The Influencers festival “breathes activism into Barcelona”

Published 17 October 2016 by Ewen Chardronnet

In Barcelona, since 2004, The Influencers festival presents the best of tactical media. The 2016 edition, on October 20-22, has invited Ubuweb founder Kenneth Goldsmith, hacktivist Joey Skaggs and bio-artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg. We met its founder, Bani Brusadin.

The 12th Influencers festival will take place at the Contemporary Culture Center of Barcelona on October 20-22, dedicated to “unconventional art, guerrilla communication, radical entertainment”. Bani Brusadin, founder of The Influencers with Italian artist duo Eva et Franco Mattes, talks about the philosophy behind this iconoclastic festival.

What exactly is The Influencers?

The Influencers is a festival with the subtitle “unconventional art, guerrilla communication, radical entertainment”. It’s not a very precise definition of it, but we want to keep it that way. The festival started in 2004 with Eva and Franco Mattes and myself. We started in Italy back in 2000 with an event called “Digital Is Not Analog”. We were very much interested in those days in what was behind and around all this hype about the Internet. It was the “big revolution”, the “new frontier”, the “information superhighways”—a series of metaphors, and of course those metaphors were invented by someone. But behind that, there was so much more interesting stuff going on. So we decided that we should pay attention to this. We got in touch with the net.art scene, which was quite strong and avant-garde by then. There was also a strong activist movement, partly academic, partly grassroots, blending into each other, with events like Next Five Minutes, the tactical media scene, the mailing-lists like nettime. It was just amazing.

The activist scene in Italy was quite inventive in the 1990s.

Back then, in the late 1990s, my friends Eva and Franco Mattes were very much involved in the Luther Blissett Project, which ended in 1999. Then they started their own artistic career, and at the same time we started the event “Digital Is Not Analog” a.k.a. “DINA”. The title was a bit of a joke, like “GNU is not UNIX”. The event brought together people doing creative stuff with interfaces and the Internet, with activists. So in 2004, we decided to explore the same program here in Barcelona, since we were living here. And if you remember, in 2004 there was no Youtube yet, no Facebook. It was a different world. It was the Myspace age, Napster, and peer-to-peer was the new thing. It was just after the dotcom bubble burst, and companies were just recovering and restarting with new strategies. The Internet was getting more and more commercial and more and more dull. So we thought of starting the project very much based on technology—not as a fetish, but more as a chance to do things that people previously struggled to do and were not really able to. Like alternative ways of connecting people, subverting messages, making fun of power, etc. So The Influencers started like this, adopting a digital attitude in the analog world, and showing how these things are totally intertwined.

So what kind of projects would you show?

Any type of unconventional art projects, trying to deal with the social machinery around media, any kind of media, even showing the Internet as a personal mass media. So we brought to Barcelona a new breath of activism, but then social media exploded and all our reference points went slightly moving. One of the main topics we have always been interested in was fakes, hoaxes, hijacking media, using the smartest strategies and not just counter-information. We were interested in non-rational strategies to counter power, not just the rational, ideological ways of denouncing and demanding.

How has the festival evolved over the years?

It first evolved when social media became an important player in the game. And then the turning point was probably when we invited Trevor Paglen in 2008. He was not yet that famous and was catching up with all the secret information that was out there and revealing the power of infrastructures, the global infrastructure, material and political at the same time. From then on, we decided to dive into these kind of things, and in the last few years we’ve been working on a double track, in a somehow bipolar or schizophrenic visible/invisible way. Because on one side, there is absolute and extreme visibility, in Internet cultures, in what is going on in commercial Internet cultures, but also in non-commercial cultures, since the commercial world is just the tip of the iceberg. So we are interested in how images circulate and how messages are meaningful in such an environment.

So you were interested in Internet memes?

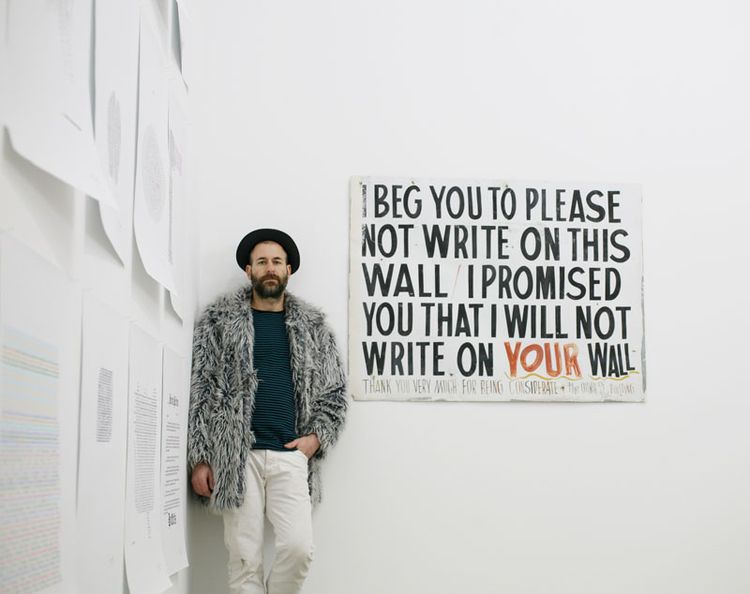

In 2013, we used the Trollface (a rage comic character, editor’s note) as our poster. You could make a mask with it. We also invited David Horvitz in 2014. He did a lot of different projects, but came with one of the few memes created by someone, here with the case of the head in the fridge. Usually memes are not created by anyone, but here it was a lab experiment and you could see the two faces of a phenomenon. Memes are interesting because people pick it up and do something else with it, or use it to say something to their friends. So, someone trying to do something artistic with it is contradictory, because in the chaotic participatory culture, you can’t anticipate what will be next, people do stupid things, it’s one person per minute playing with it. So there is a contradiction here that was very interesting to us. On one side multitudes of people trafficking with images on their own, and on the other side some other people, artists and even activists, trying to sneak into this world and make this world do something else. So David Horvitz was a great example of this.

He also had a couple projects where he tried to infiltrate images into Wikipedia. He made a picture of himself depicting “mood disorder” or depression. So he put his picture on the Wikipedia page, where you couldn’t see his all face. Of course, after some time he got his photo removed, and so he went into a public discussion on this fact. He did another interesting project called “Public Access”, where he started taking pictures in lonely, remote beaches of California, where you could see a little man in the distance, in a corner of the image, and that was him. As an experiment he started to publish these pictures in all the Wikipedia pages of these beaches to see what would happen. After a two-year process, he was banned for vandalizing Wikipedia, but he generated interesting discussions and debates. (“Should we ban this guy? Or is this a valuable contribution to Wikipedia?”) So we were interested in him because he was exploring the boundaries.

And so the other track you were mentioning was extreme invisibility?

Trevor Paglen was indeed trying to put that issue on the table. Infrastructures, control, hidden strategies, ways of controlling masses without letting them know, etc. And of course, in 2009-2010 Wikileaks blew up, and then it was Edward Snowden in 2013. So the other track of The Influencers was thinking about the “Stack” as Benjamin Bratton would call it. Not just the Internet, mobile phones or specific devices, but planetary computation. This huge machine is made by people, and made by infrastructures, and by people controlling these infrastructures. So let’s forget about the Cloud, which is the wrong metaphor, but let’s talk about planetary computation. So in the last editions we have been trying to find ways to talk about this. We’ve been inviting Julian Oliver, with his Critical Engineering Project. We’ve been very much interested in Anonymous, which is a hard subject, and even if usually we do not invite theorists, for that subject we invited Gabriella Coleman, the anthropologist who specializes in that scene.

How did you conceive this year’s edition?

We want to explore this question of extreme visibility / extreme invisibility. On one side, the extreme visibility one, we invite Kenneth Goldsmith, who wrote Wasting Time on the Internet. He did it following the context of an uncreative writing course he gave some years ago at his university, under the same title. This caused a scandal. People were Tweeting: “I am an ace in that, I should not be student but professor!” etc. He then realized that wasting time on the Internet could be done in many different ways, but that the nice thing is when you do it collectively. So he thought he could try it in the classroom. He assumed that our brain may function in a different way, and that we can be creative in a different way. And we need to be creative because the world is so fucked up, we cannot just be paranoid, frustrated, raging or sad. You need to be creative in your life to be proactive.

And for the invisibility?

On the extreme invisibility side there will be, for instance, the non-artist speaker Bill Binney. He had a very prominent role at the NSA in the 1970s and 1980s, because he was using metadata to decipher Russian communications. Not decrypting the messages, but understanding through metadata who was speaking to whom, etc. He was very advanced, so when the Internet came, Bill Binney developed a series of tools, algorithms, based mostly on metadata. But then September 11 came. Bill quickly realized that the government was not just trying to achieve intelligence against terrorism, but was in fact starting a massive surveillance system. He said, “I don’t want to be part of this”, so he resigned and decided to denounce, to blow the whistle about it. He was prosecuted and then became a prominent whistleblower. But Bill Binney didn’t take solid proofs of what he was saying. As far as I know, Edward Snowden was very much influenced by his story, but knew he had to improve his strategy, so he went away with evidences of what he was saying.

And how will these two extremes (visible/invisible) intersect?

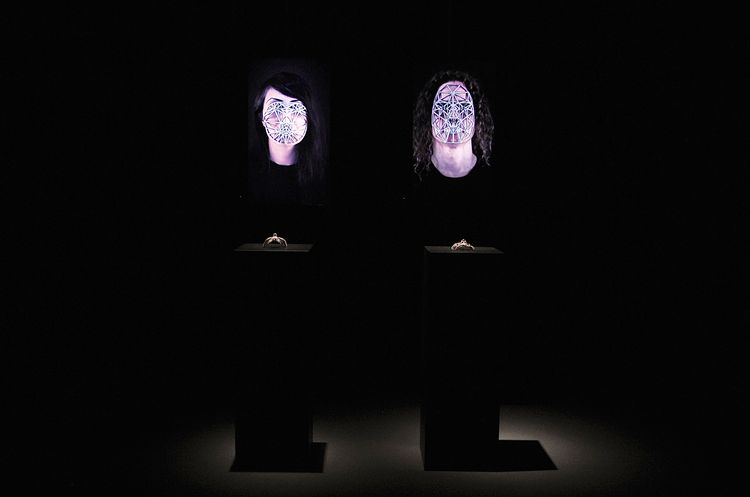

We invited Zach Blas, who is working on biometrics. He made some masks summing up facial data of different people, so-called minorities, queer men, black men, or muslim women, etc. So with these masks, faces are visible for human eyes, but totally unrecognizable by computer eyes, just because they don’t look like faces. We also invited Simon Denny, who is working on these grey areas of planetary computation. For instance, he has worked on specific facts, like the case of Kim Dotcom, the former owner of Mega Upload and now of Mega.com, who was arrested in New Zealand, with some strange connections to the FBI. Simon Denny is touring an exhibition based on the list of all the goods confiscated in Kim Dotcom’s house. People were asking, why should you exhibit all the materials, all the luxury goods seized in the house of a specific guy? Because with these objects, a luxury car, bank account numbers, whatever, you can start to tell stories. And that’s why investigative journalists don’t in a way, academics don’t, activists don’t have time to tell those stories, so here artists can build imagination, and this is really important for understanding the full story.

And what will you discuss with Simon Denny?

He is currently working on blockchain technology, the basis of bitcoin, he just presented that at the Berlin Biennale. He is investigating visions of private enterprises who are trying to invest in blockchain technology. For that he chose three types of companies, think-tanks, or software development companies, who are promoting three different approaches to blockchain technology. One saying that it is the future of community-based society, one aimed at investors saying it is also the future of, let’s say, stock exchange, and one for more political people saying it can help advocacy for changes for good in bureaucracy. So this represents three philosophies, three esthetics, three vocabularies, and in this show he actually made it apparent—not in a Yes Men style, as he’s not hoaxing, he’s not an imposter, but he’s talking like them. And we really want to know more how he actually deals with the idea that basically, those who believe in the blockchain believe that a technology can be a substitute for decision-making, for politics, for trust.

What kind of workshops will you have?

One will be a two-day workshop on network infrastructures led by Joana Moll from Barcelona, anything from submarine cables, to servers, cookies and trackers. Another two-day workshop is on machine learning, with Gene Kogan from the U.S., and he’s going to give hints on how machine learning can be useful for artists and activists. And a third, shorter workshop will be with Heather Dewey Hagborg, on DNA extraction to see how much information you can get from it. And then erase or replace it. Some sort of citizen reverse engineering.

The Influencers 2016, October 20-22 in Barcelona, and archives of previous years