ArtLabo Retreat: Living symbiotically on the French Island of Batz

Published 22 September 2020 by Roland Fischer

From August 16 to 24, Makery held its first “ArtLabo Retreat” on the Island of Batz in France. The event was an encounter with the ArtLabo network, part of the Feral Labs network series launched in 2019. Roland Fischer from Symbiont.Space in Basel writes about his experience.

The periphery is the new center. And vice versa. Paris was almost empty in mid-August, but I was just passing through. Three hours west of the capital, the train was was practically full. Rain welcomed me in Morlaix, and another half-hour later I was sitting on a cafe terrace in Roscoff, on the northern coast of Brittany. The air was salty, the rain had stopped; the weather is fickle here. Final destination: Batz Island. Tidal range: maximal. Temperature range: minimal.

This geographical exception would be the perfect location for a week of exchanging with folks from all around Europe working on art-science projects—at least that was the plan before the Coronavirus struck us with its particular understanding of symbiosis. It turned out that Brittany was somewhat of a safe haven, as its number of Covid cases was among the lowest in Europe. Many people who had intended to come from abroad decided to stay at home nonetheless, given all the travel restrictions. The French, however, flocked to the island—Brittany’s remote coastline had never seen such a busy holiday season.

Distinguishing themselves from the flurry of tourists who were more interested in hiking and sunbathing, some 20-30 individuals gathered on Batz Island for a weeklong communion of experiments and discussions. As part of its activities within the European Feral Labs Network, Makery organized its first summer camp there: ArtLabo Retreat. Conceived as a meeting between the European Feral Labs network and the French ArtLabo network, the retreat provided an opportunity to share research and creative practices in Art/Society/Technologies.

In search of symbiosis

The theme of the retreat was “symbiosis”, in very broad terms: long-term partnerships between organisms, merging different skills or abilities in order to “upgrade” the system as a whole. Of course, this relationship holds true for many art projects as well, especially at the intersection of art, technology and science.

So it was quite fitting to kick off the event with a screening of the documentary film Symbiotic Earth about the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis. An eminent figure of modern biology, Margulis was often ridiculed at the beginning of her career. Her audacious idea was that evolution is not a continuous process, sometimes it happens in leaps and bounds. Abilities evolve within independent lifeforms, and something totally new and much more interesting emerges when two of these “prototypes” merge. She called it “symbiogenesis”. Instead of the mechanistic view that life evolved through random genetic mutations and competition, Margulis presented a symbiotic narrative in which bacteria joined together to create the complex cells that formed animals, plants and all other organisms—which together form a multi-dimensional living entity that covers the Earth. This also implies that humans are hardly the pinnacle of life itself, with the right to exploit nature, but simply one part of this complex cognitive system. As Margulis says in the film: “Bacteria have been here for billions of years, long before we arrived. They rule the world.” We could add, with the current headlines in mind, that viruses are certainly part of that old empire too. They might even be the discrete kings of symbiosis, but that’s a different story.

Trailer for “Symbiotic Earth”, documentary by John Feldman:

The screening was followed by a discussion led by Xavier Bailly, researcher of the Multicellular Marine Models laboratory of the Roscoff Biological Station and an expert on the local symbiotic hero: Symsagittifera roscoffensis, a marine worm that ingests algae to use them as energy supply—a truly exceptional “animal-plant” of the Brittany coastline. His presentation sparked a debate about symbiosis vs. parasitism. Who is exploiting whom in this merger of animal and algae? Is symbiosis always beneficial for both partners? And surprise—according to Wikipedia, we’ve been wrong about symbiosis all along: Symbiosis (from Greek συμβίωσις, sumbíōsis, “living together”, from σύν, sún, “together”, and βίωσις, bíōsis, “living”) is any type of close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic.

So, even parasites can be symbionts? Nature doesn’t seem to insist on consensual relationships. Xavier Bailly showed recent close-ups from his lab exposing the algae in very “unnatural” forms. It looks almost as if they were constantly trying to flee their new habitat inside the worm’s body. So what about the arts? What are the power structures when it comes to art and science collaborations? Who is embracing whom here? Still much too often, these kinds of projects are shaped by hidden hierarchies—just follow the money. Scientists tend to exploit the arts according to their needs: popularization, illustration, creativity (a.k.a “thinking outside of the box”). In these contexts, the metaphors of mutual vs. parasitic can be used to reflect on structural and political framings of artistic collaborations, whereas Margulis herself warned about the dangers of using anthropomorphic concepts when describing or analyzing biological phenomena.

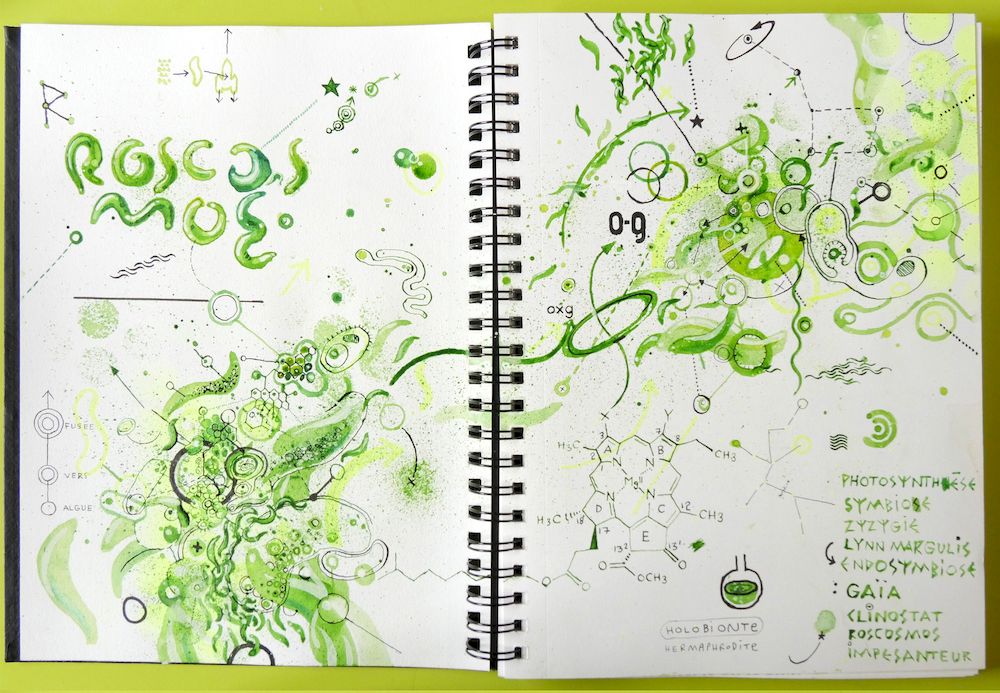

The Roscosmoe project, hosted by Ewen Chardronnet, takes the Symsagittifera roscoffensis story one small step (or one giant leap?) further, into space. The project narrates the journey of S. roscoffensis through the stages of its selection as a “cosmonaut candidate” in view of its possible departure for extraterrestrial space. Should we see the “animal-plant” as the perfect space explorer, living solely on the energy of the sun?

Feral energies

Speaking of solar energy, the Energylab, hosted by Cédric Carles and Loïc Rogard from Atelier21, presented fantastic innovations from the history of energy: pioneering devices that were not considered relevant or reliable in their time, did not find interested users or lacked a technical brick to make the system efficient. As they say: “Inhale the past, Exhale the future, Fly with the sun”. A recent descendant of the solar flight pioneers was present on the island as well. Weather permitting, sometime over the course of the week they had planned to fly the solar balloon Aerocene Backpack from Aerocene Community France, hoping to send a GoPro camera high up in the air. But as mentioned previously, the weather is fickle: after a moment of sun there were too many clouds, so instead of a research device, the balloon ended up being a huge and surreal black toy for the children on the beach. But that worked just as beautifully.

Meanwhile, Joachim Montessuis invited everyone into a think-tank, an ephemeral discussion-debate group about art and consciousness, based on his course on sound and spirituality at Ecole Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Strasbourg. Is the artist’s subjective ego (or even collective ego) still a sufficient notion nowadays? Can we go beyond the existentialist binarity of the ego of the artist who is master of his reality and his destiny, in order to gain a deeper experience? Who creates, for whom, and for what benefit? Back to the debate around symbiosis and parasitism.

Channeling a more substantial kind of spirit, I decided to expand my experiments in sonic maturing to local applejack liquors, injecting them with high doses of ultrasonic energy. Is this physical chemistry or succussion quackery, as practiced by homeopaths? What happens to strong alcohols when they are stimulated with ultrasonic waves? When they are basically shaken very hard, from the inside out? There is a tradition: “The color and flavor of Kentucky bourbon came from the rocking on the water. Bourbon was loaded on to ships in Kentucky, and by the time it traveled to the people buying it, the flavor improved.”

The Margulis documentary found a surprising echo two days later in Spaceship Earth, a film about the most unlikely partnership of late capitalism: Biosphere 2 and Steve Bannon. Pity both films were terribly conventional, artistically speaking: first-person narrations, talking heads. In contrast, some of the presented projects offered somewhat different and more rhizomic experiments in cultural-technological practices.

Trailer for “Spaceship Earth”, documentary by Matt Wolf:

Radio-Batz

A few members of MyOwnDocumenta (Corisande Bonnin, Charlotte Imbault, Dominique Petitgand) also joined the retreat. MyOwnDocumenta (artists publishing works-in-progress and diaries hosted by David Guez) is a group that believes that the process is probably more important than the final result, which was certainly the case in discussions of the ArtLabo network led by Julien Bellanger and Catherine Lenoble. Their workshop was held all week long in the studio of the colony, a beautifully strange space full of toys, painting accessories, holiday leftovers. There the hosts invited all participants to discuss and test tools and practices related to documenting and sharing our experiences towards more digital autonomy. Along the way, the colony became an ephemeral radio station, broadcasting on Pi-node. It sent out signals in the dark, just like the lighthouse on the hill above the colony, as its beam continued to rotate, blinking out its message to the black seas. But wait, is there a signal even when there is no one to see it?

More on ArtLabo Retreat.

ArtLabo Retreat is part of the Feral Labs Network, co-funded by the Creative Europe programme of the European Union.