Kyoto Design Lab reconciles thinking and making

Published 1 August 2016 by Cherise Fong

Laser-cut seaweed, lamps made of silk and PLA, drugged flies as miniature models of patients suffering from Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease… D-lab innovates in both education and design: craftspeople, researchers and students collaborate to invent new applications.

Kyoto, special report

“Design is still very underrated,” says Julia Cassim, the visionary British professor of Kyoto Design Lab (D-lab) at the Kyoto Institute of Technology (KIT). “There’s a growing realization that design is not just about esthetics and making things look nice—design is capable of strategic thinking.”

D-lab’s avant-gardist, multidisciplinary and collaborative nature came from the Japanese government’s desire to innovate in design research and education. Since its opening in March 2014, the lab has met this challenge by hosting designers from overseas institutions to collaborate with the university’s students and research professors, as well as craftspeople in Kyoto, while inviting them to interact with the materials of the region and works in the archives.

“In Japan, design education hasn’t really kept pace with the new realities of the computer age, interaction, the fact that their product may be just an interface and nothing more,” Cassim reflects. “Many product and industrial design courses in Japan tend to still be in a 1970s mindset, when there was loads of money and time, and the future seemed endless. On the other hand, Western design education has become heavily concept-based, and not sufficiently technical or materials-based anymore. Here at D-lab, it’s the opposite. You can take materials and think and work through the manipulation and understanding of the material, allied to the concept, so that you can then come up with a new thing.”

If Kyoto Design Lab is only two years old, its mother structure, the Kyoto Institute of Technology, dates back to the Meiji era. The school’s Japanese name better translates its craft origins as a fusion between a college of textile fabrication founded in 1899 and a college of technology founded in 1902.

“Old wisdom, new knowledge”

For this reason, the lab has a particular affinity with textiles and a privileged relationship with those who have been working with them for generations. The laboratory’s generous space is spread out over several rooms, from the open classroom to sprawling studios for crafting wood and metal, which also include all the standard machines of digital fabrication.

In the ancient capital of Kyoto, a city that is both traditional and dynamic, rich in architecture, history, culture and craft, there is no lack of opportunities for collaboration, conservation and reinterpretation. Part of D-lab’s mission is to initiate collaborations between individuals who otherwise might have never met.

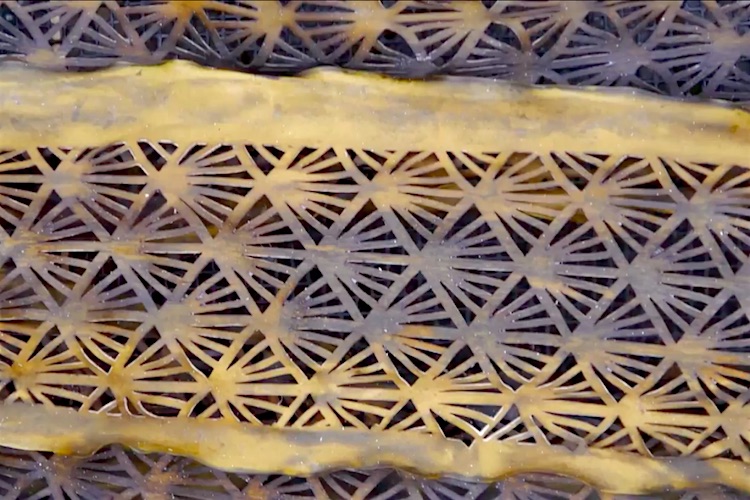

Among the lab’s more recent projects are light fixtures made from local bamboo that integrate laser-cut seaweed from Hokkaido, by designer-in-residence Julia Lohmann from Hamburg University in Germany, aided by a local bamboo craftsman in Kyoto. There are also lamps made from traditional silk reinforced by PLA (polylactic acid), 3D-printed by designer Michelle Baggerman from Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands, in direct collaboration with Masaki Ebara, a craftsman used to tailoring silk into garments for monks and decorations for temples.

Presentation of Michelle Baggerman’s “Woven Light” workshop at Kyoto Design Lab:

Since 1988, KIT’s school of science and technology comprises three departments: architecture and design (which encompasses D-lab); engineering design; materials and life sciences.

In line with its mission to catalyze unexpected collaborations, and always engaged in “inclusive design” (especially for disabled or “invisible” people), D-lab initiated an unprecented collaboration between multi-talented designer Frank Kolkman, inventor of the DIY surgical robot, from the Royal College of Art in London, biologist professor Masamitsu Yamaguchi at KIT, the Center for Advanced Insect Research and the Charcot Marie Tooth research center in Japan. The result is an installation that allows patients of the obscure Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease to test the effects of drug components at home… by observing the reactions of transgenetic flies.

Presentation of the “Design for flies” project at Kyoto Design Lab:

The only minor inconvenience in terms of accessibility, D-lab is located on the suburban university campus of KIT and strictly reserved for D-lab projects. However, D-lab regularly organizes thematic workshops associated with its research projects that are open to everyone and led by invited experts, in order to provoke more mutidisciplinary and strategic collaborations.

“In our increasingly mutidisciplinary world, who leads?” Cassim continues. “We need a methology for advancing interdisciplinary workshops, we need someone to design the framework. What type of person, what discipline is going to lead? I often choose a product designer to lead the team, because they can see anything as product. My view is that designers are really well equipped to be a mediating voice for people who may have very different perceptions of the same word. For example, if you say ‘design’ to an engineer, or to a UX person, or to a graphic artist, they all have different perceptions of what that thing means. Designers have the great advantage of being able to communicate in a language that is immediate and very understandable to people, irrespective of the discipline from which they come.”

In May, leading up to a D-lab project on wearables and smart textiles, Frank Kolkman led a workshop to introduce people to electronics through the medium of paper. Students in design and engineering from KIT and beyond, as well as professionals from various backgrounds, Japanese and foreigners, came together for three days to learn basic electronics. They started by drawing a circuit directly on paper using the conductive ink of a Circuit Scribe pen. Then they conceived a prototype of a three-dimensional paper object that integrated the circuit, followed by more complex functions using Arduino.

Every one of D-lab’s projects, workshops and activities is documented in video, as an immediate and contemporary medium to explain their methodology to an audience beyond academia.

In parallel, D-lab maintains a permanent gallery within the 3331 Arts Chiyoda center in Tokyo, exhibiting their latest projects in yet another context. Currently on view in the capital, the installation Bits of Kyoto Gardens, based on a workshop realized in collaboration with the department of architecture at ETH Zürich, presents the visual and sonic results of an architectural study of the physical spaces of selected gardens and ancient buildings in Kyoto, recorded and 3D scanned, then reconstituted into immersive films that are literally steps away from virtual reality.

Presentation of the project “Measuring the landscape and sound of a Japanese garden” at Kyoto Design Lab:

“Now gradually, because of the maker movement, there’s been a huge reignition of interest in the linkage of making to thinking—and making to concept,” Cassim observes. “In particular, 3D printing has given designers confidence again. Before, if you couldn’t make a model, how did the hell did you show what you wanted to do? This stopped a lot of designers from imagining beyond a certain point. Whereas now, digital visualization and 3D printing have opened up these avenues to iterative prototyping. The heart of any good design is that you’ve got to go through cycles of prototyping, however good the concept. Certainly 3D printing has been responsible, and the whole maker movement engine has made it much easier to imagine and make at the same time.”

More about Kyoto Design Lab