Ethical Engagement with NFTs – Impossibility or Viable Aspiration?

Published 31 March 2022 by Michelle Kasprzak

“From Commons to NFTs” is an (expanded) writing series initiated by Shu Lea Cheang, Felix Stalder & Ewen Chardronnet. Cautioned by the speculative bubble (burst) of NFTs, the series brings back the notion of commons from around the turn of the millennium to reflect upon and intervene in the transformation of the collective imagination and its divergent futures. Every last day of the month Makery publishes a new contribution of these “chain essays”. Third text by Michelle Kasprzak.

Non-fungible tokens, which can be simply defined as ownership contracts for digital assets, have taken creative communities by storm as an income stream and as a catalyst generating new online communities of creators, outside the influence of curators. The conventional art market as it exists on the highest level serves a predictable roster of ‘blue chip’ artists and wealthy collectors. Given that the art world remains an elite community wherein obtaining gallery representation and making sales is difficult, the possibility for artists to earn their own income from selling ownership contracts for their work issued on the blockchain is a powerful lure. There is also a large and diverse public for art and casual collecting who remain unserved by the elite-level art gallery sector, and online marketplaces selling NFTs can address this gap.

So far it sounds very good: scrappy art world outsiders (David) are earning money doing their own thing outside the elite art ecosystem (Goliath). NFTs have emerged as a vehicle which enables artists to make money outside the gallery system, and provides an impetus to create new networks and online communities alongside the sales platforms themselves. The messy uncuratedness of many NFT platforms such as OpenSea and Hic et Nunc is both an attraction and a challenge. If it sounds so good, what’s the problem?

It’s a major simplification to present the NFT scene as something which merely provides a platform for artists of all levels and would-be collectors without drawbacks. Each sales platform has backers with their own ethical orientations and creative aims. Each blockchain which supports the transactions also has technical considerations (including the amount of energy they consume, something we will examine later) and the ethos of the community which supports it. Just as it is easy to distinguish the ethical and technical differences in orientation between an open source software project run by activist hackers and a closed-source project funded by angel investors, so do these differences exist between blockchains and NFT platforms. Upon an examination of the specifics, enormous differences between platforms and technologies become clear. There are three main issues embedded in the NFT scene which will be examined in this essay, namely the brittleness of the infrastructure, the intentionally-wasteful technology design, and the NFT-as-cash-machine phenomenon and the subversive responses to it. The positive and negative particularities of the NFT are being ingeniously addressed through the work of artists. While these artistic projects may be faint glimmers of hope in an otherwise bleak new reality, they present powerful possibilities for the creation of something actually radical or different. Firstly, let’s look at the underlying structure.

Brittleness of infrastructure

Think for a moment of a website you might have enjoyed visiting several years ago. Take a look and see if the domain name resolves, if the links still work, if some long-abandoned plugin is required. The Web is littered with an incredible amount of digital mulch in the form of abandoned sites and projects. My own first domain name, after I failed to renew it in time, has been squatted by spammers and domain name flippers for more than 20 years. Will any of the blockchains (particularly smaller ones) or their interfacing technologies still be functioning in 5, 10, 15 years? Does it make any sense at all to pursue old school collection models when platforms for digital art are so fragile and subject to change? Already we have witnessed one celebrated platform (Hic et Nunc) rise to prominence, become a popular success, abruptly disintegrate and go offline, and then inexplicably (at least to those who are not following the minutiae) come back online. Each blockchain has its own hype machine (just dip into any Telegram channel for traders in Ethereum, Tezos, Cardano, et cetera) and you’ll find that like fiat currency, confidence in the market itself is the most important factor. Despite it being prudent to expect some level of entropy and instability as the rules of the digital game, it is human to be carried away with success (however you measure it) in the moment, and rare is the person who plans for the long term, when the plugin doesn’t work anymore, the links are all dead, and the hype machines have moved on to the next thing. We forget the word “Friendster” and all the time we invested there, and move on.

There was a first wave of development around NFTs in 2014, which enjoyed limited success, and ultimately those projects don’t function in the same way, or are not in existence today. Harm van den Dorpel, one of the early adopters of NFTs, described how with the early NFTs he created “the token provenance information that ascribe [ascribe.io, a now-defunct platform -Ed.] stored on the immutable Bitcoin blockchain will always remain there, in practice, we have lost access to it, as their web interface to retrieve it was discontinued.” The loss of access meant that the NFT did not effectively exist, and the work had to be re-minted. This example and other fragilities demonstrate one of the issues plaguing NFTs at the current moment, which is confusion around what people own and how one can save and maintain access to their NFTs when technological infrastructures disappear or collapse in future. As many online commentators are fond of saying, one can just right-click and save most visual works being sold as NFTs — so what’s the point? The point is in the smart contract, that public declaration that you have contributed something of value to support the work of an artist. Instead of conceiving of ownership in the way we do today, as consumable and unique objects and experiences, which makes the “just right-click” argument funny, we could instead think of owning NFTs as putting our names on a donor board of a museum, to declare that we have decided that this artist and this artwork are important and we publicly support them and wish to make a small contribution to their popularity and profile. But the average donor board at a museum might last longer than some digital platforms in our fast-moving technological realm. We could therefore ask: what creator-driven, commons-inspired formats can emerge to ensure — or purposefully ignore — preservation?

Wasteful by Design

Knowing that the NFT ecosystem is fragile, we must also reflect on how the very design of the technology may contribute to the degradation of our planetary ecosystem. The Ethereum blockchain is the market leader in the world of NFTs. However, in its current incarnation, Ethereum relies on Proof of Work as the mathematical underpinning. Proof of Work, as described in the initial Bitcoin whitepaper by Satoshi Nakamoto, is “…essentially one-CPU-one-vote. The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, which has the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. If a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes, the honest chain will grow the fastest and outpace any competing chains. To modify a past block, an attacker would have to redo the proof-of-work of the block and all blocks after it and then catch up with and surpass the work of the honest nodes.”

To radically simplify, Proof of Work is a system designed to make an enormous amount of work for CPUs to perform. The security of the system rests directly in how much computing work is required. This computing work does not come without a high energy cost, which is where the controversy around the use of Proof of Work secured blockchains such as Ethereum begins.

In February 2021, Brussels-based artist Joanie Lemercier posted to his website and also started a thread on Twitter, stating that he was shocked to discover the carbon footprint his most recent NFT drop had. He had launched a series of digital artworks entitled “Platonic Solids” which sold out in 10 minutes on the NFT platform Nifty Gateway. He was later informed by carbon footprint measuring organization Offsetra that each artwork in the edition of 53 released 80 kg of CO2, and would continue to expend this energy cost every time the artwork changes hands. Offsetra played a major role in the development of the debate, with Andrew Bonneau, their Advisor — Carbon Markets coming onto chats in Discord servers to introduce Offsetra as “about the environmental impact of the Ethereum network and ways to rectify this, both from a technological standpoint regarding the network’s design and through economic measures to compensate for its associated emissions.“ The concept of carbon calculation played a major role in the ongoing debate as the NFT market grew and artists began to develop a substantial income stream.

Another digital artist, Memo Akten, published a paper to Medium entitled “The Unreasonable Ecological Cost of #CryptoArt (Part 1)” which provided detailed information on the carbon footprint of minting NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain.

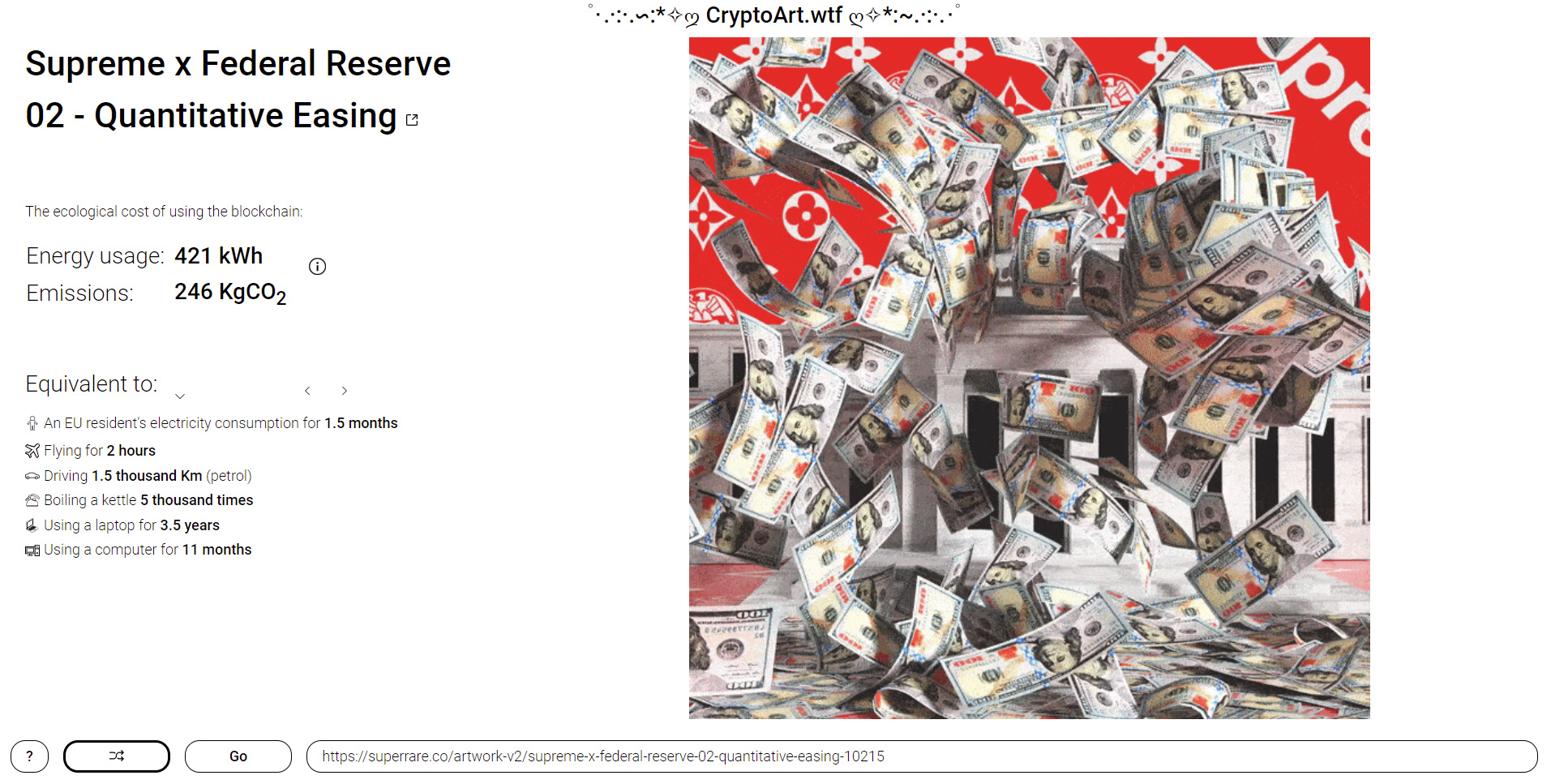

Atken also developed cryptoart.wtf, a website which estimated the carbon footprint of NFT drops. For example, on the site, it was estimated that one SuperRare NFT drop used the equivalent of a 2 hour flight to mint.

Countering Wastefulness

Following the publishing of Atken’s and Lemercier’s respective views on the web and Twitter, the discussion grew to the extent that the format of blog comments and Twitter replies did not truly suffice to capture the range of responses and apparent desire to discuss solutions. The initiative was taken to start a “server” on Discord, an online platform often used for video gamers to take part in live chat while they play. The server was initially called “Eco-NFTs” and was renamed “Clean-NFTs”. On the Discord server, a tentative consensus developed that Proof of Stake blockchains consumed much less energy and therefore was a superior solution, but the sales ecosystem had not developed alongside this. Blockchains using Proof of Stake methodologies, including Cardano and Tezos, had not yet fully developed NFT sales platforms, and hope was expressed that Ethereum would finally move to Proof of Stake, as they had promised for Ethereum 2.0. Preference was still high for established sales platforms using Ethereum, in no small part because of the potential to reach a wider audience and make more money. Some participants in the debate on Discord were keen to try to disprove the high carbon consumption figures presented by Memo Atken, mostly using a “the train is running anyway, so me buying a ticket for the train is no harm” type of analogy to justify their actions.

The commentary on social media continues and from my point of view, is quite polarized between NFT cheerleaders and NFT haters. For example, this Tweet: “hi, thanks for the art share! I’m Doodlemancy and I’ll never do NFTs because I am not a clownshoes dingdong who wants to sacrifice the environment for monopoly money. If what passes for art in the NFT world delights you then my actually semi-competent art will blow your mind.” Here Doodlemancy hits on the lack of environmental credibility that trouble NFTs, and also trashes the firehose of NFT content which is, as many acknowledge, mostly crap.

The Clean-NFTs Discord server grew rapidly from a few dozen people to several hundred, and continues to grow. Initial discussions when the server was launched in February 2021 focused on the core questions posed by Lemercier and Atken’s posts: what can be done about the ecological costs of NFTs? Were “clean” or even “green” NFTs even possible? And if so, how could it be done?

In some ways the arts were late to this conversation. In 2019, a key overview paper by Andoni et al raised the alarm about the energy consumption of Proof of Work algorithms, citing sources that report enormous projected energy costs for Bitcoin transactions, and investigates Proof of Stake as a more efficient alternative (the paper also outlines the possibilities for blockchain to transform the energy sector itself, which is intriguing) (Andoni et al., 2019). The concerns over energy consumption by cryptocurrencies and blockchain transactions were therefore far from new when they arose once again in the arts community in late 2020/early 2021.

But in the arts community, there was a sudden urgency to resolve the question of how dirty this potential new source of money is, as all but the most elite artists live on very little income, a fact investigated in a book by Hans Abbing, entitled Why Are Artists Poor? Abbing argues that the exceptional economy of the arts, wherein most players are impoverished, continues mostly because of the high status that the arts have in society. Abbing also notes that “modern artists don’t starve” because they receive just enough support and benefit from family, side jobs, and the occasional subsidy to float along. Do NFTs offer a way to change this exceptional economy, and redistribute wealth directly to artists?

Artist-run Platform & CleanNFTs

Powered by the Proof of Stake blockchain Tezos, the online platform Hic et Nunc became a phenomenon within mere weeks of its launch in March 2021, in the middle of the Clean NFTs controversy. Hic et Nunc quickly flourished as the risks to artists taking part was low: Tezos are cheap [1] and the fees for minting artworks (“gas fees”) amount to pennies. Compared with the personal risk artists take on when minting on the Ethereum blockchain, where gas fees can cost the equivalent of hundreds of Euros, the Tezos ecosystem offered an entry point for NFT-curious artists with much lower personal risk.

Hic et Nunc grew and artists began to earn money and amass followings. Artist Matthew Plummer-Fernandez described it as a platform which provides artists with “an inexpensive and easy way to trade with one another for next-to-nothing fees and profits in tezos that beat low paid jobs. It’s a platform with integrity and purpose, rather than glamour and exclusivity, and nothing about it is superfluous – its minimal design features are the bare essentials of what it needs to operate as a site for trading NFTs.” Hic et Nunc grew into a community with thousands of artists taking part and posting NFTs of their work for sale, a Discord server with active discussions in multiple languages, and events such as #OBJKT4OBJKT [2] wherein artists traded OBJKTs for free or very low fees. A sense of mutual support and aid was being fostered, and in some cases life-changing support was being provided for struggling artists. Hic et Nunc also tried to address the problem with brittle infrastructure by using IPFS, a protocol and distributed, peer-to-peer file storage network. With big, expensive drops happening simultaneously on closed, invite-only platforms, the mutual support and aid happening on Hic et Nunc became the closest thing the NFT world might have had to a commons.

At the core of the debate around the superiority of Proof of Stake systems was the environmental question, or at least that was how the dialogue was unfolding among concerned artists on Discord and Twitter. Scholars have noted the difficulty of measuring carbon footprint accurately, and it is important to remember where the notion of the carbon footprint came from: it was developed by fossil fuel giant BP to transfer responsibility onto individuals and away from companies. While the Hic et Nunc platform blossomed and grew, the debate raged on the Clean-NFTs Discord server and elsewhere online. Questions of measurement and how much carbon exactly is used in transactions were raised; Memo Akten’s cryptoart.wtf carbon calculator for NFT drops was taken offline after artists said they felt harassed online by users of the platform. Artists on more exclusive, invitation-only platforms such as Foundation which use Ethereum began to pick apart at the math and forms of measurement to suggest that what they were doing was actually not that bad, in the grand scheme of package holidays and using your diesel car to commute.

What began to emerge, however, was a strong picture of a general turn by the creative community towards a disbelief in offsetting and an understanding of the trouble with greenwashing [3]. Some reactions to the debate on the energy cost of NFTs were predictable: charity NFT auctions which would “benefit the planet”, involving tree-planting offsets (which are of dubious value) while the auctions themselves generate high levels of CO2. One of the crucial aspects of this debate is typical of the wider climate crisis debates, which is the desire to maintain life as we know it with all its comforts by offsetting away any guilt about needlessly consuming resources, contrasted with the understanding that we should consume as little as possible in the first place. The NFT boom has disheartened many, as huge sellers such as the infamous “Everydays” piece by Beeple auctioned by Christie’s are bought not by art collectors of note but by crypto speculators — perhaps even Beeple himself. The urge to do the right thing in the first place — despite some Proof of Work apologists — and the booming ecosystems not just on Hic et Nunc but also other Proof of Stake-powered platforms under development show promise.

Beyond “get rich quick”

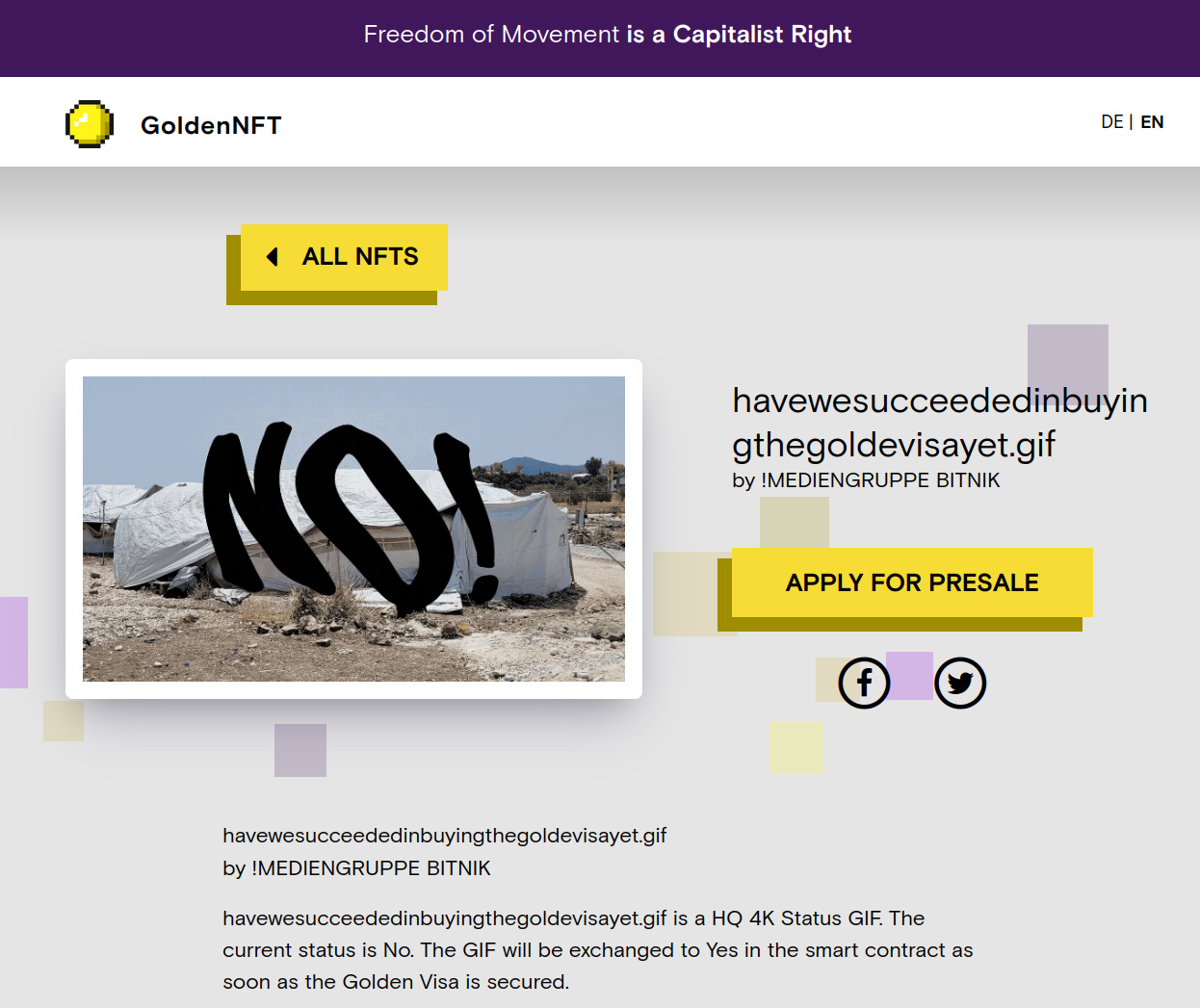

Further evidence of a positive future exists in the form of ongoing subversion of the NFT as a cultural moment, a method, and a way of earning money despite the possible cost to the environment. When closing access to the cryptoart.wtf site in March 2021, Memo Atken noted: “CryptoArt is a tiny part of global emissions. Our actions in this space is a reflection of the mindset that we need in our efforts for larger-scale systemic change.” When considering the potential of NFT projects to contribute to systemic change, projects such as GoldenNFT.art by the Peng! Collective are hugely inspiring. Noting that “Freedom of movement is a Capitalist Right”, the collective is auctioning NFTs to raise the amount of money required to purchase a so-called “Golden Visa”, the scheme that allows one to buy a European passport as an investor of significant sums of money. Golden Visas are usually obtained by the rich who simply wish to buy a European passport, but in this example, the group is raising money to buy a Golden Visa so that an asylum-seeking family can be rehoused in Europe. In one of the NFTs for sale, !Mediengruppe Bitnik has created a dynamic piece, which displays the status “NO!” over an image of what appears to be a tent in a refugee camp, and when the sufficient amount of money is raised, the smart contract will change the status GIF to “YES”.

While this particular project does not address the climate crisis, and the NFTs are minted on the Ethereum blockchain, this project still resonates as an example of how a creative choice was made to engage with one of the most popular cryptocurrencies in order to facilitate its goal, which focuses on transcending borders and exploiting the hype around NFTs to address this. As the aim of the project is to quickly earn a large sum of money to achieve a specific social goal, it makes sense to opt for Ethereum due to its popularity. Small trades between communities of artists in the spirit of mutual aid make a lot of sense on the Proof-of-Stake Tezos blockchain, wherein one can also feel good about using the least energy possible.

Another recent example of subverting the NFT-as-cash-machine ethos is the Balot NFT proposed by the Congolese Plantation Workers’ Art League (CATPC) together with Dutch artist Renzo Martens. Martens set up the Institute for Human Activities, a white cube museum, training programme, and critical anti-colonial project on the site of a former Unilever palm oil plantation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Institute created a training programme which enabled former plantation workers to retrain as artists, who then formed the CATPC. Martens has used his art world credibility to great success, raising the profile of the CATPC members and showcasing their work in prestigious galleries worldwide.

Interestingly, this is where the firehose-of-content spirit of NFTs, and its huge creator base which operates outside of the art world elite, depart ways. Martens and CATPC have moved to create the Balot NFT, an NFT of a sculpture of a particularly brutal colonial figure, in order to raise enough money to buy their own land in Congo back. The museum in the United States which owns the sculpture of Balot has reacted negatively, and now a conflict ensues. Again we have a battle of David and Goliath: the Congolese who have been robbed of their land, this sculpture, a financial future, everything — and the elite art world institutions and private collectors who earn money on every speculation. If NFT-as-cash-machine is going to be one of the many realities of the scene, why couldn’t it be to buy actual land back for those who rightfully deserve it, instead of empty crypto speculation?

This project also provides an inverted reflection on a real problem plaguing NFTs. Many artists have discovered to their shock that their works or their social media posts have been captured by others, and mimicked, precisely copied, or simply screenshotted and turned into NFTs which have then earned money for the content poachers. By making an NFT of this sculpture, the members of CATPC are attempting to apply corrective justice by taking the image of the sculpture that they were unable to own or even loan from the museum now holding it, and making it into an asset they can share and sell.

Blossoms in the Wasteland

In this rapidly-evolving era of NFTs, there is an opportunity to simply piggyback on the crypto-hypeor to exploit the fundraising potential of NFTs to make strong critical interventions, such as GoldenNFT in the space of migration, and to direct funds to just causes as with the Balot NFT. Exploitation, speculation, and a lingering worry around wastefulness and greed will persist in the field, as these qualities are an intrinsic part of the crypto scene. As in the introduction to this series, Felix Stalder spoke of the way that the commons can become enclosed by malevolent interests, and it is easy to see how the positive possibilities of NFTs and smart contracts can also be easily used for greed or theft. Artists and activists can play a major role in continuing to use NFT sales for positive social change and redirecting money to places where it is needed. The communities of mutual social aid referenced by Plummer-Fernandez, and the radical work by CATPC/Martens and the GoldenNFT group provide leading examples of what can be done. What exists here is not a wasteland, but a battle for a new kind of commons itself. If the field is abandoned to greedy and dubious actors, the sharp critique of NFTs as wasteful and pointless will become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Notes

[1] XTZ trading for 3.20 EUR, and 1 ETH trading for 2831.02 EUR at the time of writing

[2] an OBJKT is Hic et Nunc terminology for an individual NFT

[3] Something to watch in this space is the forthcoming Anti-Offsetting Primer, a toolkit being developed by Luiza Prado which will provide “useful and imaginative alternatives to offetting for art workers, artists and communities“.

Read the texts in the series:

From Commons to NFTs: Digital objects and radical imagination by Felix Stalder

Can NFTs be used to build (more-than-human) communities? Artist experiments from Japan by Yukiko Shikata

Ethical Engagement with NFTs – Impossibility or Viable Aspiration? by Michelle Kasprzak

The Real Crypto Movement by Denis ‘Jaromil’ Roio

My first NFT, and why it was not a life-changing experience by Cornelia Sollfrank

It is getting harder to have fun while staying poor by Jaya Klara Brekke