Mélodie Mousset: Projecting the body into virtual reality

Published 3 October 2020 by Ewen Chardronnet

For Ars Electronica 2020, the French artist Mélodie Mousset was both on site in Linz and presenting her work during the “Silicon Valley Garden” panel of the virtual festival. We met her between Linz and Zurich, where she currently lives, to talk about her journey from contemporary art to virtual reality.

As Chris Kraus, the authoress of I Love Dick, wrote: “Mousset’s associative process is so rich. She fully believes in her own imagination and in the logical or alogical digressions that shape an inner life.” Perhaps it was this shaping force that led Mousset to study art in Rennes, France, followed by Lausanne (ECAL), London (RCA), and Los Angeles (CalArts). She even traveled in cargo all the way to Mexico, carrying her own organs reproduced in wax, in order to place them in a symbolic cave, as if reassembling the pieces of herself at the end of a pre-Colombian quest. In 2018 and 2019, Mousset’s virtual reality work HanaHana was awarded and exhibited around the world.

Makery: How did your personal journey evolve toward Virtual Reality?

Mélodie Mousset: I’m a visual artist. I did a bit of everything: sculpture, performance, photo, video. My work is always related to the body and the expansion of the body, the possibility of inhabiting different bodies, or transforming oneself through artistic practice. In this sense, each one of my artworks is an interpretation of one stage of this transformation.

I stumbled into VR as I was trying to “remove” my organs from my body. I contacted hospitals to do MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and make replicas of my organs, in order to take them out of my body, have them outside myself. I wanted to reconstruct myself with my own hands. It was a metaphor for biological determinism through a surrealist narrative, a journey to Mexico where I would meet shamans, bring them elements of my body, and engage them in a magic ritual…

When I met the MRI researchers, my research topic was: How can MRI images influence the proper neuronal connections of patients simply by visualizing them in real-time? I tried to get them interested in my magical organs project, but they didn’t take it seriously at all. Then one day I walked in when they were setting up a Cognitive Behavior Laboratory, in VR. In 2013. I had my reproduced organs on my USB stick. I asked if I could inject my organs into their system.

The virtual environment was a CAVE [Cave Automatic Virtual Environment, projected on four walls, floor and ceiling]. This was before my Oculus. So my first VR experience was totally introspective, I visited my uterus, my lungs, etc. It was totally wild. I started working with this hospital engineer. Then the Oculus DK2 was released. So I wanted to import what I had done in the CAVE into the glasses. That’s what led to my first VR application, artwork. Afterwards I made HanaHana.

“HanaHana: Full Bloom” (2018) – VR excerpt:

Makery: What is HanaHana?

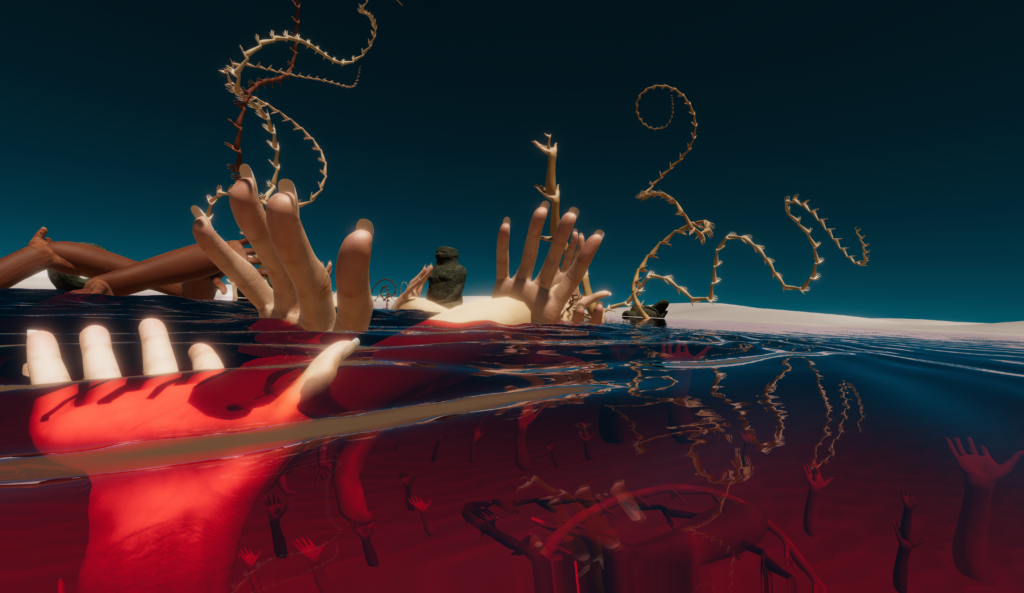

Mélodie Mousset: HanaHana is a sandbox, an open world, a kind of surrealist, psychogeographical desert. The sand is like a skin, in the center of which is a big lake decorated with five monumental anthropomorphic sculptures. Each one of these forms is a phase of my disfigurement: from a scan of me sitting in the lotus position to my transformation into Torus—I call it Lotorus—a topological form with one hole, passing through a canal in my body that follows a toroidal field [somewhat aligned with the chakras].

The building block of HanaHana is not a cube like in Minecraft, but women’s hands. In this world, users can grow hands and chains of hands of all sizes and colors. As the piece is exhibited, like a three-dimensional cadavre exquis, they create a sort of improbable forest. It’s a contemporary mythical world, in the Anthropocene age: colonizing the human hand in a CGI world without any other form of life. As a player, you don’t really have a body, a shape, skin, you are a kind of creative vital energy.

I took the experience up a notch by adding a multiplayer option to live the adventure together, to explore and communicate, but through expressiveness and emotions, rather than words. This way, the piece gradually drifted toward music, procedurally generated sounds. When the hands are facing each other, they produce an electric arc between the palms, which makes sound. Players can “take” the arcs, share them. When you move them it produces a sort of theremin—that you can play online with people all over the world.

“HanaHana (2018) – Connection Plasma”:

How long did it take to develop HanaHana?

Mélodie Mousset: I worked almost four years on this project. It was a real journey into this world of technology that I knew nothing about. I learned about VR production and computing in general, while making tons of mistakes, of course. Developing stuff organically and with no plan, as I was used to doing before in other art forms such as sculpture or performance, is the worst thing in computer programming, when the architecture of the code is not designed to evolve later.

Then I had to find developers who understood what I wanted to express artistically. It didn’t happen overnight, but I finally found great people to form a small team of warriors. These days, we’re still working together remotely. Not one of us lives in the same country, and it works really well. Our pace is pretty freestyle, but sometimes we also crunch… even though we’re not making AAA games.

Makery: The piece was pretty successful?

Mélodie Mousset: HanaHana has been shown in more than 70 exhibitions and festivals since 2017. I’ve been unintentionally projected into the worlds of video games, technology, industry. For example, I was selected to present HanaHana at Gamescom in 2017 and 2018, with the Swiss delegation. The first year, I even made The Guardian’s shortlist of the nine most “weird, wonderful and odd” games of the year—which made me laugh, because I had never created HanaHana as a video game… But I adored the community, the others developers, who gave me feedback, helpful advice. It was a completely different approach from exhibiting in museums.

Since then, I’ve received many awards, in various festivals, and millions of hands have been made by users from Siberia to Rio de Janeiro, to Shanghai, to Pougne-Hérisson. Actually I made the beginner’s mistake of exhibiting the work before it was finished, instead of premiering it at a festival, as is customary these days. But this makes it an iterative work, and it’s very possible that I’ll return to it. Since Covid, and the closure of LBE [Location-based entertainment] and museums, I’m thinking of releasing it on Steam… in multiplayer mode, that could be very, very funny.

#Gamescom2018 Come to see @HanaHanaVR and create your own artistic experience in VR ! Amazing and very different from a video game ! Hall 4.1 Swiss pavilion C10-D19 @gamescom pic.twitter.com/EtPvaCpLMn

— Mélodie Mousset (@HanaHanaVR) August 21, 2018

Makery: How did you finally come to develop a VR tool for making music?

Mélodie Mousset: I was presenting HanaHana at Nordic Game 2018, a festival for independent video games held in Malmö, Sweden. At the opening party, there was a concert by the rock group Die A Little, and one of the guys on stage was playing this crazy instrument in virtual reality. I thought that was so cool. I met Edo [Eduardo Fouilloux], who created the instrument. At the time, the VR application was still in beta and called MuX. It was a sort of steampunk lab where you could connect modules, make patches, synthesizers, basically make music in a world somewhere between Alice in Wonderland, Max/MSP and Rick & Morty. We hit it off right away, our work overlapped, we had the same sandbox approach, surrealist, both artistic and super ambitious technically. We stayed close, giving each other support, because the world of VR can be pretty tough. Funding is hard to come by, teams of developers and engineers are expensive, etc.

What is MuX? (teaser), 2017:

In 2019, I was invited to direct a dance performance in HanaHana for the opening of the VRArles festival. Technically, it involved a lot: three dancers in multiplayer mode wearing VR backpacks, who had to dance, produce a film and music in real-time. I asked Edo if he wanted to collaborate, and everything just clicked—especially with Victor Beaupuy, our technical artist, and Christian Heinrichs, founder of Enzien Audio, who is a genius of procedural sound based in Malta and who has been working with me for two years already.

We started creating “Jellyfish”, a system for visualizing voices, where everything is connected: visuals, sound, motion (the jellyfish moves and comes to life through the user’s voice). It’s a hypnotic communication with a being that is an externalization of yourself. The prototype was presented at Laval Virtual this year, and we hope to premiere it at Sundance New Frontier. It was after this experience that we decided to join together to found the studio PatchXR. We revisited MuX with the idea of pushing the C++ engine the furthest possible toward a tool for creating musical instruments in VR [VRMI, Virtual Reality Music Instrument].

“Jellyfish Always Cared”, Eduardo Fouilloux, Mélodie Mousset (gameplay recording):

‘HanaHana’ is exhibited at Helmhaus in Zurich through November 15, 2020.

Vote at Prix Opline.