Slower travel: new post-viral geographies in Europe

Published 8 May 2020 by Rob La Frenais

Started in 2015 as a research project in art and design with the Srishti Institute of Bangalore in India, the independent curator and critic Rob La Frenais today runs the “Future of Transportation” group on Facebook. New chronicle about mobility after the lockdown.

Recently I was asked by a Finnish foundation to write an article aiming to explain to artists what it would mean not to fly to their residencies, called Slow Travel – A Privilege Not A Sacrifice, describing a 3-day journey from rural France to the Saari Residence in Finland, using trains, electric scooters and ships. Within weeks of it being published, artists were either unable to travel to residencies or were stuck in the ones that they were in, because of the restrictions of movement caused by COVID 19. It seems ironic in hindsight that one of the conclusions I drew was “that having travelled by rail and ship many times in one year, I’m also beginning to question the need to travel at all. Slow travel doesn’t mean just substituting a train for a plane, it means changing an entire mindset.” I go on to ask the question “why travel at all?”. Little did I know. Now we have ‘home artists residencies’ and are bewildered by an online melée of endless virtual meetings, remote cocktail parties and non-stop media consumption, what will happen in Europe when we finally get let out?

Red and green zones

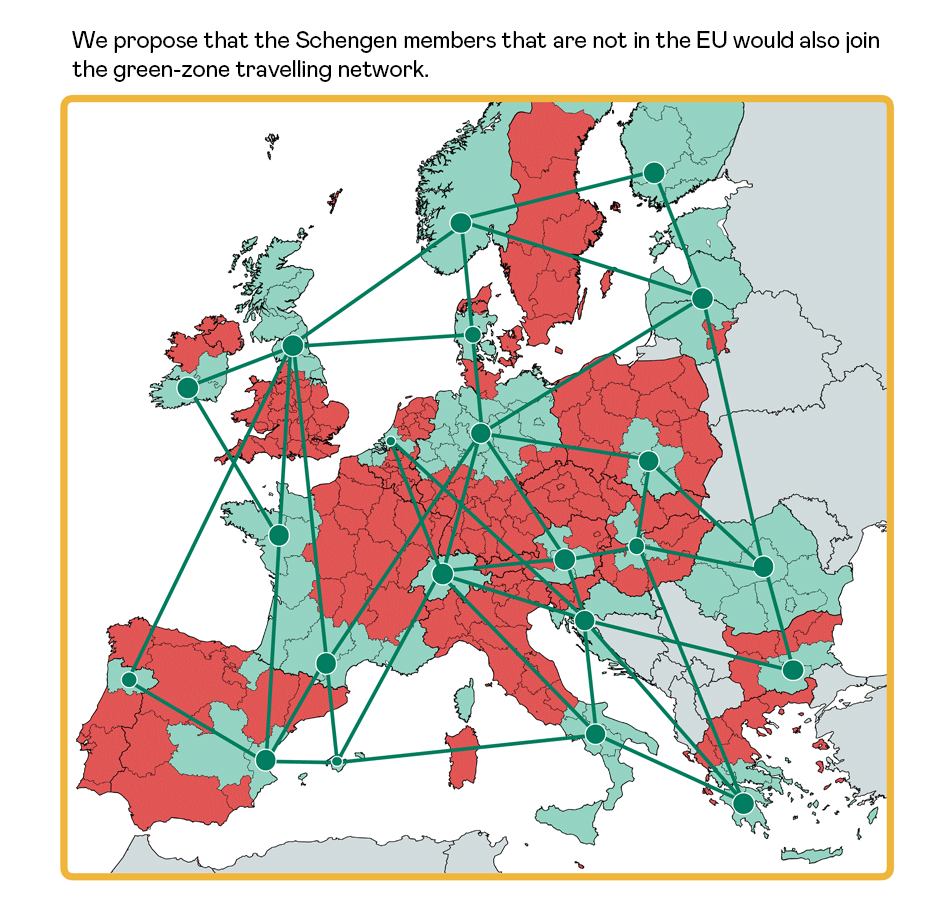

I wrote in my last article here suggesting we should rethink and retool the aviation industry post-crisis; now I ask whether the new post-viral mobilities will be determined by where we can and can’t travel, with ‘red’ and ‘green’ zones opening and closing and the fast crossing of Europe’s borders, within Schengen at least, no longer guaranteed, with unpredictable second-wave health crises arriving to restrict our movement again. Perhaps in our future travel plans we should avoid the fastest routes from A to B and instead flow the example of Charles Baudelaire when he adopted the notion of the flaneur, or aimless stroller, in our approach to getting somewhere. With very few Eurostar trains running, it may be that we go back to the old routes, getting to the mainland from the UK by ferry boat, then using local trains and buses or even using ships to get between European destinations. There is already a movement for ‘scenic trains’ where the journey is more important than the destination, as shown by the UK-based Community Rail Network.

It’s been made quite difficult to avoid the set routes long before the crisis. Travelling by local train to the coast from London to France, as I did recently, transferring as a ‘foot passenger’ by ferry, one is made to feel like a pariah compared to those using cars or the tunnel and one feels closer to the mechanisms in place for discouraging undocumented migrants. In France whole swathes of the rail network are dedicated only to the TGV. It is virtually impossible, for example, by using TER trains and changing, to get from Paris to Bordeaux. The whole approach to train travel is geared to speed and competing with the airlines. I’d like to think that a post-crisis scenario might be to avoid these routes (safer as well in terms of not being exposed to the virus) and travel by electric bike or scooter or even a horse and cart. In 2013 a retired couple, Michael and Jacqui Burden made the headlines in the UK by using their Freedom pass (free bus pass for pensioners) by travelling over 500 miles hopping on and off 24 buses between Devon and Cumbria, only to stop at the Scottish border as the pass was not valid for Scotland. Maybe this is a premonitory view of what is to come as people re-negotiate how to get out of the lockdown.

47 days at sea

Several groups of people, or crews, have been completely isolated on the high seas during the outbreak of the virus. These include two fair-trade ships featured in previous articles, the Tres Hombres and the Gallant. I asked Alexandra Geldenhuys of New Dawn Traders, who was waiting for the Gallant to arrive in Falmouth as I wrote, how the crew felt about arriving to an empty port in a locked-down country after sailing from the Caribbean. “Captain Jeff said it was strange to sail into the harbour without the usual ship traffic. It was such a pleasure to see the crew again after so long. They spent a total of 50 days at sea crossing the Atlantic, leaving Mexico before the global CoronaVirus lockdown. They received some news about it whilst at sea but couldn’t easily find out information about the safety of their friends and family. When passing the Azores the crew were able to send and receive a few messages to put their minds at rest for the remainder of the voyage. Luckily all are well, healthy and happy and have otherwise had a splendid time together.” Normally the arrival of the Gallant is a cause for celebration, with music and dancing as the goods are unloaded and sold straight away to the waiting suppliers and customers but this time they are having to rely on mail order. At least the Gallant can still operate. “As a registered cargo vessel, it can still operate to deliver goods whilst similar looking vessels, that would normally do passenger charters are in lockdown. This means that we can continue with our work building ethical supply chains. We bring together a network of family farms, sailors, makers and port allies, who together supply our customers with almost zero emission transported goods that cannot easily be grown locally – like olive oil, almonds, coffee, chocolate, wine etc”

The Tres Hombres also arrived in France after a similar voyage carrying fair-trade goods under sail. Captain Weibe Radstake wrote in her blog mid-April about the uncertainties of return ” ‘You’re not the only one with mixed emotions, you’re not the only ship adrift in the ocean’. I remember this was the Rolling Stones song we listened to on the first crossing I did with Tres Hombres seven years ago. And I’m listening to it again now. Fighting our way to the Channel entrance. The last days were cold days, winds from the North East and sailing full-on by. It seems we may not be allowed to sail back home, but do we really want to sail back home? How are we gonna find Europe? Mixed Emotions.” The Tres Hombres made it into the bay of Dournanez on the 28th of April to shelter from rough seas and continued to Amsterdam followed for 5 days by a bottle-nosed dolphin. Radstake: “Now we are sailing or better surfing in the channel in the right direction. As we say in the Netherlands: Het paard ruikt de stal! (The horse smells the stable!) We are looking so much forward to see our families and friends even though we have to act differently with the 1.5 m rule.” Coming from the Dominican Republic, the crew spent a total of 47 days at sea without touching dry land, the duration of the entire crisis.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Fairtransport Shipping (@treshombres.shipping) on

Out of the present

Another crew isolated from the crisis were the occupants of the International Space Station, who arrived back in Russia on April 17th. Star City, the training centre and base for cosmonauts, has had its own mini-outbreak, so the recovery crew had to remain in quarantine for at least a month. Jessica Meir, who took part in the first all-female spacewalk (it had been delayed because NASA had not supplied enough female-sized EVA suits!) spoke to Steve Colbert’s ‘Late Show’ live from the ISS just before the return mission. “It has been very surreal because we’re up here going about our normal day. The whole issue has been pretty transparent to us because our ground teams are also affected, but it’s really a seamless transition in continuing to get our jobs done up here. We’re talking to our family and friends and we’re watching the news feed so it’s a little bit difficult for us to believe we are truly going back to a different planet. We were the only three humans not affected by this, while billions of humans were dealing with this and the three of us weren’t, so it is very strange to see all of this unfold.” Of course ISS astronauts are very used to isolation, so they have been giving advice to people locked down on Earth on how to deal with isolation. She and the crew landed safely and are still in lengthy quarantine, as the body becomes more vulnerable to viruses after a lengthy mission. She described her landing to ‘Vanity Fair’ “I was actually quite surprised by how soft of a landing it was. The strange part was, the hatch opens and there are these rescue teams there, all wearing masks—and suddenly we’re part of this brave new world of COVID-19.”

Borders and crossings

Moving back from orbital space to Europe and from hard science to science fiction, I found myself reading during the crisis Dave Hutchinson’s 2016 The Fractured Europe sequence, which like many things these days seems strangely prescient, not only of the crisis – in the books, set after a breakdown of the EU, there has been a ‘Xian Flu’ which has killed millions of Europeans, borders have closed and mini statelets have formed, including a railway line that has become a nation-state – but also Brexit in that there is also “another Europe—a sort of pocket parallel universe, sharing the geography of our Europe, accessible from here at only a few points, and entirely colonized by English people.” Accessible by various portals, including one in the shadow of Heathrow and in tunnels under the city-state of Bremen, ‘The Community’ – the name for this parallel Europe – is a strangely homogenous, nostalgic anti-technology society where everyone is white, the food is bland and terrible and people dress in drab clothes. They also have the Bomb and the atmosphere here is rather like a combination of 50’s Britain and the former Soviet Union. Rather like the foam-flecked fantasy of ideological Brexit fanatics, in fact. There also is an organisation who operates rather like people-smugglers called Les Coureurs Du Bois who specialise in getting people over borders and through the secret portals that connect the new, fractured ‘Europe’ to ‘The Community’. Maybe in our new meanderings around a fractured post-crisis Europe we need a new group of experts to help us get around.

One such expert who has been operating in this territory for a long time is the artist/activist Heath Bunting of irational.org. A tree-climbing provocateur who has been banned from the US for his ‘genetic art’, Bunting has been working on a project, BorderXing, since the ‘90s where he has been walking and documenting border crossings as they have been shifting during and since Schengen, presented recently in a collective publication called the antiAtlas of Borders and described here: “BorderXing is an online guide and database on how to cross borders illegally and aimed at militants and at undocumented migrants alike. Heath Bunting walked between European countries in many kinds of settings, passing through forests, rivers, mountains and tunnels. BorderXings Guide is thus a manual written on foot, an act of reportage for others who may wish to cross borders without official documents.” Bunting may well have a new role as our tour guide to a future where we will never know where a border might spring up.

The antiAtlas is also a good source of other artists who seek to question the validity of borders such as Clio Van Aerde’s 2018 Online- A Manifestation of the Human Border, in which she walked the entire length of the the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. She writes: “This project seeks to enlighten absurdities as for instance privileges and barriers encountered in relation to the possession of a certain passport or another. In the larger sense, nowadays, while some people lead progressively nomadic lives as if the borders had vanished, others perceive the exact same borders as impassable barriers.” During the crisis, this has manifested in the Facebook page antiAtlas Des Frontieres, mainly in French, which has documented the new hastily-erected barriers, in this new era of bio-political borders, between France and Switzerland, for example. Different borders, different biologies, different geographies, mean different things to artists.

Shifting geographical realities

In 2018 the Australian artist Sara Morawetz followed the Meridian Line from Dunkirk to Barcelona, following the path of the two French scientists, Pierre Méchain and Jean-Baptiste Delambre, 1792-1798, who first measured the Meridian. It took them six years and they were imprisoned several times en route during the aftermath of the Revolution. They used their subsequent measurements to define the length of a metre. Following the scientists’ route as far as was possible, in ‘Walking From Dunkirk To Barcelona to Measure The Circumference Of The Earth’, it took Morawetz 112 days. She describes her methodology in an interview in The Art Life: “We’re walking the landscape, walking from place to place, roughly following the Meridian line that cuts through Paris. I’ve tried to shape the journey around the towns that the original French scientists visited although this has proved more difficult at certain times than others. We’ve gone slightly off-course to find accommodation, places with food and places that are easy to walk through but the walk is nonetheless shaped by that original journey. Every day – regardless of conditions – we must stop somewhere to take a measurement. That’s done with a GPS receiver taken from two points, a laser range-finder and a constructed target that allows me to measure across distance. These measurements are taken between 300–500 metres, the data from which is then processed in real time…These reports are sent through to the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.” I originally found out about this project in an unusual way, as I live near the Meridian line in SW France during normal times. My neighbour who runs the Auberge opposite sometimes calls me in to translate when his guests can’t speak French. To my surprise his guest one day was an Australian artist walking the Meridien line! I introduced myself as a curator and writer and she told me more about her project on my doorstep. It’s interesting to discover a new artwork entirely out of serendipity.

It is projects like this that may define how we move about in the Europe of the future. With shifting geographical realities and expectations, everyone, artist or not, may have to become more adaptable and take paths less travelled, like the flaneurs, troubadours, wandering monks and pilgrims of the past.

The ‘Future of Transportation‘ group on Facebook.