Who decides, data or us?

Published 3 October 2017 by Annick Rivoire

Do humans have more control on their environment with digital modelling and design tools? The Design Modelling Symposium, in Paris from September 16-20, opened up avenues.

What society do we want? Is technology the solution or the problem? How does one develop while sharing? The international conference Design Modelling Symposium, that brought together from September 16-20 at the Versailles school of architecture (énsa-v), near Paris, a prestigious audience of designers, architects, 3D modelling specialists or data scientists from around the world, had chosen as a theme for 2017 “Humanizing Data Reality”. Guideline of this biennale supported by an interdisciplinary and international platform (of which Makery is a partner): the place of humans and the designer in our digital world.

Although they put these questions to the audience, the speakers did not all come up with a definite answer. Klaas De Rycke (énsa Versailles), one of the organizers of this event, extremely rare in France, summarizes: “The problem is that no architect starts by talking about data, whereas as we have seen, data is essential for projects and their social and collaborative economy.” Could architects and designers, specialists of 3D modelling, primary users of computer aided design also be out of their depth? Could the machine in the cybernetic sense of the word have already won the day?

Data alone is not enough

Not so simple, says Kasper Jordaens, who introduces himself as an “architect who doesn’t work in this field”. This “designer of solutions” explains: “In my environment, the result isn’t necessarily esthetic, not necessarily architectural, it just gives the meaning of data.” But what is data? According to him, data is no more real than virtual, “it means nothing outside its context”. As an example he takes a stitch of jacquard pattern: close-up, it makes no sense, by taking a step back, you make out the pattern of the fabric. What makes the difference today in terms of data, he continues, is that the computer is still as bad for contextualization, interpretation, association of ideas: “it gobbles up data, calculates fast and in bulk,” but as interpretation goes, remains well short of human brains.

With big problems comes big data

According to Carlo Ratti, charismatic director of the Senseable City Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), one needs to go beyond this vision of “above-ground” data. We have already entered the era of convergence between bits and atoms: data is the product of what we do through our digital uses (photos, connections, paths…). The problem is not who manipulates or may be manipulated, the problem is that big data, which he defines as “what you cannot put in an Excel spreadsheet” requires “big Macs”, in other words “network sharing tools.”

“Big data can allow us to have a better overview of our big problems and thus begin to solve them,” he adds, while presenting a few emblematic projects from the Senseable Lab, the “laboratory of urban imagination and innovation through design and science,” such as Treepedia (2016), a worldwide map of the canopy from Google Street View data, or Monitour (2016), data visualization of some 300 electronic waste items thrown into the garbage and previously embedded with GPS trackers by the Basel Action Network (BAN) and the MIT lab, and their incredible post-waste life. Where you can see certain electronic waste items go all the way to Africa, then leave for India, etc. The tracking of this e-waste permitted to visualize concretely the enormous waste and begin to understand the problem, he says. One of the practical effects is that some contributors have stopped using plastic glasses. All this for so little results?

Tomás Diez, the herald of Fabcity and founder of Fablab Barcelona, who defends the idea of the resettlement of production, short circuits, and the citizen element, does not have this naivety. In his keynote (the day before Carlo Ratti’s; we would have liked to see them exchange views on the subject…), the founder of the Fab City network defends the passage “from big data to small data,” in the sense of a personalized and humanized scale of data. He gives the example of El Paquete Semanal, a clever alternative to the censorship to access Internet in Cuba, in this instance an exchange network via a 1,000 GB portable hard disk drive or a USB key packed with content (TV series, information, games, music and other things) that is transmitted from Guantanamo east of Havana with sometimes a week of delay on the global Internet. “The human face of big data,” he says.

Citizen technologies and the reality principle

Thinking that technology would be the answer to all our problems is an illusion, he adds instantly, admitting that the Smartcitizen.me sensor kit project, yet virtuous and supported by the European institutions, is not sufficient in itself: geeks admittedly developed their kit but people did not massively use this sample of citizen sensors. One needs to think about “mediation between people and technologies”. The idea isn’t that everyone starts printing in 3D but rather bring back locally food production, energy and water resources. Starting with concrete experimentations, like the Shower Loop, an open source system developed during POC21 that informs you when you spend more than 3 minutes under the shower and also allows you to recycle the water used! Tomás Diez admits that it is not as simple to “resort to useful sensors in reality”, due to a paradoxical reality (with an explicit drawing).

A little realism facing a complex world that designers, architects and city planners do not master any better than others; that’s what transpired in the 11 keynotes, 45 lectures, 6 workshops and 2 master classes of this 2017 of the Design Modelling Symposium. As if, having their noses stuck in their data, theses big names lacked perspective. The 250 odd participants (of which only a quarter of French people, according to the organizers), debated only a little in the end, due to rather too much “international conference” formats despite a very thorough agenda. Too much information kills the information?

Sharing design

Within the profusion of proposals and project presentations, some trends however emerged. Like this idea of shared design, brilliantly led by the founder of the British studio Umbrellium, Usman Haque. “Why is it important to consider doing with several people? It’s the only way to go through the next decades to decide on our future, even if we don’t all agree on the result, because the present situation is complicated,” he summarizes astutely. “In our democracies, things are being decided more and more by those who do not vote, from Brexit to the last American elections, when on the environmental side, climate change implies disproportionate changes.” A concrete example: if the Thames rose by 5 meters, half of London would have its feet in the water, at 50 meters it would “dramatically change the face of the city,” as one saw recently in Miami.

Facing the challenges of “finance, debt, tax evasion, crypto currencies, can technology save us?” The smart city has only yet proven its efficiency “for the monitoring and the analysis of data.” “Technology is NSA and Prism, leaks and fake news…” So, to give back to the human being its place in the collective decision, Usman Haque demands “mutually assured construction.” “Design together, decide together and act together,” he experiments each possibility. Like calling for participation in the beta version of the IoT sensors shared platform (pollution, climate, temperature, oceans…), Thingful Datapipes. This search engine for citizen shared data on “air, pollution, animals, earthquakes…” is based on his experience in Pachtube (2011), a shared environmental sensors initiative following the Fukushima disaster.

An other way to “act together” on the construction of the city, the Flightpath project in Toronto: with a view to reorganize bus routes in 2011, he had imagined with the artist Natalie Jeremijenko a spectacular and fun event, where inhabitants tested their ideal bus lines using zip-lines and bearing bird wings to find inspiration for their trajectories (the Jeremijenko touch). A way of making us reflect on the concept of a 3D space to redeploy together!

Flightpath Toronto (2011), Usman Haque and Natalie Jeremijenko:

Data and its illusions

Can one go beyond a time-bound episode? Is co-design, negotiation in a project, occurring between the designer and its digital modellings or between the leaders of a project and citizens, more than a new passing fad? Carlo Bailey who came from New York, where he works for the worldwide co-working leader Wework, revealed all too unwillingly to what point 3D design and data sometimes have no other meaning than the famous “wow effect”. While presenting his research based on office size algorithms and data gathered from users to design the ideal co-working space, he finally admits that the aforesaid research confirmed that people preferred a bright office: “We knew that people liked light, but there, we got confirmation. And we discovered that glass partition walls didn’t appeal,” he explains, answering a question from the public on what modelling had “revealed”. As if tools, however powerful they were, had their own limits…

Zack Xuereb Conti from the Singapore university of design and technology attempted to demonstrate it by presenting the results of a research on the introduction of statistics in digital design, or more precisely on “Bayesian inference” in modelling. We put quotation marks because we didn’t grasp everything, except that it’s about using the Bayes theorem, well known among probability enthusiasts, to introduce a little uncertainty in the too perfect modellings of large projects in digital design. Incapable of integrating the random aspect, the unforeseen event, the hazard of contexts in a project, be they geographical, socio-economical or cultural…We did perceive however how the aforementioned presentation left the room of experts baffled. Conclusion of the researcher: “It’s about going beyond the use of tools, entering the black box to control it.”

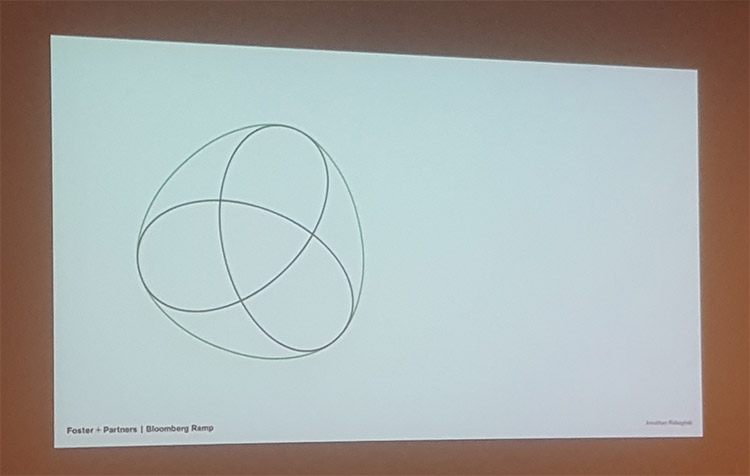

Conversation with data

Concerted design, co-design, shared design are thus also to be shared with the machine, even with data manipulation experts. The architect Jonathan Rabagliati demonstrated it brilliantly with a very concrete project located in the heart of London, where he was in charge of designing a monumental ramp for the European headquarters of Bloomberg signed by the great Norman Foster. With the aid of drawings, diagrams and photos, he tells us about the adventures of a project he first imagined from drawings of the Spirograph, this geometric drawing toy for children in the 1970s, a three ellipse helix he first drew before inserting it to the building.

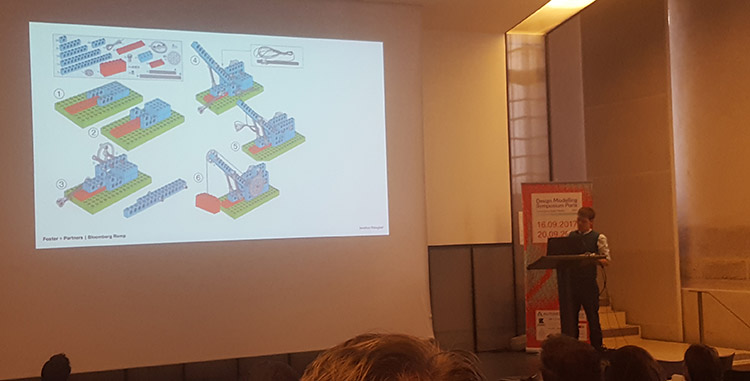

He also talked about the different stages of the dialogue process with the team in charge of the building (the 3D parametric models were not compatible): “We first had to agree on naming, find a common language of inputs and variables, then make the two modelling systems match.” He then shows the drawings in the manner of a Lego assembly plan to exchange opinions with the builders of the steel ramp, which required more than 80 assembly stages…

And finally, the impatience “when the panel steels arrive from Japan, exceptional in their finish give or take 23 millimeters”: It’s then about emerging from the “pure theory” of supports meant to embed themselves in the ramp to within 0.2 millimeters… Who’s making the choice in the project, the architect, the engineers, or the 3D model, to achieve this pure technological prowess, unimaginable without the most current modelling and digital design tools? “It’s a conversation, assures Jonathan Rabagliati. Some things are possible, some are not. The ramp is 30 meters and holds on one hanger midway. That’s the most critical point of this process. We had to try to push and push all the opportunities. The key is always to question the data.”

Real time and sentient city

Dialoguing with data, playing with it, revealing it… Has the advent of big data really radically made a difference? Antoine Picon, professor of the history of architecture and technology at Harvard University, delivered as a conclusion of this symposium one of the most brilliant lessons of putting into perspective our so-called modernity at this time of informational deluge.

Asking “what is really new, a question we should ask ourselves more often,” we have been in the digital era for more than twenty years, modern urbanism based on statistics (thus data) is a “new obsession at the end of the 19th century,” city planners have been reflecting on the intelligent city since the end of the 1950s and cybernetics had already anticipated our contemporary fears on generalized surveillance.

What really is new is real time data, geolocation and the emergence of a sentient city: “When the computer appeared, machines were made to compute; with cybernetics it was machines that think and now it’s artificial intelligence. Nowadays, going digital is a means to express sensations, establish the link between atoms and bits. When you think you feel nowadays, it’s often through a set of digital tools,” from MP3 to SnapMap (the map of the social network Snapchat) or Google Earth… “We are the first civilization capable of tracking millions of people and objects in real time.” A novelty that has transformed the way we live in cities, of which we consider the city planning and also the design: “We went from the sensory city to the sentient city.”

According to the historian, humanizing digital design is showing interest in the sensory experiences of the city where, after having spent centuries managing bad odors, cleaning cities of what was unpleasant to see or smell, “purifying the urban experience,” we are now coming back to ornamentalism, to tactility in a number of urban projects, where attractiveness is achieved through good restaurants and eco-districts with birds and trees. The transition towards this sentient city implies a new form of collective consciousness, closely linked to social networks.

This global consciousness where “we are becoming different as individuals” is much more “radical than the digital revolution,” he affirms. And like any novelty, there is a risk: “In this new world of fake news, you don’t know what you see any more, you can find yourself as in a labyrinth full of mirage where collective sensations may become a delusion.” Collective consciousness would then become collective unconsciousness… The director of Senseable Lab Carlo Ratti has the answer: “We are more and more conscious that we are in the same earth with networks.” Up to us to find the way to live together within the matrix!

The PDF of the acts of the Design Modelling Symposium Paris 2017 “Humanizing Digital Reality” (686 pp, énsa-v & Springer) is made available online for free until mid-October

To take part in the beta version of Thingful Datapipes, send an e-mail to getstarted@thingful.net