More-Than-Planet: Finding new planetary imaginaries and actions

Published 20 February 2023 by Zoénie Deng

From Friday 1 July 2022 until Friday 23 December 2022, the More-than-Planet exhibition at Old Observatory Leiden (NL) curated by Waag showcased five cutting-edge international artists who set off to work in the domain of space. They create alternative visuals, installations and critical narratives to show that other side of the earth. In doing so, the transdisciplinary artworks in the More-than-Planet exhibition aim to spark a discussion about how technologies and the drivers behind their development can help reduce environmental stress.

A conflict will be called, from now on, “of planetary relevance” not because it has the planet for a stage, but because it is about which planet you are claiming to inhabit and defend.

“We Don’t Seem to Live on the Same Planet” – A Fictional Planetarium

Bruno Latour (2019)

This quote from Latour comes from an essay in which he talks about different imaginaries of the planet, such as the planet of GLOBALISATION [1], which started by the imagination of modernising Earth. It is “a sphere of idea that everyone on Earth could develop according to the American way of life, and forever, without any limit.” [2] But the planet does have limits. “75 percent of the planet’s land surface is experiencing measurable human pressure. Another interrelated imaginary of the planet is that of MODERNITY, which demarcates who have never been modern and thus as “Others” and exploitable (see slavery), which also ushered in the age of fossil fuel [3]. The planetary imaginary of globalisation and that of modernity are deeply intertwined with the idea of infinite economic growth and capital accumulation by exploiting certain populations and the Earth, disregarding equality and justice.

In the midst of climate change, rising sea levels, uncontrollable bush fires, extreme weathers, and loss of biodiversity, how can we start to account for these pressing environmental problems that we are living in and with, if our imaginaries of the planet are restricted to these archetypes such as globalisation and modernisation? Therefore, we need new planetary imaginaries that will allow us care for the planet and all its entities including the more-than-human [4] ones differently, which go beyond the scope of economic growth, resource extraction, and human-centric development.

As a response to this urgency, the Creative Europe-funded project More-than-Planet started with an exhibition curated by Waag Futurelab at the Leiden Old Observatory. It was on view from 1st July to 23rd December, 2022. The exhibition explored and questioned what planetary imaginaries we have amidst environmental and other crises; and how through transdisciplinary artistic and social engagements, citizens can creatively and critically use situated data of the space and take concern-driven and care-driven actions to address the pressing planetary issues such environmental crises.

Planetary imaginary: a planet for infinite economic growth?

During the finissage of the More-than-Planet exhibition on 16th December 2022, Nicolas Maigret from the art/research collective Disnovation.org presented their publications and art projects. They engage with the notion of negative commons They engage with the notion of negative commons, which refer to “negative” material or immaterial “resources”, such as waste, nuclear power plants, polluted soils or even certain cultural heritages (for example, the right of a coloniser) [5]. Instead of thinking of extracting resources to fuel economic growth, we need to claim the negative commons such as excessive CO₂ collectively and bring new politics to it. Our first question should be: are we living on a planet for infinite economic growth? And do we want or need infinite economic growth?

In the sci-fi/speculative fiction game Post Growth Toolkit (2020), they question the idea of infinite growth by inviting players to rethink this notion together with other concepts such as inequality, overconsumption, and resource extraction. In their art work Shadow Growth (2021), they query the conventional measurement of GDP, which has never factored in the “social cost of carbon emissions”, pollution, waste, and other ecological damages. How does so-called infinite economic growth matter to us when we situate it within the planetary scenario of inequality among different populations, the damages on the more-than-human species such as animals and plants, and entities like water, air, and soil, and the overextraction of fossil fuels and the consequential excessive CO₂.

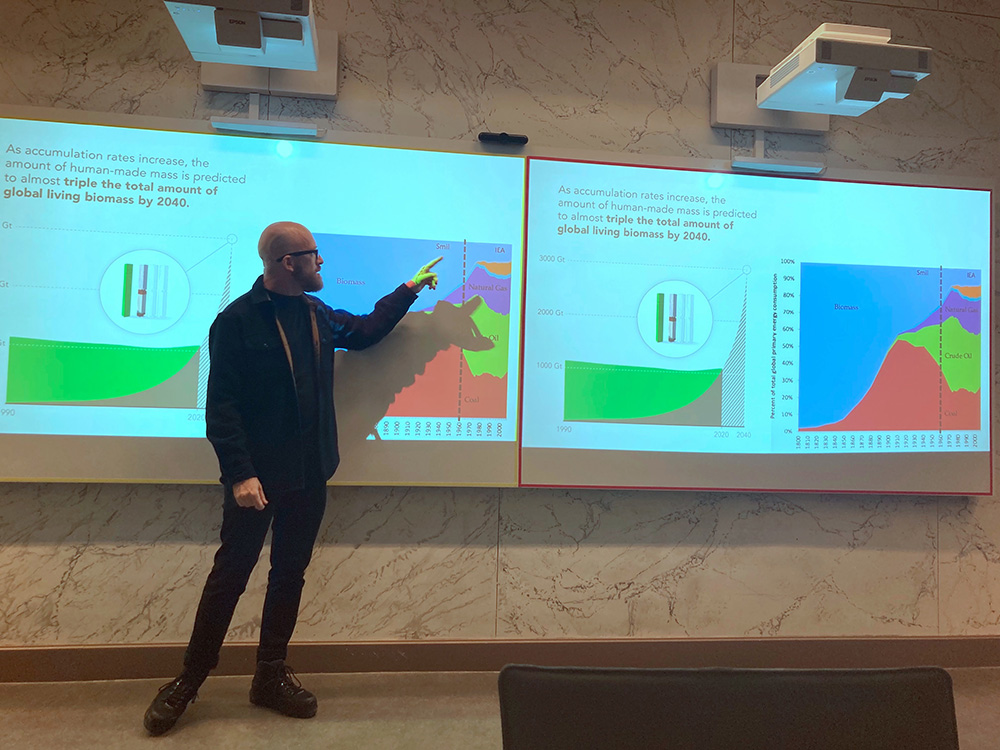

In his talk at the finissage, Maigret quoted from the 2020 Nature article [6] and stated that the accelerated accumulation of artificial mass, such as concrete, bricks, asphalt, and plastic, has surpassed biomass since 2020. In their new project that they are developing within the framework of More-than-Planet, they will look into bio-economics., This is an epistemology “for investigating the socioeconomic system in conjunction with the biological system as a whole and by studying the non-linear interactions between their components and not only the characteristics of the individual components” [7]. This means that the socioeconomic activities of humans are deeply enmeshed with biological activities. To change for the better, analyses and actions should always concern these two interdependent systems together. In line with this, rather than accumulation of capital, Disnovation.org considers economics as the flows of vital energies and matters for human and more-than-human. Within the framework of More-than-Planet, they are going to research solar energy in relation to global algae photosynthesis, focusing on its circulation in the form of energy and biomass within society.

To leave the imaginary of the planet for infinite economic growth, Disnovation.org’s proposition is to concern the planet as a bioeconomical system. They want to research what roles the actors such as solar energy and biomass, play in society, and how we co-exist with these actors.

Concerning planetary crises: speculating, sensing and making it sensible through art

In his well-known essay at 2004, philosopher Bruno Latour proposed to shift critique from inquiring matter of fact to addressing matter of concern. Instead of debunking what is considered as fact, when we critique, we aim to protect and care what we concern ourselves with [8]. In the same line, how can we as humans concern ourselves with planetary crises with critical actions? Some transdisciplinary art projects show the power of speculation, sensing and sensibility, which make the urgency of planetary crises thinkable and palpable.

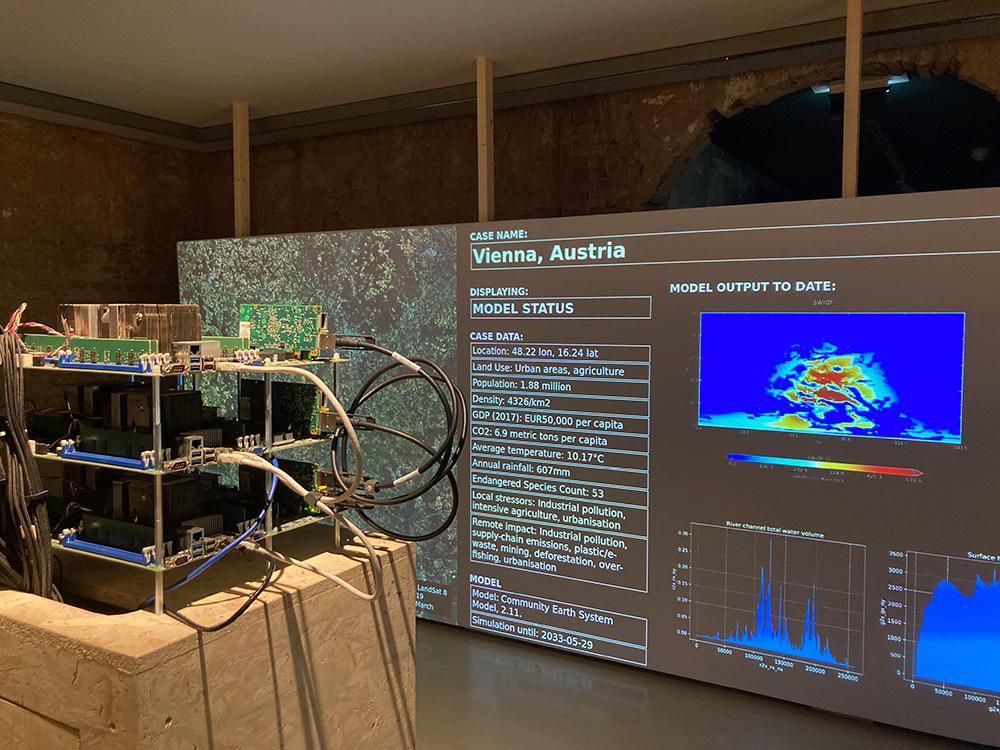

An artwork in the More-than-Planet exhibition in Leiden, “Asunder” (2019) by Tega Brain, Julian Oliver, and Bengt Sjölén creates a fictional “environmental manager” that “proposes and simulates future alterations to the planet to keep it safely within planetary boundaries.” [9] It does so by using climate and environmental simulation technology, a 144 CPU supercomputer and machine learning image-making techniques. The absurdity of the work not only lies in the unacceptable results of this ‘management process’, but also in the impossibility of having such a God-like figure that takes care of the planet.

This speculative art project reminds us not to wait for a “manager” or a powerful geopolitical entity to take action on a planetary scale. Instead, we need take matters into our own hands and care for the planet in situated manners such as acting as citizens rather than consumers in advocating for sustainability.

Another project featured in the More-than-Planet exhibition was Territorial Agency [10]’s Sensible Zone (2022), an off-shoot of the multi-year project Oceans in Transformation, in which the ocean is sensed and made sensible through the collaboration of science, culture, and art. For Territorial Agency, the ocean is a sensible zone. “The sensible zone is the thin, yet vast site of carbon capture and of the life flows and fluxes of climatic homeostasis. It reaches deep into the waters until light can activate photosynthesis, and well above sea level into the mountains, valleys, and ridges of terrestrial life” [11]. Yet it is also the “most sensitive component of the Earth, where ocean meets land, and where technology is weighing onto the complex processes of life planetary regulation”. To sense it, they have used satellite data, and brought together sets of data from above the waves, at the level of waves, and beneath waves. At the same time, they argue, “the ocean is sensing us”. “The ocean is a sensorium. It records in its complex dynamics the transformations of the Earth, and it inscribes its cycles back into the dynamics of life-forms.” [11]

Being architects themselves, Territorial Agency tries to render these visible and relatable in a multi-screened artwork that shows visualisations of data from the deep seas to the atmosphere [12], overlaying Earth-ocean space image. Similar to the manifestation of Oceans in Transformation, where the multi-screened installation shows the visualisation of data of anthropocentric traces and social-political-economic realities such as oil extraction and shipment, slave trade, and refugee migration, Sensible Zone renders visible the anthropocentric activities along the coast, such as the extension of impermeable surfaces on land and building new cities. These images often induce awe in the public. This project, winner of the S+T+ARTS Prize 2021 [13], is accompanied by an e-flux Architecture journal edition, that delves into the slow and invisible processes of the ocean in transformation [14].

Sensible Zone urges us to acquire a planetary imaginary that concerns the ocean as the planet’s biggest living sensorium. We live in it and with it, and therefore we need to be aware of how our human activities and artificial masses are being sensed by the ocean. We need to renovate our respect for the ocean, and for Gaia, “for its (ocean’s) unpredictability and its majestic force, as well as for its hospitality” [15].

Pursuing planetary justice by using data from satellites (and other resources)

During the More-than-Planet symposium on 11th July 2022, Omar Ferwati from Forensic Architecture asked: “how can we change our perspective of the planet from an individual to a community perspective?” The research agency has been conducting investigations on human rights violations since 2010. Recently, some of their investigations have revealed that violence against human communities is often intertwined with violence against more-than-human entities and communities such as the air and rainforest. We can put this into the perspective of the pursuit of planetary justice. Planetary justice here has three dimensions: justice beyond national borders, justice across generations, and justice for non-humans and the Earth system [16].

“If we take a community-oriented perspective of the planet, we have the demand to create the movement that takes stock of development for the community, which means that we have to develop a sensibility also on the ground scale,” Ferwati advocated. This means that to pursue planetary justice, on the one hand, we need to develop a sensibility for the planet as an interconnected whole, and on the other hand, to become grounded on level of community to tackle concrete problems – be it the toxic air breathed by the community of black citizens living in Louisiana, or the violence against the human community and environment in the Amazon rainforest [17].

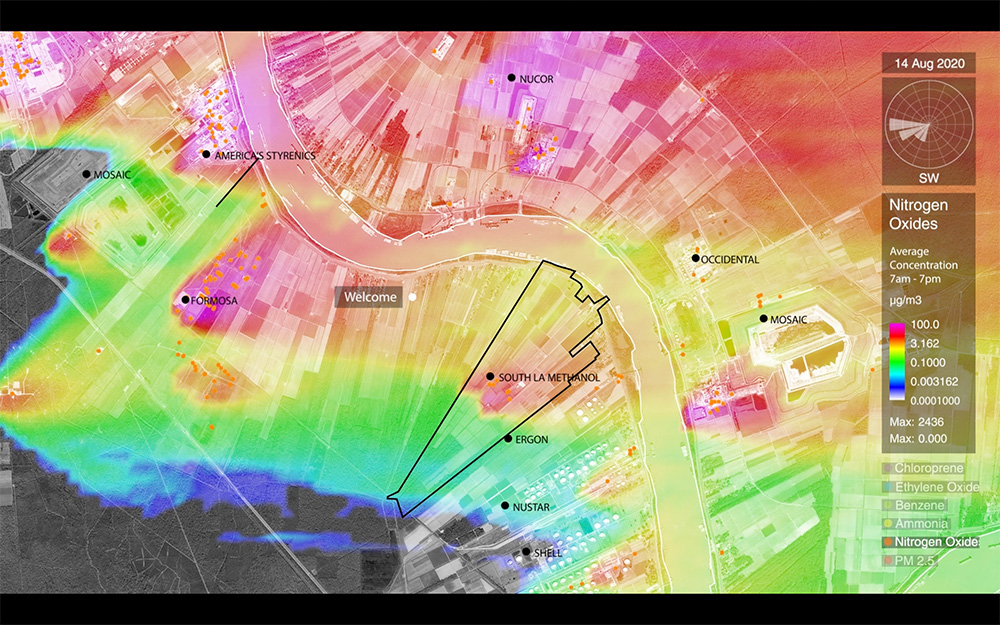

In the artwork “If toxic air is a monument to slavery, how do we take it down?” [18] (2021), Forensic Architecture compares toxic air In the US state of Louisiana to a monument to slavery, as the structural legacy of settler colonialism and slavery remains intact in this state. “Along 85 miles of the Mississippi River, lies a region once called ‘Plantation Country’, now known as the ‘Petrochemical Corridor’.” [19] Over 200 (and counting) chemical factories and oil refineries occupy the formerly slave-powered sugarcane plantations, making the air the most toxic in the US. The air is poisoning the people living there, most of whom are descendants of the enslaved people who had worked on the same land. Activist group Rise in St. James hired Forensic Architecture to search for evidence of airborne pollutants and encroached or wiped-out Black cemeteries. Forensic Architecture has gathered different types of data, including satellite images and meteorological data, and developed a 3D fluid simulation of the pollutants such as PM2.5 and nitrogen oxide. They showed that communities have been suffering from toxic air [20] (see the screenshot below). They have also used historical and archaeological archives to study the plantations and the ways slaves were segregated, tortured and worked to death. With archival materials and recent data, they identified the number of and the locations where the cemeteries used to be. Using situated data, they supported the local communities’ fight for ecological reparation, for the harm caused by environmental racism and capitalism.

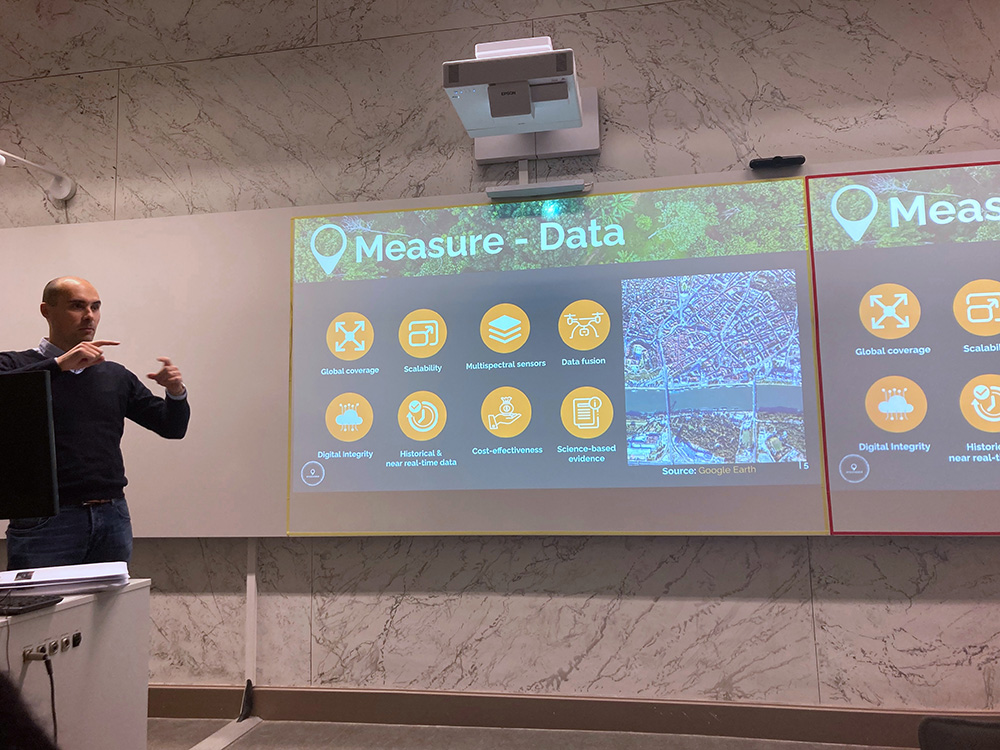

Comparably, during the finissage of the More-than-Planet exhibition in December, Alexander Gunkel, founder of B. Corp Space4Good, has presented a case about the illegal logging detection and prediction project in Sumatra, Indonesia, in which they delivered a near-real-time monitoring platform that can detect deforestation events at a high spatial resolution. Algorithms, drone images, and satellite images were used to understand the ecosystem. The goal was to support land reservation, and to accurately map the deforested areas in order to quickly alert the local authorities. Within the framework of the ongoing More-than-Planet project, Space4Good will collaborate with multiple artists, such as the forementioned Disnovation.org, to synergise creative, critical, investigative, and pragmatic thinking and doing to address the pressing issues of climate crises.

In terms of method and strategy to pursue planetary justice for humans and the more-than-human, both Forensic Architecture and Space4Good are using situated data from satellites and other sources to provide evidence of injustice that is not directly visible. This is to demonstrate how harm is being imposed, what the impacts are, how rights can be protected, and how harm can be repaired.

To conclude, as Miha Turšič, the curator of the More-than-Planet exhibition, remarked during its finissage: before we seek a technological fix [21] for the planetary crises we are in, we need to renew our planetary imaginaries. We also need to publicly discuss insights from critical readings of situated data, and based on that, to rethink future societal and economic models as well as grounded actions. This is already being shown by the practices of artists and B. corps, and their forthcoming collaborations. We also need to ask how data matters, and how active citizens can use planetary data for their concern-driven and care-driven actions to take care of the planet.

Notes

[1] Globalisation and modernity in capital are used by the author Bruno Latour.

[2] Bruno Latour, “We Don’t Seem to Live on the Same Planet”– A Fictional Planetarium, Designs for Different Futures exhibition catalogue, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Walker Art Center, and The Art Institute of Chicago. 2019.

[3] Ibid.

[4] For this term, see the publication More-than-Human. It is a proposition and advocation for “thinking past the centrality of the human subject”, to “imagine networks of ethics and responsibility emerging not from the ideologies of old, but from the messy and complex liveliness around and beneath us”. “The writings included here do more than just question or critique the hegemony of humans over non-humans; they undermine the very possibility of thinking about humanity as autonomous and self-determined.”

[5] Alexandre Monnin, Lionel Maurel, Commun négatif, “Glossaire, Politiques des Communs”, https://politiquesdescommuns.cc/glossaire, access on 20th Jan 2023.

[6] Elhacham, E., Ben-Uri, L., Grozovski, J. et al. Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature 588, 442–444 (2020). See https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-3010-5#citeas. For the full article, see: https://tinyurl.com/469da4ek

[7] Mansour Mohammadian, “What Is Bioeconomics: Biological Economics?” Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, Volume 14, Issue 4, 2003

[8] Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern”, Critical Inquiry 30. 2004. The University of Chicago.

[9] Tega Brain, Julian Oliver, and Bengt Sjölén, Asunder, guidebook of the exhibition More-than-Planet, 2022

[10] Territorial Agency is an independent organization established by architects and urbanists John Palmesino and Ann-Sofi Rönnskog. Territorial Agency combines contemporary architecture, art, spatial analysis, advocacy, and action to promote comprehensive territorial transformations in the Anthropocene epoch.

[11] John Palmesino and Ann-Sofi Rönnskog, “When Above” in the issue Oceans in Transformation, e-flux architecture, 2020. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/oceans/331872/when-above/

[12] See the open-access Ocean Archive: https://ocean-archive.org

[13] See https://ars.electronica.art/newdigitaldeal/en/oceans-in-transformation/. For S+T+ARTS prize, see https://starts.eu

[14] See https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/oceans/

[15] See note 6

[16] Dryzek, John S., and Jonathan Pickering, ‘Planetary justice’, The Politics of the Anthropocene. Oxford, 2018: 68.

[17] Regarding the investigation about the gold mining and violence in Amazon rainforest, see: https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/gold-mining-and-violence-in-the-amazon-rainforest

[18] See https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/environmental-racism-in-death-alley-louisiana

[19] “If toxic air is a monument to slavery, how do we take it down?”, Forensic Architecture, guidebook of the exhibition More than Planet.

[20] To read the investigation and watch the video, you can visit their website: https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/environmental-racism-in-death-alley-louisiana

[21] This is a believe or a myth that can dated back to 1960s. In a 1966 article, atomic physicist Alvin M. Weinberg raised the following question: Are there some types of problems that cannot—or should not—be fixed by technology? Weinberg coined the term technological fix to describe the use of technology to respond to certain types of human social problems that are more traditionally addressed via political, legal, organizational, or other social processes (BYRON P. NEWBERRY, Encyclopaedia https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/technological-fix). Evgeny Morozov and many other have pointed out the folly and trap of technological solutionism. Technology, Morozov proposes, can be a force for improvement—but only if we abandon the idea that it is necessarily revolutionary and instead genuinely interrogate what we are doing with it and what it is doing to us (Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism, 2014).