Covid-19: Italian makers take action

Published 22 June 2020 by Enrico Bassi

In Europe, Italy was the first country to be an epicenter of the novel coronavirus. As a result, mobilized Italian makers showed the way for makers around the world. Enrico Bassi of Opendot fablab in Milan, specialized in open healthcare, tells the story.

Italy was one of the nations hardest hit by the Covid-19 epidemic. For weeks on end, the number of deaths and cases continued to increase, especially in the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto. Their respective health systems, considered to be the most efficient on the Peninsula, were brought to their knees. As hospital supplies ran out, personal protective equipment (PPE) became a rare find, as were essential parts for ventilators, CPAP machines, etc.

At Chiari hospital, the situation was dire: all the Venturi valves required for mixing oxygen and air were currently in use, and the company that produced them could not supply new ones fast enough. So Cristian Fracassi and his team from the company Isinnova brought a small 3D printer to the hospital, redefined the shape of the piece, printed and tested it in record time. But these fused filament fabrication (FFF) printers could not reliably produce precise or sterilized pieces, so after a few tests, hospital staff decided to use pieces produced by sintering.

This first mobilization unified the heart’s generosity, the brain’s tech-savvy and a good dose of courage—this kind of experiment had never before been tested in such conditions. News spread around the world!

Complimenti a Cristian Fracassi, @temporelli73 e tutte le persone che lo hanno aiutato nella impresa di stampare in 3d le valvole mancanti per i respiratori dell'Ospedale di Chiari a Brescia.

(qui l'articolo completo https://t.co/QYZu6x9X1T) #SolidarietaDigitale #iorestoacasa pic.twitter.com/dF3G2RJY8S— Paola Pisano (@PaolaPisano_Min) March 15, 2020

However, considering the delicate nature of the project, the files were never made public, and Fracassi himself advised against producing similar solutions with non-professional technologies. He emphasized that this experiment could only be done as a last resort in an emergency situation and that industrial products should always be the preferred solution… when available.

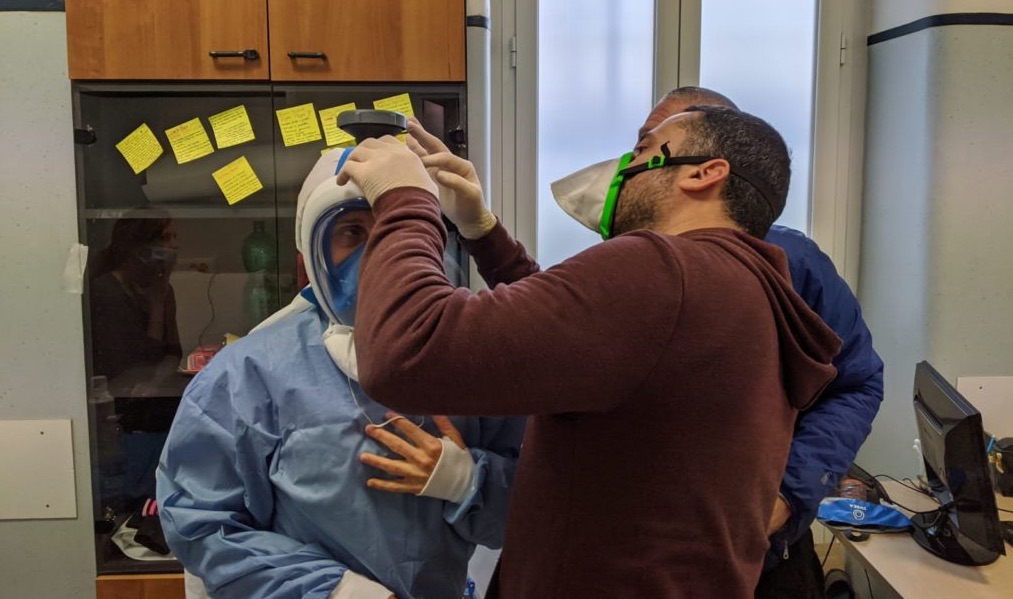

Nonetheless, it wasn’t long before Fracassi’s team was contacted by Renato Favero, a doctor and former director of Gardone Valtrompia hospital. He wanted to share an idea that could potentially help overcome the temporary shortage of CPAP masks for non-invasive ventilation. Could they modify scuba-diving masks using 3D-printed valve adapters, based on the open source models published on Isinnova’s website?

Charlotte valve demonstration video uploaded on March 22 by Cristian Fracassi:

Given the simplicity and efficiency of this new project, the idea caught on fast. Some makers began contacting nearby hospitals, where they already knew a staff member, to offer their services. In other cases, it was the hospitals that asked for help. As these requests grew in scale, people began to coordinate a timely response to the crisis.

The first order came from Brescia: 500 adapters. Isinnova, associated with a fablab in Brescia, posted a call for contributors on Facebook on March 22, which received hundreds of comments and was shared thousands of times. Within 24 hours, the distributed maker community had produced and even surpassed the required number of adapters!

But there were still some problems: how could they verify the quality of the pieces, avoid overproduction and manage delivery while under lockdown?

Despite a few difficulties, this first experience in distributed production exceeded expectations. International projects aiming to find similar solutions to improve the supply of PPE for healthcare staff and other essential workers also began to emerge.

Coordinated actions

Local coordination groups formed or mobilized to produce and distribute parts for such projects. These groups were almost all volunteer-based, almost always within existing communities of people or fablab networks who were already used to working together. The first Covid-19 maker networks in Italy were regional, and they succeeded in responding to local needs as they evolved.

Makers Sicilia united Sicilian makers, fablabs, innovation startups and incubators to respond to the crisis in Sicily. Since it was founded in late March 2020, the group regularly meets online to share updates on local projects, examine ongoing experiments in local hospitals, exchange information on certifications and necessary legal procedures. Members have also contributed to purchasing materials.

Makers Sicilia live call on May 10, 2020 (in Italian):

Officine Mediterranee is another network that is active in the south of Italy. It unites makers, fablabs, associations and small businesses involved in digital production across the regions of Basilicata, Puglia and Campania.

According to Alessandro Bolettieri of Officine Mediterranee, “The group formed in response to a request for 500 face shields from Basilicata’s emergency coordination number (118). In about 40 days, we managed to produce and distribute more than 2000 face shields, as well as over 50 Charlotte valves, mask ear-savers and 20 intubation boxes, in collaboration with Open Design School in Matera.

Officine Mediterranee has around 50 members: makers and other professionals assisting with coordination and communication. Their group work is recounted by its members through a series of “Daily Diaries” shared online.

Makers at school

In retrospect, the projects led by Indire (National Institute for Documentation, Innovation and Research in Education) are particularly interesting. This historical institute has been active in the education sector for more than 90 years. A few years ago, it began exploring the relationship between schools and making through the Maker@Scuola project.

After co-developing with doctors a face shield model that was adapted to their needs, the project branched off in two non-emergency directions: on one side, Indire collaborated with a big company to produce the shields on an industrial scale; on the other side, the face shield production model was integrated into company simulation training for students in technology and technical high schools.

Progetto di ricerca Indire ?????@?????? ??? ?’??????: da oggi il protipo di stampa 3D e le istruzioni per assemblare visiere protettive per medici e infermieri sono disponibili online per tutti! https://t.co/wUz0cwuzsd #Indire3DPrintSquad #COVID19 pic.twitter.com/CqXD6FldZH

— INDIRE (@IndireSocial) April 8, 2020

In Veneto, following a regional competition in 2015, funding was provided to 18 fablabs to seed a Venetian network. FIve years later, some labs have closed, while others have joined the network. The region of Veneto posted on the Innovation Lab website the main activities and potential contributions of these fablabs, in addition to the contributions of makers, volunteers and businesses eager to help.

Nationwide coordination

This teamwork at local and regional levels paved the way for nationwide coordination across Italy. In the period of just a few days, three different initiatives emerged with similar and complementary objectives.

Tech For Care is the result of a collaboration between Maker Faire Rome – The European Edition and I-RIM (Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines). This platform is not only a place to share projects, it also lists needs from frontline workers and proposed solutions from the maker community, startups and research institutes linked to the two project founders.

Opendot, the fablab that I coordinate, operates in the healthcare sector. For this reason, we were involved in implementing the project from the beginning. Tech for Care was also presented during Virtually Maker Faire on May 23, 2020.

Watch the entire presentation:

Some of the published projects come directly from the partners. For example, I-RIM developed a telepresence robot that can be easily assembled from pieces bought online or 3D printed. The project is entirely open source and published online.

Another nationwide coordination project, Air Factories is a distributed factory for manufacturing components and prototypes to fight Covid-19. The project was started in Messina, Sicily, by engineers at Innesta, SmartME.io and Neural, but it welcomes requests for solutions and volunteers from anywhere in Sicily.

An additional response “from the base” came from Make in Italy, an association founded in 2014 to promote research and coordination initiatives around digital fabrication and maker culture. After a few years of low activity, the group mobilized to coordinate supply and demand. Within a few days, they collected 500 contacts from makers, small laboratories, startups and fablabs. Their website currently lists over 25,000 items produced and donated.

Tech For Care and Make in Italy have pooled together a selection of open source projects published on Careables.org, a platform developed within the European H2020 “Made 4 You” project, with which our Opendot fablab is also associated. The goal is to find, collect and share open source solutions that are easily reproducible in the healthcare sector. Sharing projects on a common database makes it easier to collaborate between the two platforms.

Corporate makers

Italy’s response to the health crisis wasn’t limited to the grassroots maker movement of hundreds of volunteers and fablabs. Many Italian companies worked closely with active makers, and in some cases, even helped the movement to take off.

The most obvious example of that is Arduino. Not only were they behind Italy’s first fablab (I started out in 2011 as coordinator of this lab in Turin), but ever since then, they have clearly been at the technological core of innumerable DIY projects. This was further demonstrated in many solutions that emerged during the pandemic. Alessandro Ranellucci (Head of Open Source & Community) and David Cuartielles (Arduino co-founder) organized an online conference for presenting and debating projects to fight the pandemic.

Filoalfa, one of the main producers of 3D printer filament in Italy, launched the “Suspended spool” initiative to collect and donate spools of filament to support the three nationwide projects mentioned earlier.

WASP, one of Italy’s biggest manufacturers of 3D printers using filament, teamed up with Alessandro Zomparelli, renowned expert in parametric modeling, to develop an add-on for Blender allowing users to model and print a customized mask with interchangeable filters.

What are the takeaways?

These past months have been filled with excitement and fear, willingness to contribute and frustration by the limits of what was possible, enthusiasm for the generous response from so many, and sadness for the ongoing situation.

We talked about makers as Plan C, a temporary solution until the industry got organized, and it seems that a good portion of European funding for research is going to support the industrial sector. But I would still like to think that what happened during the past months was a keystone, a beta-test of what could be the role of innovative communities equipped with technology.

Many people say that this crisis has accelerated our digital transformation much more than all the policies implemented in the past years. I believe that it also demonstrated the value of those who create and practice innovation for those who need it. Five years ago, when we were talking about how digital fabrication could serve healthcare, it seemed to be a marginal preoccupation. Three years ago, when we started working with doctors and hospitals, it seemed infeasible.

These last examples are the ones that could continue once—hopefully soon—this surreal situation that we are in is behind us. Because of the emergency, various hospitals contacted specialized studios, fablabs, small businesses and startups in order to develop new solutions together.

Fablab Napoli started collaborating with Buon Consiglio Fatebenefratelli hospital to produce clear boxes to protect doctors during intubation. As is often the case, available models didn’t quite meet the needs of the hospital, so some doctors, including the department director of Fontanella General Medicine, began to design necessary variations. In light of the potential, the project was scaled up to involve other entities, including ENEA Research Center in Portici. Interestingly, the hospitals that adopted it continue to use it today as a common accessory for use during intubation procedures.

In Rome, Studio 5T had started working with hospitals early on in the crisis, especially Spallanzani hospital, Pertini hospital and Policlinico Umberto I. After an initial meeting, the studio offered to produce face shields, but the existing model didn’t meet the doctors’ needs. However, as in Naples, the doctors understood the potential of digital fabrication’s speed and flexible process. Through this collaboration, their role evolved from users to designers of solutions. Months of collaborating led to other projects, including some that are still in development.

Here in Milan, we continue to collaborate with local hospitals (4 so far) and with the doctors and therapists who work there. We have started projects together, with visible results—once people understand the potential, they become more proactive, constructive and independent.

One of these doctor-inventors, who works in intensive care, printed more than 200 ear-savers for his colleagues, safety tested Venturi valves, and printed various mask models in order to evalute their efficiency and comfort. He started a few years ago, followed basic training, and we successfully developed a model together.

We would like this type of cooperation to be the rule rather than the exception, that hospitals understand and remember the potential they saw during this period. Then perhaps we will be more capable of reacting, more quickly and more efficiently, during the next crisis.

More information on Opendot in Milan

This series of reports is supported by Daniel and Nina Carasso Foundation’s emergency fund for Covid-19.