Helsinki: m/other, or how to explore animal, political, artificial maternities

Published 25 June 2022 by Elsa Ferreira

How to perceive, understand, invent maternities? In 2019, Ida Bencke and Erich Berger started this conversation, which led to “m/other becomings” – a two-year project in collaboration with the Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology (DK), Association for Arts and Mental Health (DK), Bioart Society (FI), Kultivator (SE) and Art Lab Gnesta (SE). On June 9-10, they held a symposium in Helsinki to reflect on these conversations. Makery reports.

The atmosphere is immersed in intimacy. Some 30 people, primarily artists and researchers, gathered for two days at the Helsinki Design School, situated in the heart of the city beyond lush forests and lakes. The theme of their gathering has been brewing deep inside the participants since its genesis.

Ida Bencke, independent curator and co-founder of the Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, recalls how her pregnancy gave her the desire to investigate the relationship that mothers have with others: “I was searching for cultural, literary respresentations, but I didn’t find anything. In children’s books, the mother is often absent or an obstacle to adventure.” While she regrets the dearth of thought-provoking material on the topic of maternities, these two days provided a welcome opportunity to catch up and exchange images, texts, projests, inspirations and poems.

Ida Bencke opened her presentation with a text by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, The Striped Dolphin School, where the author, poet and independent researcher evokes collective maternity (as in a “school” of dolphins): “How can we take care of each other without obligation or imaginary duties? How raising each other up, going into the depths of things, takes time.”

Monstrous body and animalities

One can’t talk about maternity without talking about the body – “the monstrosity of the mother’s body, that leaks, swells, enlarges,” says Bencke. The transformation is visceral and radical, as in fetomaternal microchimerism, whereby cells of the fetus are transferred to the mother, who can carry them for decades. The bodies of men who take care of their children also undergo a transformation: their hormone levels change. Echoing these mutations, Bencke cites Maggie Nelson and her book The Argonauts, asking “how such a profoundly strange, savage and transformative experience can also be its symbol and constitute ultimate conformity”.

“I sit on the ground hunched over the coffee table with a three-month-old baby strewn across my lap,” reads Chessa Adsit-Morris, as if in response, from her preface of the collaborative publication Becoming Feral. “My shirt is stained with rings of breast milk, and my hair sheds constantly. Hormones, I think. […] Becoming-feral involves embodied and performative acts of resistance to the politics of domestication.”

From the various presentations emerges the idea of the enlightened savage. We link our human experiences to our animal companions: hermaphrodite slugs for Margherita Pevere; the transgenerational epigenetic memory of reindeer with Emilia Tikka; the microbiome of goats with Riina Hannula; the creature with the hips of a woman, the jaw of a dog and the legs of a horse, an archaeological find brought to life by Signe Johannessen.

Synthetic life

In contrast to these animal representations, Ionat Zurr took a resolutely mechanical approach. To open the symposium, the artist and researcher from SymbioticA laboratory presented the history of artificial incubation. The first incubator was invented by René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur in 1747 in order to incubate chicken eggs without the hens supplying the necessary maternal heat. The first commercial incubator was developed by Charles Hearson in 1881. “Intensive agriculture considers nature an obstacle to be surmounted,” wrote Jonathan Safran Foer in his book Eating Animals (2009). Then in the 19th and 20th centuries, these same technologies were used for humans. On Coney Island, premature babies were displayed for all to see, as in a freak show. “Baby incubators for sale to hospitals and amusement parks” read one advertisement from that time.

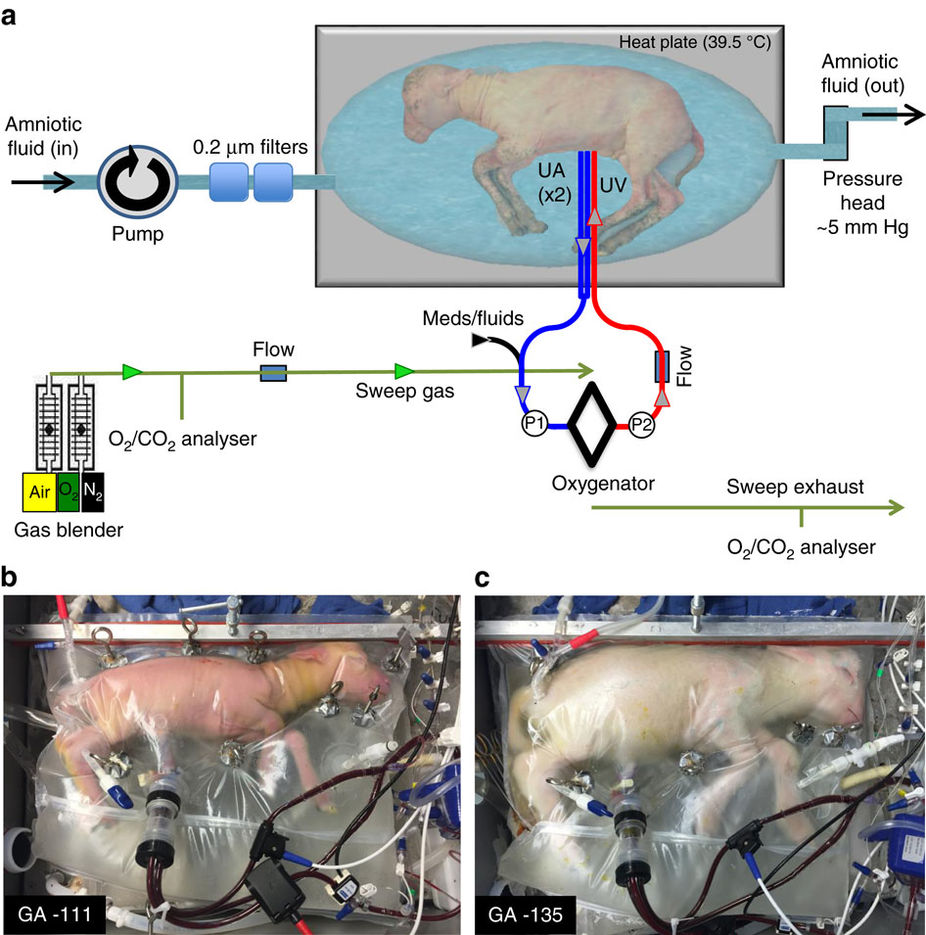

Zurr describes Mycoplasma laboratorium, a synthetic bacteria or “artificial life” developed in 2010 by the researcher Craig Venter and the Nobel Prize-winner for medecine Hamilton Smith. “I created life out of nothing, and its mother is a computer,” Venter allegedly declared regarding his scientific prowess. Then there was Dolly, born in 1996 as the first cloned mammal in history, now exhibited in the technology and innovation section at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburg. In 2015, a device is developed to serve as an artificial uterus by using an artificial placenta to provide the necessary gases and nutrients to a fetus submerged in amniotic fluid.

Meanwhile, Lyndsey Walsh explored the medical gaze on their body and the genetic origin of potential illnesses. In their 2020 essay “Young and Healthy and Waiting to Get Cancer”, they talk about their difficulties of living with the diagnosis of the BRCA1 gene mutation that can cause breast cancer. In Self-Care, they continue to explore this theme by creating a chest binder that is capable of hosting and keeping alive a BRCA1 cancerous cell line.

Semi-life: “life and death are not opposites”

What is life? The concept of “semi-life” came out of “the paucity of words to talk about life,” says Zurr. “In English, there are only two or three words to describe such a complex concept. In comparison, there are probably about 50 words to talk about excrement.” She tells us how, about 30 years ago, she was given dead rabbits with the mission to sample their cell tissue and make them proliferate. That was when she realized that “Life and death are not opposites. From a dead animal, we were going make something that, in a way, would be living.”

Perhaps this is what the Finnish visual artist Pekko Vasantola was thinking as he developed his series of biosculptures: “An attempt to keep my friends alive”. Vasantola took samples of his friends’ body cells, cultivated them in a laboratory and integrated them into artificial tissue. He kept this tissue alive and evolving throughout the exhibition “m/other becomings instalment II”, organized by the Bioart Society to accompany the symposium. It even includes a tutorial: “How to grow pieces of your friends”…

The bioartist and researcher Margherita Pevere elaborated a meditation on hormonal contraception. “A big step for contraception, but also a controversial one: Why should women be the ones who pay for it? Why does the burden of pregnancy always lie with them?” She exposed the political considerations of the pill (“On which bodies was this medical research done? Who has access to the pill?”) as well as the environmental damage caused by ingested hormones – by humans, but especially by animals raised for food that are hormonally supplemented “so that they become pregnant again and again”.

Body politics: decolonizing maternity

It’s important to point out that the maternity explored during these two years refers to the mother not as a woman but as a role, values, an approach. The artist-researchers concur that the notion is not gendered, but eminently political.

In a flowing presentation, the philosopher Tiia Sudenkaarne questioned the major issues of maternity and bioethics, from a queer and feminist perspective. She examined reproductive rights and issues surrounding uterus transplantation (the first live birth after human uterus transplantation was in 2014), the contradiction between the imperative of preserving life and the right to abortion. She questioned the role of the surrogate mother and the transfer of the burden. “Who are they? Do they always do it for money or is it a kind of contribution to reproductive rights?” asked a member of the audience.

“Maternity is an unknown territory,” declared Lesley-Ann Brown, in a story about maternity told through the prism of decolonization. The author of Decolonial Daughter, letter from a Black Woman to my European Son talked about her struggle to access health care as an immigrant in Denmark, her difficult childbirth. “I should have known better than to give birth in Denmark,” she repeated, evoking the increased risks of infant mortality among Black populations in Europe – which resonates directly with the writing workshops for marginalized and minority mothers organized by Ida Bencke and Nazila Kivi – before denouncing “Eurocentric fundamentalism”.

She evoked the journeys of young men seeking asylum, often chosen by their families to go to Europe as the most apt to survive, who ended up dead or disappeared in European countries. Echoing this, Bencke denounced Denmark’s pro-birth and fiercely anti-immigration politics: “It has become extremely clear what kind of bodies are desired for the future.”

“Is there a way to galvanize ourselves around the idea of maternity, the values that we attach to it?” asked Lesley-Ann Brown. “We don’t want to invent maternity as a social practice, since that already exists,” Bencke responded. “We want to take into account marginalized maternities.” And make their representations possible.

Here are a few recommendations for further reading gleaned from the symposium:

– The Great Cosmic Mother, by Monica Sjöö and Barbara Mor

– Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines, by Alexis Pauline Gumbs

– Nightbitch, by Rachel Yoder

More about “m/other becomings”

ART4MED consortium is coordinated by Art2M / Makery (Fr) in cooperation with Bioart Society (Fi), Kersnikova (Si), Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology (Dk), Waag Society (Nl), and co-funded by the Creative Europe program of the European Union.