The making of the maker-farmers (7)

Published 30 April 2018 by Alexis Rowell

Spring has finally arrived at The Big Raise, the (future) permaculture farm and there’s loads to do. Our trainee maker-farmers have windbreaks to plant, cuttings to nurture, fruit bushes to plant. And keep away from water rats…

It’s been the wettest winter for more than 50 years and it was a particularly cold February and March at The Big Raise (la Grande Raisandière), our future permaculture farm in the Perche region of France. So, we didn’t manage to do as much in the garden as we’d have liked. Actually, if truth be told, there’s so much to do we’re feeling a bit overwhelmed. There’s bound to be a relevant Chinese expression about reaching your destination by putting one foot in front of the other!

If you’re going to plant fruit and nut trees, then it’s important to protect them from the prevailing winds. We’re on a hill at The Big Raise so we’re continually buffeted by winds, but the dominant wind is from the south-west (which is odd because I always think of the south-west as being a warm place!).

The main road is also to the south-west, so we get the wind and the traffic noise. Our south-west hedge is a bit thin because the previous owner, Steve, regularly and comprehensively pruned the oaks for firewood. So, we’ve started planting a double-layer hedge using local saplings (hornbeam, hazelnut, wild apple, acacia etc.) we bought from a local nursery. It takes two people an afternoon to clear the brambles (using my new electric chainsaw!), dig holes, plant 20 trees, water them and add manured straw to the surface. So, five afternoons to plant the 100 trees we bought. And five years until they really start generating a benefit!

Steve had already tried to replant this hedge a few years ago, but the brambles took over. When we started cutting them back, we discovered that, happily, some of his trees had survived. Also, the oaks that we thought he’d pruned for firewood to hard, have started to regrow. Nature is so resilient!

Cuttings from our existing fruit bushes have been planted into our new nursery on the south-facing side of the house where they’ll get the most sun. The straw is critical for keeping them warm at night during April and thereafter for keeping moisture in the soil.

Last autumn I took loads of exciting cuttings from fruit bushes at the Norman farm of Bec Hellouin (goji berries, yellow raspberries etc) and put them in the fridge. Unfortunately, I left them in the plastic bags I used to transport them and so they all rotted away! Some things you simply have to learn the hard way!

We also made a mini-greenhouse out of straw bales, some wooden packaging that our kitchen units came in and a bit of plastic sheeting.

I’ve planted a line of willows along the north bank of the canal. It’s easy—you just plant a 1m50 branch and boom, it becomes a tree. They will stabilise the bank. I want to sculpt the south bank a bit, to break up the straight lines, so I’m not planting anything there yet. Mind you the water rats are starting to break up the lines with their games.

But the piece de resistance has to be our first hügelkultur. This German word and permaculture concept means a raised bed containing logs, branches, or even whole trees, which are supposed to provide fertility for future years as they rot down. Some say it’s best to dig a trench and then bury the wood in it. But life is short, so we simply laid our logs in a line and covered them with topsoil from the paths alongside the hügelkultur.

It takes one person an hour to do two metres of hügelkultur like this. It’s really important to cover it with straw to protect the soil from the elements and retain moisture. We’ll plant beans into it in one week when it’s had a chance to settle a bit. The real beauty of this system is that we should never have to work the earth in this bed again.

So, that pond, clean or not?

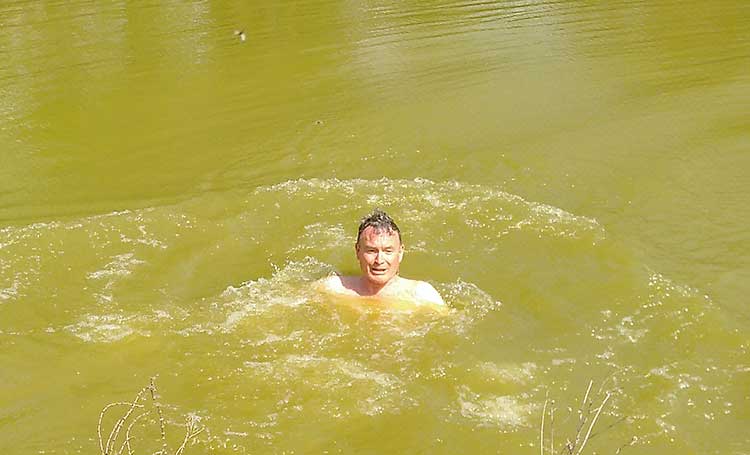

You may remember that we cleaned out the pond last autumn. I’ve ordered a load of oxygenating plants to improve the water quality. And, dressed in my fetching new waders, I also raided our neighbours’ pond for irises which will clean the water.

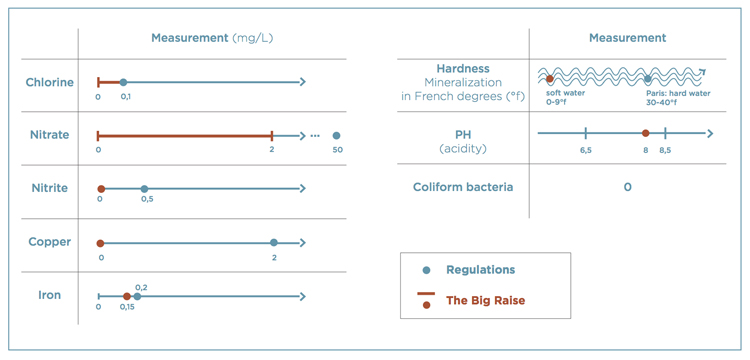

But before we added the plants, we wanted to test the quality of the water to see what’s in it. So we bought a couple of water testing kits—one for before the addition of oxygenating plants and one for after. The two key measures we were interested in were nitrates and coliform bacteria.

A high level of nitrates would indicate that chemical fertilisers are leaking into our water table from surrounding farms. The fields around us are populated by cows so they’re not the risk, but a bit further away the farmers are using chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides to grow a variety of crops.

Coliform bacteria can be found in the aquatic environment, in soil and on vegetation; they are universally present in large numbers in the feces of mammals. While coliforms themselves are not normally causes of serious illness, they are easy to culture, and their presence is used to indicate that other pathogenic organisms of fecal origin may be present. Such pathogens include disease-causing bacteria, viruses, or protozoa and many multicellular parasites.

We were (over-) worried about liquid from the huge pile of horse manure in front of the house leaking into the pond. Or the doings of our three water rats. Or the urine of the ex-owner, Steve, who we caught pissing into the pond the other day—something he used to do all the time apparently!

Table of water quality in the pond:

Thankfully, as you can see from the above table, we found nothing untoward: Our water quality is excellent!

See the previous columns of the maker-farmers

More information on The Big Raise (la Grande Raisandière)