Stefan Shankland documents the inexorable mutation of the world

Published 29 March 2021 by Elsa Ferreira

Since 2012, from the heart of the waste processing plant in Ivry-sur-Seine, Stefan Shankland has been studying transformations on a wide spectrum of scales, from molecules to materials to metropolises.

In his Musée du Monde en Mutation (museum of the mutating world), a virtual collection of his experiments, he documents these perpetual and inexorable mutations, “this awareness that we do not live in a world that is fixed, stable, immutable, but inside a world of processes”. Interview.

Makery: What was your first impression when you entered the bowels of this processing plant?

Stefan Shankland: The sheer scale of everything. The orders of magnitude here are monumental, gargantuan, in terms of both spaces and quantities. More than 700,000 tons of waste are processed each year, 100 tons are incinerated each day. This waste is ours—mine accumulated with 1.5 million other residents’ waste. It makes you acutely aware of how much garbage we produce collectively without realizing it. Through this visual, physical, spatial experience, we enter the imagination and the representation of what we produce as a society, or even as humanity.

In your video pieces, the workers are barely represented, or else they are played by dancers who seem to be imitating machines. Are the workers invisible in this world of scrap metal?

This is another aspect that struck me during my first visits. You enter an enormous site that processes waste from 1.5 million residents, but you don’t see anyone. You might see three people working in an office, and there’s a series of trucks that come in, but nobody gets out of them. They dump the waste in the pit, and then they leave. You don’t run into any humans, it’s something very mechanical.

Occasionally you do meet workers, mostly men. But they have a difficult relationship with their professional image. When it comes to the popular image of their profession, there is a kind of shame associated with garbage. The workers don’t voluntarily expose themselves as working in a waste processing plant. We always respected their right to privacy.

“Brûleurs” (burners), by Emmanuelle Huynh and her students at ENSBA school of fine arts, 2020:

Machines are a fundamental issue. Besides being an acronym for the name of the museum, the three “M”s stand for “matter, machines and metropolises”. Have you seen them change since you’ve been on site?

The MMM project coincides with the time it takes to build a new plant that will replace the existing one. It’s a generational leap. We go from a factory designed in the early 1960s and completed in the late 1960s to a plant designed in the 2010s and completed in the 2020s. Not only is it not the same generation of processing plant, but we are no longer living in the same city. That’s what is most striking.

The plant is located within an integrated development zone (ZAC). How are you documenting the mutation of the city?

In the late 1960s, this processing plant was built within an industrial zone where many other factories were already active. Today, it’s the last standing factory to emit a plume of smoke. All around it are offices, residential buildings, new infrastructures made to transport the residents. It’s not at all the same city.

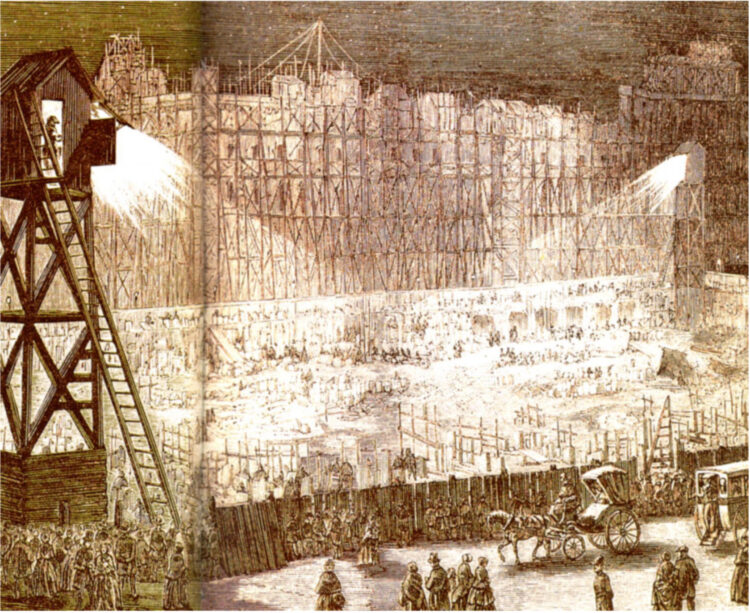

It’s almost archaeological work. We found old archival albums full of photographs of the old factories from before the 1950s. We see construction sites where there are still horses, where the scaffolding is made of wood pieces tied with string, where the holes are made with a pickaxe or with the ancestors of mechanical diggers that look like dinosaurs. You can see time pass through the hundred-year history of building these successive factories. In one century, the world was literally and radically transformed.

You talk about how during the period that Paris was being built according to the plans of Georges Haussmann, the construction sites were open to the public, and even elegant women could be seen walking among the rubble. Today this is still possible (as with the Tunnel de la Croix-Rousse in Lyon) but marginal. More often, the construction work is blocked off and invisible to the public. How does this different approach influence the finished product?

This raises the big issue of the status of construction sites in our inhabited cities. A construction site is a nuisance. Fundamentally, we can’t escape it: demolition, dust, moving trucks, noise, detours… It disrupts the usual flows of a city. Psychologically, it’s a bit worrisome, because we know what we have now but we don’t know what we will have later. There is always an issue around the acceptance of a construction site in an inhabited and restricted space.

When we’ve experienced a construction site from the inside, we have a completely different perspective. We understand the world we’re living in. We rediscover what we don’t see in the city: mud, rubble, destruction, holes, excavation, geological strata, work, fire, water… all these fundamental elements that are usually found in nature. We see what work can produce, we measure ourselves against this physical world. It’s a very sculptural relationship with the world.

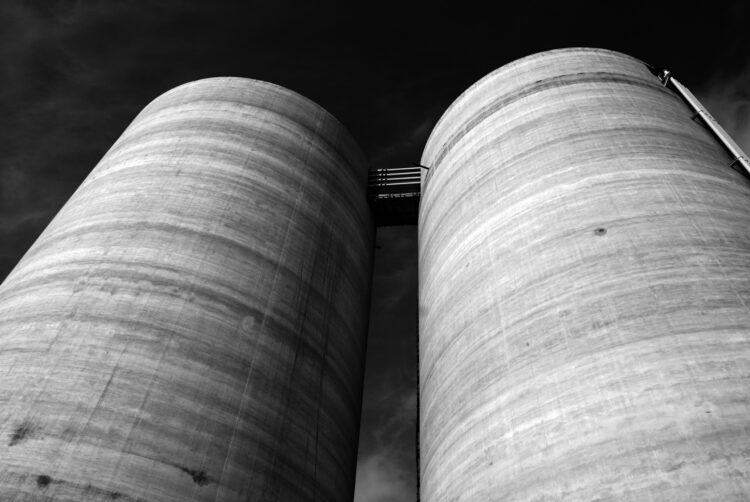

You compare the strata on the silos to geological strata on a cliffside, industrial vs. natural. Is it the same logic with passing time?

From the moment we examine these basic processes of mutation, there is no difference between what is made by humans and what is made by nature: stratification, how time piles up and compresses, phenomena of falling bodies, gravity… The smoke plume, for example, is much fluffier and easier to see when it’s cold outside. It’s a product of both industry and meteorology. I like to recognize in the industrial world these manifestations that I previously associated with nature.

Is nothing fixed in this mutating world?

Considered on a large scale, everything is absolutely and constantly mutating. We know this intellectually, that as the planet evolves over several billions of years, what we’re doing is likely to contribute pretty rapidly and spectacularly to transforming the Earth’s climate.

You imagine a ministry of the mutating world. What would be its role?

Some people talk about a ministry of ecology that would chaperone all the other ministries. That would also be a meta-ministry. It would help us to gain some perspective, to understand that our mutating world is the foundation for any vision, any policy, any projection. It’s what is cruelly lacking today, even more so in the current health crisis. We are incapable of projecting ourselves into the day after tomorrow, one month, six months into the future. We would need a ministry with this capacity to make plans within a continuum.

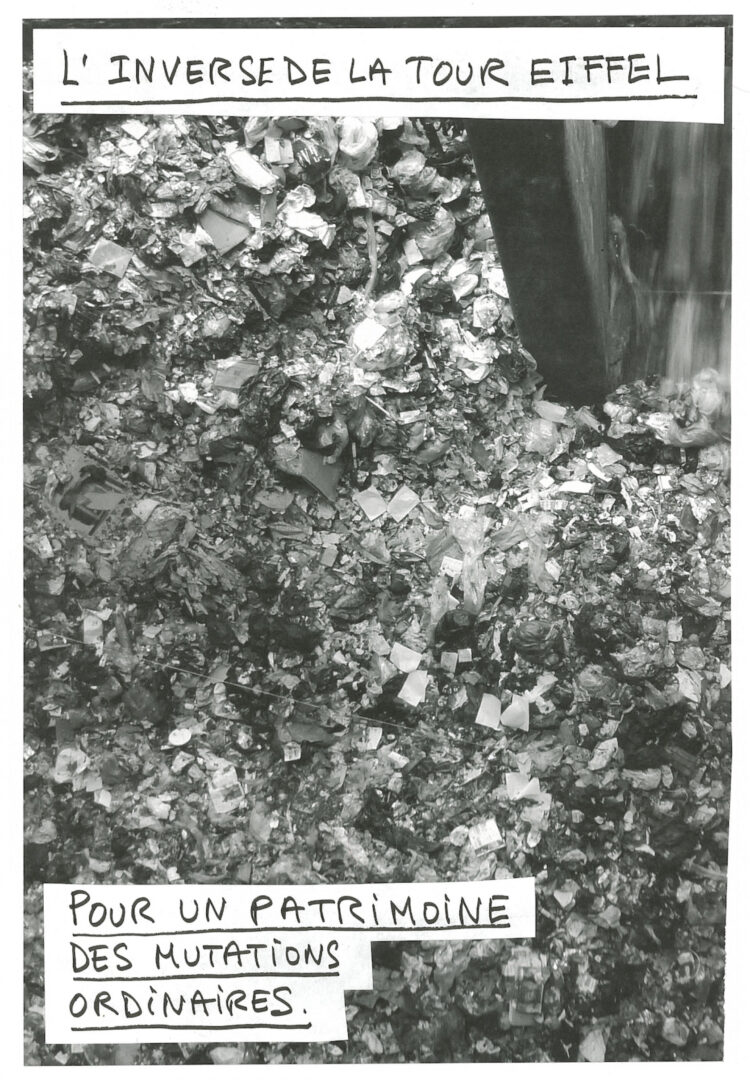

I’m currently working with the filmmaker Ann Guillaume on what we called a Manifesto on the patrimony of mutations. Perhaps we need to apprehend our mutations as objects that have a patrimonial value, to build a culture of mutation? Not so much to place them in a museum, but to recognize their human and cultural value. For example, instead of designating the Eiffel Tower as patrimony, let’s consider as patrimony the fact that it was designed, built, disassembled and recycled.

We’re terrified of mutation, because we see it as invasive or dangerous. But we can’t resist it, we need to appropriate it and develop in a positive and interesting way within this paradigm.

We are at a key crossroads in our collective existence, at a moment, perhaps, of mutation. How do you react to the expressions of “the world before/the world after”?

I’ve been working with situations of mutation for almost two decades. The world before and after is everywhere, all the time. Inside an artist’s studio, what you did yesterday is past. We need to make decisions today that commit us to tomorrow. When you find yourself at the heart of the reality of the world—i.e. a mutating entity, as we all are, and as are in particular creative activities—we face this disruption every day.

Visit the Musée du Monde en Mutation