Biomaterials, Fermentation and Kombucha at Nimes University

Published 16 February 2022 by Maya Minder

A two-week Bachelor of Design class at the University of Nîmes (France), initiated by artist and academic Lucile Haute (Ph.D.), experimented with biofabrication using kombucha cellulose, novel material. The experiments use a holistic approach to guide students in a Do-It-With-Others (DIWO), hands-on practice along with other artists, designers, engineers, small businesses, NGOs, and scholars, teaching them how to use sustainable biomaterials in their business.

Kombucha, a sweet beverage often found in organic food stores or vegan hipster restaurants, has been around for some time on our horizon, with the promise of probiotic well-being, and with small businesses supporting its local production. Known as an ancient rejuvenation drink originating in the region of China and spreading along the silk road, it is prepared by fermenting tea and sugar. Kombucha needs a starter culture for initiating the fermentation process. A symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, popularly known as Scoby, serves to endlessly reproduce the beverage using a continuous brewing method. By abuse of language (considering that the symbiotic culture populates all the liquide medium, not only the cellulose), the Scoby is the term used to qualify the eerie, squid-like patch of mostly slug, a strange gelatinous pellicle that floats on the surface of the liquid. Scoby has now started to attract the attention of many. Kombucha Scoby reproduces layer after layer, like a perpetual machine, almost without any effort, needing only tea and sugar, and no heat. For those who brew it at home know it from peer-to-peer sharing with friends and neighbours. Quite often, however, Scoby ends up on a compost pile, and we don’t know what to do with it.

Only recently designers have become aware that Scoby can be used for creating biocouture, or new materials and objects made from it. A two-week workshop that started tinkering with Kombucha Scobies as bacterial cellulose also encouraged participants to research and create ideas for its industrial application, while learning about circular economy, sustainable production, the art of fermentation and possible ways to reduce plastic-based materials.

More-than Human Anthropology Approaches for Design Studies

Combining pedagogical and research issues, this workshop supported by the design research laboratory Project is part of an approach aiming to de-anthropocentrate design and care, to “build a committed and eco-responsible “living together” that includes the plant, animal and fungal kingdoms, up to the communities of bacteria in our biotopes” (1).

Initiator Lucile Haute, artist and lecturer in Design at University of Nimes, invited the most recent experts that are working in this still very experimental field: Vivien Roussel from the NGO Design studio thr34d5 that is promoting open source recipes on kombucha as bioleather; Vivant Kombucha, a local micro-brewery from Paris; Pascal Dhulster, Professor of applied science of food processes, who gave insights into the industry and the general challenges of working with biomaterials based on fermentation and with products with a finite shelf life; bioartist and curator Maya Minder from International Hackteria Network, who introduced the art of fermentation (and is the author of this article); Alexia Venot, a designer and educator working with biomaterials; and the sustainable fashion designer Corinna Mattner who introduced the fair fashion movement of Fashion Revolution. In addition to the stakeholders, there were two guests: Jeanne Mainetti (PhD candidate in sociology working on macker and fablab culture) and Charles Raberin (shoe designer interested in biomaterials). This diverse group of people brought together the collective research and mutual inspiration that have been invested into the subject of sustainable biomaterials.

Besides these vivid contributions, the theoretical background was planted by readings (Noma s Fermentation guide, Food Phreaking Issue 03 Gut Gardening by The Center for Genomic Gastronomy, Mendini’s “An deux mille : de quel côté être ?”, Victor Papanek, to mention some of them) and screenings (Symbiotic Earth. How Lynn Margulis Rocked the Boat and Started a Scientific Revolution, John Feldman, 2019; Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival, Fabrizio Terranova, 2016).

A Table not Yet Fully Digested

Kombucha is one of thousands of products of fermentation that includes, among other, beer, wine, cheese, soy sauce, tempeh, and tepache. This big plate of fermented products has served humanity since ancient times with microbial and enzymatic transformation of food into probiotic and tasty, umami-rich condiments (1). Lactobacillus sours vegetables and changes their flavor into umami-rich mouth watering dishes. Yeast transforms starches and sugars from fruits and cereals into alcoholic beer and wine. Without fermentation there would be no alcohol and no processed vitamin sources that helped sea-voyagers combat scurvy in old times.

Some contemporary authors claim fermentation not only enriches our food with nutrients but also makes them less toxic and contributes to a healthy gut (2). The fact is, humans are entangled with the microbiome of their guts. For example, an adult human carries more than 0,2 kilograms of microorganisms within himself, the ratio between human cells and bacterial cells is 1:1 (3). Fermented food lies somewhere between raw and cooked food. It is externally predigested by enzymatic denaturalisation of plant-proteins and fibers, similar to the process of cooking but without the addition of heat, thereby using no energy. The microbes do the “cooking” for us. Homemade fermentation as a cooking practice bridges this thin line between human control and manipulation, and creates, for those curious, an all-senses encounter with the invisible world of microbes through the transformation of food.

Kombucha Biofilm as a Novel Biomaterial

Kombucha pellicules are biofilms, that is, a cellulose material entirely produced by microorganisms coexisting within a fermenting liquid. Recently it has attracted the attention not only of a larger community of enthusiastic kombucha brewers but also of scientists and designers. In certain fermentations such as milk- or water-kefir as well as in vinegar production, biofilms occur as a natural, polymer-based material naturally produced by the coexisting microbes that chemically produce a film on the liquid’s surface to protect it from harmful bacteria and fungus during the acidity buildup phase while also creating an anaerobic environment (4). This film is called bacterial cellulose and this is where the story of biomaterials starts; applying a circular economy approach, one can benefit from the non-energy consuming growth of the material. In the field of biomaterial design this has been made popular by bio-couture pioneer Suzanne Lee or Mara Vitruft from TextilLab Amsterdam or Clara Davis from FabTextiles, who have proposed ideas of replacing plastic-based materials and animal cruelty free biomaterials. With the advent of the Anthropocene, one of the biggest challenges facing us is how to use, replace, or upcycle petroleum-based products. Kombucha and its ability to produce bioplastics promises a bottom-up approach that can be sustainable and even doable by anyone at home.

thr34d5 – Kombucha Applied Research Project

To start the workshop, Vivien Roussel, artist and maker from thr34d5 NGO Design Studio, gave an introduction to their wide field of applied research and design, focusing on kombucha’s cellulose material characteristics and use in fashion and textile design. As described on their website, thr34d5 are fostering social inclusion by conducting design research and combining craft with open source, designing processes, object, installation, architecture, educational program, as well as artworks. thr34d5 specializes in growing kombucha as a biomaterial and makes their recipes available freely on a wikifactory under karp – Kombucha Applied Research Project .

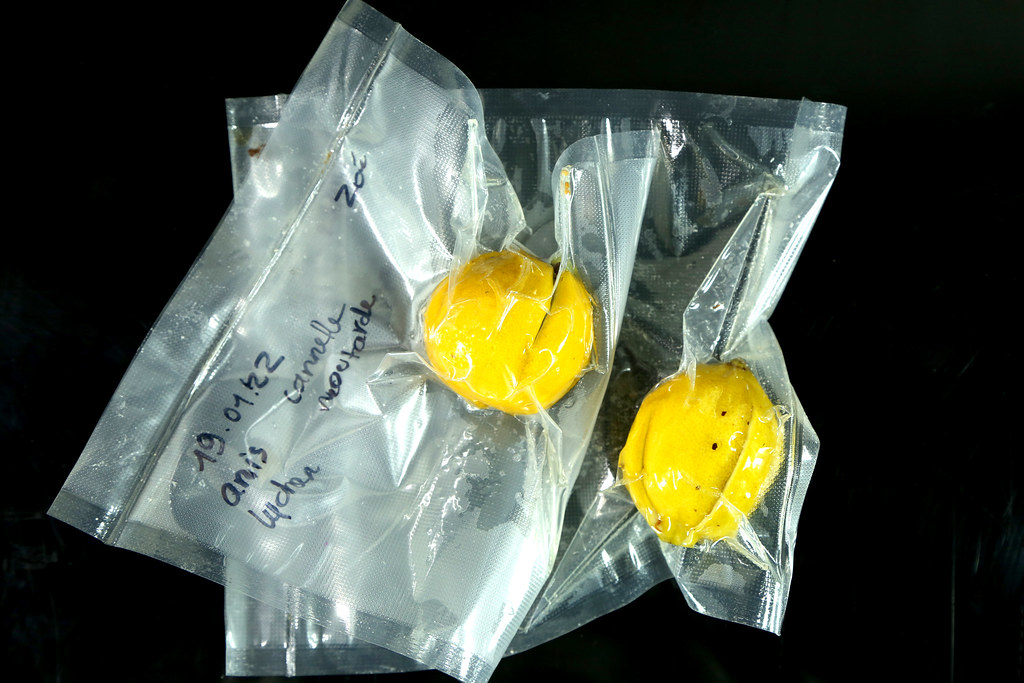

Vivien Roussel led the cultivation of 24 batches with different recipes into a DIY built fermentation chamber Lucile Haute arranged, inspired from Noma (5). Whether one wants to make Kombucha as a fermented beverage for drinking at home or make it for biomaterial production, the process starts the same way, by using tea and sugars to inoculate the fermentation. By playing with the ingredients of the tea, one can affect the colors of the cellulose, from brown or black tea, or red because of hibiskus, or white cellulose made with green tea, or yellow made with kurkuma. However, when the aim is to grow cellulose, the scoby’s environment can be acidified in an untasty proportion and is not suitable for drinking purpose not more.

The Art of Fermentation

As a counterpoint to the design and material approach and reconnecting to the food domain, a fermenting food and beverage workshop was given by the artist Maya Minder for hands-on practice, playfully introducing ancient knowledge on food conservation methods used during the pre-industrial times. The workshop aimed to foster ecological awareness and sensitivity for microbes surrounding us, based on the fermentation teachings of Sandor Katz (6), Noma or Marie-Claire Frédéric (7). Learning about fermentation provides an introduction into the practice and biological wisdom of symbiotic coexistence between humans and the invisible world of microbes, and the healthy benefit it has on the microbiome in our guts.

Industry on Food and Biomaterials and circular economy thinking

The presentation by Pascal Dhulster, a professor in industrial bioprocessing in alimentary systems, described theories of applied practice of food and biomaterial production. Comparing big scale industry with small scale artisanal production, one became aware about the complexity within regulation, protocols and analyzing tools for standardization. What can be regarded as useful and sustainable pioneering in small-scale production can often become a problem if scaled up in volume for industrial production.

The presentation by Alexia Venot introduced the workshop participants to examples of circular economy and circular design projects. A constantly growing population with increasing carbon footprint and waste production are pushing the Earth beyond its regenerative capacity. Within the circular economy, every step of processing in industry, starting from the resources, to production, distribution, consumption, and to the final disposal, is regarded as a factor to be calculated.

Circular economy is a key rethinking of the economy as it emphasizes the balancing of scarce resources with human consumption and disposal. In this rethinking, ecology is in balance inspired by processes occuring in nature – this is termed as blue economy or biomimicry. Circular economy enables processual thinking and valorization of by-products and waste. Projects such as Totomoxtle by Fernando Laposse reintroduced old varieties of colorful biodiverse corn into a small mexican community to build up new small business opportunities for local farmers while synergistically valorizing traditional farming systems. The corn is eaten and also serves for seed production while the husks add value by being used to create marquetry for walls and surface structures. This way the entire production stays inside the community drawing a lot of attention feeding back self-esteem to the community. As a circular project, it empowers local communities, is based on ecosystem friendly production, fair trade and preservation of indigenious knowledge.

Another example discussed was by Colombian Designer Simón Ballen Bottero with his design project called Suelo Orfebre. Having been granted access to gold mines, Simón visited Marmato and soon built trust with the people of Marmato in Colombia. He explored the complex relationship between the local community and the local mining practices. In Marmato, Bottero discovered Jagua, a by-product from the mining industry. Jagua is the crushed ore left behind after the gold is processed and extracted. This sand-like material contains traces of gold and other elements such as silver, iron and sulfur. Today, Jagua has no value, however, in the past it was used by the local glass industry to produce amber and green coloured beer bottles. Bottero started experimenting with Jagua with the help of different craftsmen and glass experts around the Netherlands, Belgium and Finland. To reduce the environmental impact of mining, Suelo Orfebre aims to rediscover the use of this currently valueless material. Bottero realised the importance of leaving visible traces of the mineral in the glass as an alternative to the industrial homogeneity in glass-colouring, and also the importance of applying and sharing this knowledge by the community.

Closer to textile design and fashion, another input came from the fashion designer Corinna Mattner who introduced us to the NGO Fashion Revolution existing since 2013. Fashion Revolution has been globally active through its branches of local activists to bring attention to the fact that fast fashion is one of the most toxic industries in the world. Fashion Revolution was born after the incident of Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh where more than a thousand sweatshop workers died. Fashion Revolution is currently working on a white paper model that fosters activism by creating fashion revolution country offices, teams, and coordinators who independently establish unions, conduct political discussion, and organize sustainable fashion weeks in more than eighty countries so far. It reunites all the actors around the fashion sector, showing that a change in consumption and production is possible. Fast fashion is producing two million items of clothing per year that are never worn, that is, one out of every five pieces that go directly into our landfills. In the last 20 years, the production of clothes has doubled in its total amount and this problem continues to get worse. Those project examples were an invitation for the application of local and circular economy principles in this sector.

There is no waste within Nature itself

In the workshop, the students got a chance to meet with Mial Watkins from Vivant Kombucha, a Paris-based micro-brewery he co-founded in 2018. Watkins’ talk was mainly about the challenges of producing probiotic beverages and the compromise needed to maintain the beverage quality at a larger scale than family. Watkins provided 15 Kgs of Scoby to the workshop that is usually leftover from the brewing process and is thrown away. Instead of being thrown as waste, this material was used for starting batches and for material experimentation with bacterial cellulose, looping it into a circle of reuse as biomaterial for further tinkering and prototypes.

Within the many topics presented, the students were challenged to freely interpret and create projects of prototype enterprise, experiment with materials and spin off ideas. The richness of students’ ideas was evident in the variety of products that were created including kombucha drums, degenerative plasters for biomedicine, beauty products using the benefits of probiotics, cloth made from vegan leather, crochet and knitting samples using kombucha yarn, and graphical manuals and adoptions kits for redistributing scoby for DIY homebrewing.

Notes

1. Workshop “Biomatériaux, Fermentation, Kombucha”

2. Umami, the fifth basic taste, is the inimitable taste of Asian foods. Several traditional and locally prepared foods and condiments of Asia are rich in umami. In this part of world, umami is found in fermented animal-based products such as fermented and dried seafood, and plant-based products from beans and grains, dry and fresh mushrooms, and tea. Hajeb P, Jinap S. Umami taste components and their sources in Asian foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55(6):778-91. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.678422. PMID: 24915349. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24915349/

3. Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(8):e1002533. Published 2016 Aug 19. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4991899/

4. May A, Narayanan S, Alcock J, Varsani A, Maley C, Aktipis A. Kombucha: a novel model system for cooperation and conflict in a complex multi-species microbial ecosystem. PeerJ. 2019 Sep 3;7:e7565. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7565. PMID: 31534844; PMCID: PMC6730531. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31534844/

5. Sandor Katz, The Art of Fermentation: An In-depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from Around the World, Chelsea Green Publishing Co, 2013.

6. David Zibler/René Redzepi, The Noma Guide to Fermentation: Including Koji, Kombuchas, Shoyus, Misos, Vinegars, Garums, Lacto-ferments, and Black Fruits and Vegetable. Artisan Division of Workman Publishing, 2018.

7. Marie-Claire Frédéric, Ni cru, ni cuit: Histoire et civilisation de l’aliment fermenté, Alma éditeur, 2014.

Some of the creations of the workshop will become a part of an exhibition dedicated to plant material at the Museum für Gestaltung at the Zurich University of Arts as part of the ephemeral exhibition Plant-Fever on February 25th.

As for projects upcoming the artist Maya Minder will exhibit together with thr34d5.org at the Artspace Edition Ultra in Brest in March-April together with the thr34d5 NGO and Alexia Venot for collaboration.

The research developed during the workshop will be echoed in Lucile Haute’s exhibition at the contemporary art space Les Limbes as part of the programming of the Design Biennale of St. Etienne from May 14th to June 4th.