Thingful, a map to navigate the ocean of the Internet of Things

Published 3 April 2018 by Elsa Ferreira

Environment, transportation, energy… Thingful cross-references and searches through data from millions of geolocated sensors in the Internet of Things. We met Usman Haque, its designer.

London, from our correspondent

We first met designer Usman Haque at the Design Modelling Symposium, the international conference held in Paris in October 2017 around the theme “humanizing digital reality”. The cofounder of Umbrellium studio in London was presenting the beta of Thingful Datapipes, the citizen version of his platform for IoT sensors (pollution, climate, temperatures, oceans…).

Launched in 2013, Thingful is defined simply as the first search engine and datavisualization for IoT. Much like the market for connected objects (which is constantly predicted, but has yet to explode), its implementation is a bit more complicated. Ever since, from the semantics of IoT to missing data, there is never a shortage of issues to resolve, Usman Haque and his team confess.

It’s not the first time the designer has worked to open and share data from the Internet of Things. In 2008, he launched Pachube, one of the first platforms in the world for shared environmental data, which was used after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima to visualize citizen measurements of radiation throughout Japan. “We wanted to create Pachube as an open platform where all the sensors could exchange their data directly.” Google acquired the platform for $50 million in March 2018.

Index and thesaurus

Today, in the age of ubiquitous IoT (some 20 billion objects are connected worldwide), there exist hundreds of platforms modeled after Pachube. Open data has even been the subject of national policies. In 2011, the French government created the Etalab mission to develop and maintain a portal of open public data. Other such portals exist for cities (Paris, Barcelona…), industries (agriculture and nutrition…), weather data… “While data exists for a whole bunch of uses and contexts, as well as various types of data, both private and public, it’s incredibly difficult to find,” Haque explains. “You can’t do a search on Google saying, ‘find me a pollution sensor near my home’.”

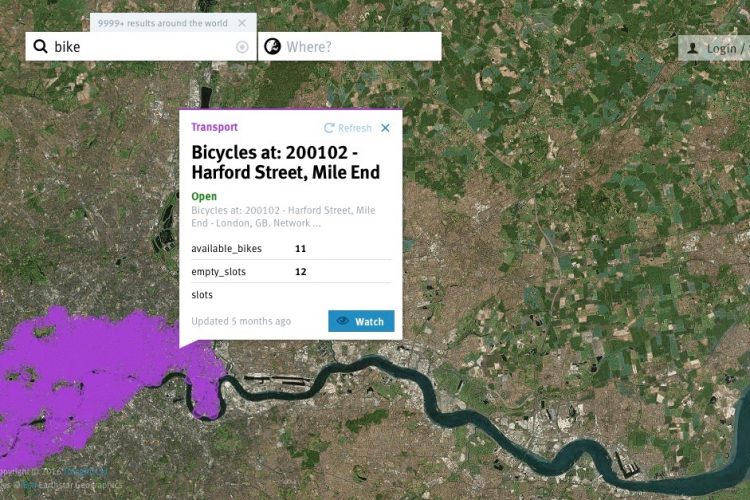

So the ambition of Thingful is to “facilitate searching for connected objects that are already in place”. This initiated the titanic task of indexing hundreds of thousands of data sets, networks and sensors. The Thingful team has created a geolocated repertory of these connected sensors and devices and is working to make them visible on a map. “Often, people write to say ‘Hey, I have a flood sensor, why isn’t it listed in your inventory?’”

Unlike in the case of indexing a Web search engine, the data sets from sensors are not all equivalent. Each connected object can have its own way of capturing data and transmitting it—or not. It’s a matter of dialogue and interoperability. In order to deal with this issue, Thingful will develop a standard for indexing and linking connected objects: PAS 2012 or Hypercat.

With Datapipes, which should soon be released in beta, Thingful is one step closer to a search engine, thanks to its compiled thesaurus of connected objects entered under various terms. “For bicycles, for example,” says Haque, “we say ‘shared bike’ in the UK and ‘bicicletas’ in Spain, whereas in France we talk about the availability of bikes… All these entries for data that we can’t find if we don’t know what they’re called…” If a Spanish user enters the word “bicicletas” in an IoT database for bicycles in Venice, she won’t be able to access the data of shared bikes in Italy, because the term entered in the local database isn’t the same! Datapipes knows not only how to link the terms, it can also make suggestions (like when you misspell a word and Google says “Did you mean…?”). Haque adds that “air quality sensors are often associated with a temperature sensor, for example. We will also offer this data to the user.”

Microchipped animals, earthquakes and bus stops

Thingful claims to index millions of data. But what are we really talking about? “There is really a very wide diversity of connected ‘objects’. Basically, they’re geolocated sensors that generate series of chronological data,” replies Haque. Practically speaking, lots of environmental data: river water levels and flood detectors, meteorological and seismographic data, radiation sensors. Then there is the data from urban terminals: charging points for electric vehicles or dock stations for shared bikes; transportation hubs for connected bus stops or connected vehicles; energy consumption data; animals such as turtles and fish; marine buoys… Only health data is less involved—“The data isn’t available to the public,” says Haque. Not yet?

Giving access to whom, and when?

In addition to indexing connected objects (but not centralizing them, Haque insists), Thingful provides a framework for their exchange. “The promise of the Internet of Things is that each object can talk to all the others,” says the designer. “But in practice, very few communicate with each other, and finding which conversations have value is a very complex technical proposition.” Take a heart monitor, for example, he posits. No doubt you would want your doctor to have access to the data in real-time, but not your family, to avoid alarming them. You might be willing to monetize access to this data to companies, but only at certain times of the day. “In each scenario, the data flow is very different.”

This sharing “à la carte” is one of the foundations of the network. It’s what Haque calls “entitlement”. As most connected objects are private, before an object can be indexed, its owner must give consent. “She could decide to restrict access to her grandmother or only to researchers. She could decide to make the object visible but prohibit access to the data generated. She could decide to give access only to an average of the data, and with a latency time.

Cross-referencing data to give back control

In order to find practical applications for its search engine, Thingful is participating in several European projects: Grow, to monitor soils throughout Europe; Decode, to give back control of their data to citizens; CCAV, the center for connected and autonomous vehicles.

The business model is harder to find. “We don’t believe that the data can be sold anymore,” says Haque, who, after exploring (and giving up on) the lead of the blockchain and microtransactions, is trying to affirm its value as a mediator.

Haque is the first to admit that the Internet of Things, and the associated smart city, have been more often disappointing than promising. “A big part of IoT tends to lean toward an infrastructure of surveillance, especially with these connected objects that generate data and send them to a mysterious database in Silicon Valley,” he says, in the shadow of the Cambridge Analytica scandal.