The Nutmeg’s Curse, biopolitical wars, terraformation and extermination. Interview with Amitav Ghosh

Published 12 August 2024 by Pauline Briand

Amitav Ghosh is a fiction and non-fiction writer from India. In his Ibis trilogy, he used opium trade and opium war to address the worldwide impact of colonialism and globalization. He revisits this topic in his latest essay Smoke and Ashes, Opium’s Hidden Histories (2024), in which the opium poppy is granted its own agency. Ghosh’s work focuses on capitalism in the common narrative about climate change and the extinction crisis, in order to delve into their often less visible and more pervasive causes – colonialism and imperialism. From book to book, since The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016), Ghosh has created new narratives that provoke readers to think about these crises from a radically different perspective. With The Nutmeg’s Curse, Parable for a Planet in Crisis (2021), the author examines the resource curse, anchoring it in the 17th century Banda Islands and retracing its path from the Indian Ocean to the Americas and Europe.

Pauline Briand: How would you define the resource curse?

Amitav Ghosh: To understand this we must first ask ourselves what is a ‘resource’? This is a conception that grows out of a certain kind of extractive economy. Before the 16th and 17th centuries, even in Europe people didn’t think of their products as mere resources that existed only to be bought and sold. Everything was deeply connected to ways of life, and they were invested with meaning. Even today, products are not necessarily regarded as mere ‘resources’ that can be reproduced everywhere, as was the case in the colonial world. The Dutch, for example, would never have said to themselves: ‘Well, down in Tuscany they make some nice wines, which could be very profitable. So why don’t we just go down there and kill all the people and grab their land and their grapes?’ This would not have occurred to them because they would have understood that the wines of Tuscany would not have been what they were if not for the specific properties of the land, and the technical knowledge of the people who lived on and cultivated the terrain.

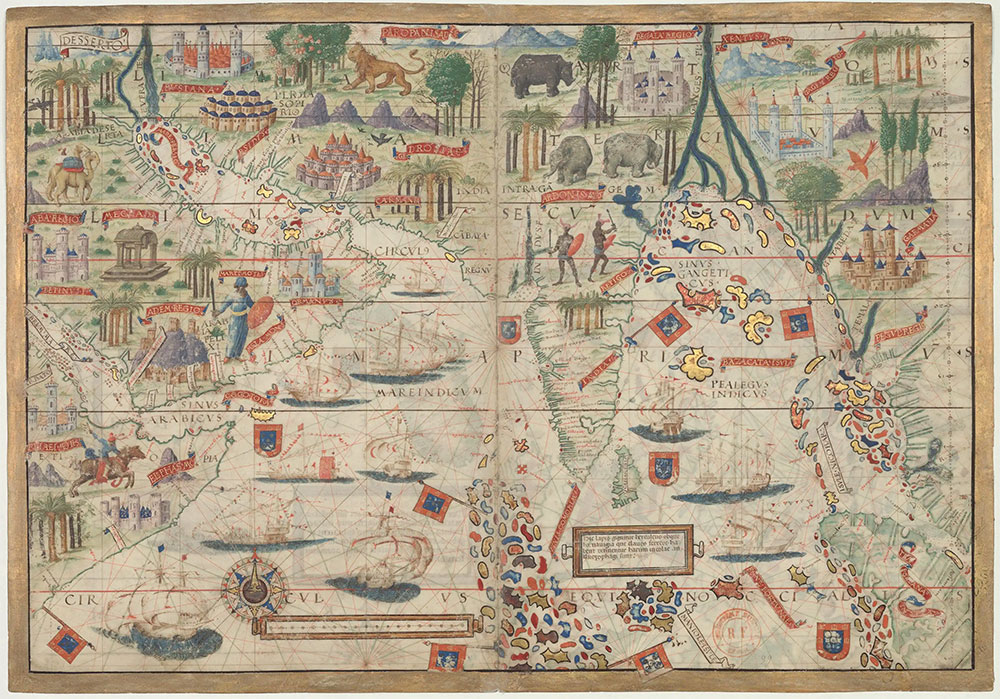

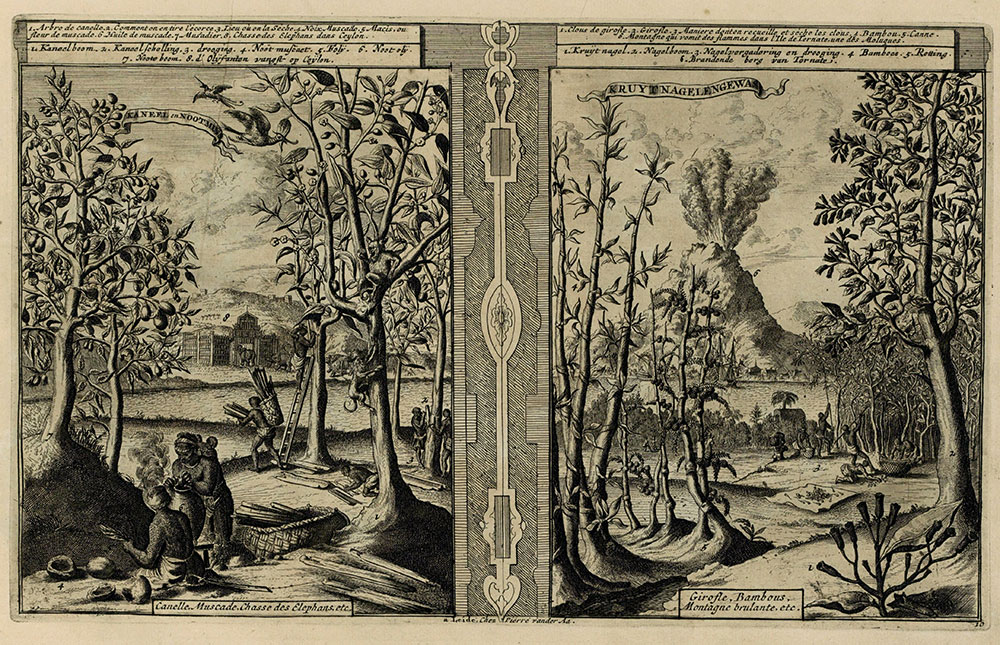

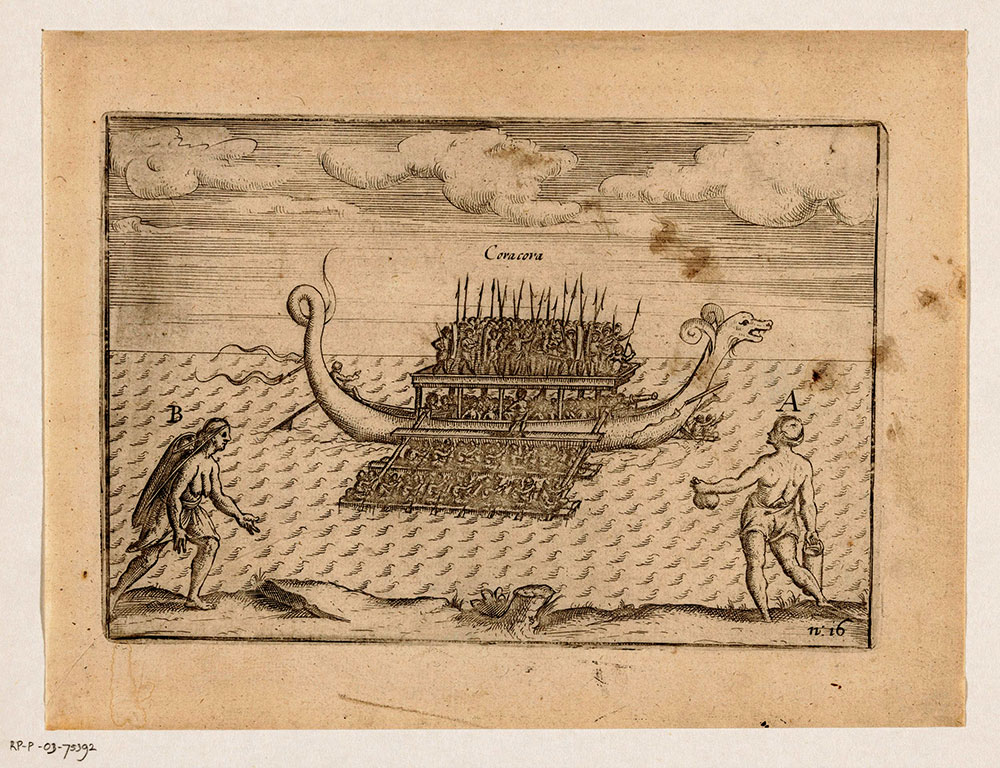

It is important to recall that many, if not most of the Earth’s products were once thought of in the way that we now think of the wines of Tuscany or the cheeses of Parma. Take the nutmeg tree, which produces both nutmeg and mace. Historically the nutmeg tree was found only on the Banda archipelago, which is tiny and very remote. But nutmegs and mace had been circulating around Eurasia and Africa since antiquity, and they had made the Bandanese a prosperous and flourishing community. Over millennia the Banda Islands attracted traders from many distant places: China, India, the Arab world and Africa. Many of those traders spent years living in the Bandas, and they would have been perfectly familiar with the techniques for cultivating nutmeg trees; nor would it have been at all difficult for them to smuggle out seeds and seedlings, to grow in their own countries. Yet none of them ever did that. Instead, for centuries, they undertook the difficult and dangerous journey across the Indian Ocean to the Banda Islands. The reason for this was simply that a nutmeg wasn’t a nutmeg unless it was from the vicinity of the Banda Islands, grown or processed by the Bandanese, just as the wines of Tuscany cannot be considered Chianti unless they are grown by people who are intimately connected with the land and its products.

It is exactly these connections that came to be ruptured by colonialism, as it evolved after the conquest of the Americas. Suddenly everything in the world was up for grabs – botanical species, minerals, and, of course, people as well. So the Dutch decided that they could simply kill or enslave all the Bandanese and take over the nutmeg trade, which is what they proceeded to do in 1621. This was conceivable for them because similar things were happening at the other end of the Dutch Empire, in North-eastern America, where indigenous populations were also being subjected to exterminatory violence. It is in this context that everything in the world is suddenly available for extraction – botanical species, minerals, and, of course, people as well. The nutmeg tree becomes a profit-generating machine to be planted wherever the colonizer pleases, and the people who have nurtured it over centuries become completely expendable. So the nutmeg tree, which had brought great blessings on the people of the Bandas, ultimately became a curse, leading to their elimination from the land. In that sense, the Bandanese were among the first to suffer the ‘resource curse’, and today’s planetary crisis is nothing other than the unfolding of that curse on a planetary scale. In the Andes, millions of indigenous people were killed in silver mines; in the Amazon, similarly thousands died in order to produce rubber for European colonizers. Today many parts of the world that produce oil or gas have been virtually destroyed because they possessed resources – this has happened in the Middle East and in West Africa. In a way, they have all been through the process that destroyed the Banda Islands hundreds of years ago. That was why I centered the book on the nutmeg tree: because this story condenses a much wider history.

Why is it important to give voice to the agencies of the nutmeg tree, nutmeg and mace?

Over the last few years, I have come to be more and more interested in the idea of ‘botanical agency’. My most recent book, Smoke and Ashes is about the history of the opium poppy. With this plant especially it is difficult to completely ignore the feeling that a certain kind of intelligence is at work. In fact, the opium poppy has managed to evade every human attempt to contain and limit it. In Afghanistan, the American army – the mightiest military machine in human history – was essentially defeated by a very humble-looking flower. And of course, fossil fuels, which are nothing other than fossilized botanical matter, have also established a stranglehold on human societies.

Stories are quintessentially the domain of human imaginative life in which non-humans once had voices, and where non-human agency was fully recognized and even celebrated. To make this leap may be difficult in other, more prosaic domains of thought, but it was by no means a stretch in the world of storytelling, where anything is possible. We cannot, after all, expect economists or historians to tell stories in which non-humans are accorded personhood or agency; this is simply not possible within the framework of their disciplines – or, indeed, any academic discipline. But, storytellers uniquely have since antiquity been given a license by society to imagine non-human agency. The Odyssey, Iliad, Ramayana and so on are all replete with many forms of non-human agency. This license has continued into modern times. Melville’s Moby-Dick is a story of non-human agency. Similarly, Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio is basically an imagining of diverse forms of non-human agency. In The Nutmeg’s Curse, I describe how the Dutch writer Louis Couperus represents all kinds of non-human ‘hidden forces’ in his novel. Considering that he was writing for a readership which was, even then, extremely rationalist and materialist, you would imagine that his book would not have been taken seriously. But instead, his novel was celebrated and came to be regarded as a classic. This is one example of how the license to represent non-human agency enables storytellers to imagine various forms of agency. Something similar is at work in popular culture even today. If you look at bestselling books and popular movies, you will see that many of them are about zombies, extraterrestrials, vampires etc. – all kinds of non-humans.

However, in the course of the 20th century, the literary world essentially rejected the amazing license it had been given and came to focus almost exclusively on human subjectivity. The consequent erasure of non-human voices from ‘serious’ literature has played no small part in creating that blindness to other beings that is so marked a feature of official modernity. It follows, then, that if those non-human voices are to be restored to their proper place, then it must be, in the first instance, through the medium of stories.

You establish a continuity between the spice trade routes in the Indian Ocean of the 17th century and the “carbon-capitalism” world that we now live in. Do you think this dimension is overlooked by social-science analysts?

As I see it, the central idea of Anthropocentrism – that the Earth is an inert repository of resources that exists primarily to be exploited by (some) humans – had its origins neither in ‘Nature’, nor in mechanistic philosophies, nor in certain scriptural traditions, as is sometimes argued. Its origins lie, in my view, in the apocalyptic violence that was unleashed by Europeans against their human Others in the Americas and Africa. In particular, it was the violent ‘subduing’ of the people of the Americas that made it possible for elite Europeans to think of everything on the planet as being available for conquest, enslavement and even extermination, as happened in the Banda Islands. In other words, the same violence that made it possible for elite Europeans to think of their human Others as purely material beings, lacking in reason, thought and agency (‘half-devil and half-child’ in Kipling’s words) also made it possible for them to think of the Earth and its gifts in the same way. Both non-humans and human Others were represented as being fit to be ‘subdued’ (a word that recurs often in colonial texts).

It is important to remember that this kind of violence was also directed at European peasants, who, like farmers everywhere, had many kinds of vitalist beliefs. These ideas were as repugnant to elite European men as the so-called ‘paganism’ that they encountered outside Europe, and they waged a very bloody war against these beliefs in the form of the crusade against witches (who were, of course, overwhelmingly women). The same kind of repression continued for centuries, being directed at various peasant movements that insisted upon the sacrality of the land and of the rural communities that lived on it. Nor have these vitalist currents disappeared from Europe. As scholars such as Ernesto di Martino and Jeanne Favret-Saada have shown, they are still very much alive in rural communities – it’s just that they are now carefully hidden.

In your book, the concept of terraformation is central to the colonial project. Why is it still relevant today?

‘Terraforming’ was a very important aspect of the colonization of the ‘New World’. When the Europeans saw North America, especially in the beginning, the forests, the swamps, were perceived as hideous. They thought of this land as ugly and unkempt, and they wanted to transform it completely. Very early on, ecological transformation became a very important part of colonialism. From the 17th century onwards, the English, especially, wanted to transform American landscapes. Within two generations, they managed to make this land into a kind of second England.

But what we are seeing today is the unraveling of landscapes that have been terraformed. It’s the parts of North America that have been most extensively engineered to resemble European models that are the worst affected by climate change. If you look at California, or southern Texas around Houston and most of the Mississippi River Delta, these are the places where the landscape is literally unraveling. It’s clear from the fires sweeping through California that what was done to that land was in fact a sort of profound provocation of the landscape. The same could be said of the southeastern Australian state of Victoria. Many places that were subjected to colonial terraforming are now being devastated by terrible heatwaves and wildfires.

Your book introduced me to the concepts of “slow violence” and “biopolitical wars”. Can you tell us about these processes and the many non-obvious actors who play a part in them?

Ah, yes, welcome to the messy, intricate web of our world. It’s thrilling, isn’t it, to discover these new ways of seeing? Let’s untangle the threads a bit.

Slow violence is a concept invented by Rob Nixon. It refers to the insidious kind of violence that creeps in almost unnoticed, like rising sea levels or the slow poisoning of a landscape by industrial waste. It’s the violence of neglect, of a system that prioritizes profit over people and planet. We often miss it because it unfolds over decades, even centuries. But the damage it inflicts is profound.

Biopolitical warfare is the kind of conflict that occurred during the European colonization of the Americas. A lot of the conquest was actually done through livestock and pathogens, which were sometimes propagated quite deliberately. And that whole thing is very far from over. Those wars of ecological transformation are still going on in Amazonia, because what is at stake is the attempt to turn all of Amazonia into a kind of Midwest. In a sense, climate change can be seen as an extension of the colonial biopolitical wars – it’s now a war of the rich against the poor. It’s very striking how American billionaires seem to believe that climate change will work in much the same way that terraforming did – that is, it will destroy the lands and livelihoods of non-Westerners. But I think they are mistaken. In an earlier era, colonists were able to control various forces, but this is no longer the case. The atmosphere and the Earth itself isn’t taking sides any more – they are striking out against everyone, across the planet.

You quote Ben Ehrenreich: “Only once we imagined the world as dead could we dedicate ourselves to making it so.” Could vitalism be a viable response to the crises we are now facing?

All around the world today we see the emergence of movements that reject mechanistic and extractivist conceptions of the relationship between humans and other living beings. It has even been said that the fastest growing religions of today are ‘Earth-centered’ faiths and practices. As the historian Prasenjit Duara has shown in his book The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future, there are countless such movements in the Global South, and especially in Asia. Yet, it is probably true that many, if not most earth-centered movements are based in the West, and the reason for that is that things have, in a sense, come full-circle: while the elites of formerly colonized countries such as India and Indonesia are racing to embrace settler-colonial practices and policies (which is none other than neoliberalism shorn of the fancy language), many younger Westerners have come to understand that those practices are leading the world – and especially their generation – to disaster. This awakening owes a great deal, of course, to the activism of those who have historically borne the brunt of the suffering inflicted by European colonialism – that is, Indigenous and Black people. It is heartening to see what a tremendous effect the Standing Rock movement has had, for instance. Particularly heartening for me is that these movements are not just narrowly political; they also advocate different ways of thinking about humanity’s relationship to the Earth. They envision the non-human world as being filled with vitality and agency. There is, I think, increasingly a recognition that the mechanistic philosophies that reigned in the West during the centuries of colonization are really nothing other than ideologies of conquest.

The Nutmeg’s Curse reminds me of the economist Joan Martinez Allier’s book The Environmentalism of the Poor, in which he shows how in the Global South, social conflicts often come with environmental conflicts, and that social and environmental justice are intertwined. Is reducing inequality a key priority to address the climate crisis ?

Reducing inequality is not just a priority, it’s the cornerstone of addressing the climate crisis. As you point out, Joan Martinez Allier brilliantly illuminates this connection in The Environmentalism of the Poor. The truth is, the brunt of the climate crisis isn’t borne equally. The wealthy, who’ve profited most from the very systems causing ecological devastation, often escape the worst consequences. Meanwhile, the most vulnerable – indigenous communities, subsistence farmers in the Global South – face the very real threat of displacement, food insecurity, and rising sea levels.

This isn’t simply a matter of geography. It’s about power. Inequality creates a system where the wealthy have a stranglehold on resources and decision-making. They exploit environments with impunity, leaving the poorest to grapple with the fallout. Think of it like a house built on a crumbling foundation. The cracks might first appear in the most neglected rooms, but eventually, the whole structure weakens. Environmental degradation and social injustice are not separate issues; they’re two sides of the same coin. When those most affected by environmental destruction fight back, they’re not just fighting for clean water or fertile land. They’re fighting for a more just and equitable world. The Chipko movement in India, where villagers hugged trees to prevent deforestation, is a powerful example. These are the voices we need to amplify.

Reducing inequality doesn’t just mean evening the economic playing field. It means recognizing the inherent value of those who’ve been marginalized – the knowledge systems of indigenous communities, the sustainable practices of small-scale farmers. We need a fundamental shift in perspective, a move away from the exploitative, extractive model of development that has gotten us here.

So, yes, reducing inequality is absolutely key. It’s about building a more resilient world, one where everyone has a stake in its well-being. It’s about recognizing the interconnectedness of all things, and understanding that a future ravaged by climate change will leave no one unscathed. The fight for climate justice is, at its core, a fight for a more equitable world.

The Nutmeg’s Curse by Amitav Ghosh is available here (University of Chicago Press, editor)

This interview was first published in The Laboratory Planet #6, Planetary Peasants.