art was also starting to be represented at the new London Arts Lab in a participatory performance work ‘Dark Touch’ by Anna Lockwood and Harvey Matusow, inspired, the book suggests, by Dianne Lifton’s ‘Touch Experiment’. The press release was stamped ‘Nude critics only’. It sums up the era.

‘London’s Arts Labs and the 60’s Avant-Garde’ by David Curtis, John Libbey Publishing, October 2020.