Post Growth: The Biosphere’s Work and The Solar Salary (2/2)

Published 23 March 2021 by Maxence Grugier

Post Growth is a series of initiatives by the collective DISNOVATION.ORG that puts into critical perspective the imbrications between growth mechanisms and contemporary ecosystemic crises. Part 2 of our interview.

Founded in 2012 by Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska, DISNOVATION.ORG is both an art collective and an international workgroup engaged in the crossovers between contemporary arts, research and hacking. Artist and philosopher Baruch Gottlieb joined the collective in 2018. Together, they develop situations of interference, debate and speculation that question dominant techno-positivist ideologies in order to foster post-growth narratives. Their research is expressed through installations, performances, websites and events. They recently co-published A Bestiary of the Anthropocene, an atlas of anthropic hybrid creatures, and The Pirate Book, an anthology about pirated cultural content.

Post Growth was initiated by DISNOVATION.ORG in 2018, with Clémence Seurat, researcher and publisher of eco-political issues; Pauline Briand, journalist specialized in biodiversity issues; Julien Maudet, designer of critical and political games. Read Part 1 of our interview.

You suggest that the ubiquitous language of political economics is quite deficient in describing our relationships with the living world and the biosphere. What kind of language needs to be reinvented?

To quote George Box: “All models are wrong but some are useful.” We are used to understanding and evaluating our daily interactions in society, in the world and in the biosphere through economic metaphors. But contemporary standard economics is still based on the assumption that natural resources are unlimited, where their value tends toward zero.

This distorting prism through which we explain the world occludes the work of the biosphere and how materially dependent our societies are to ecosystems.This premise led us to research how to describe and apprehend our relationships with the living world, especially the energy and materials circulating in the biosphere, to hyper-visualize these physical dependencies instead of obscuring them.

The Farm (video), DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb, 2021:

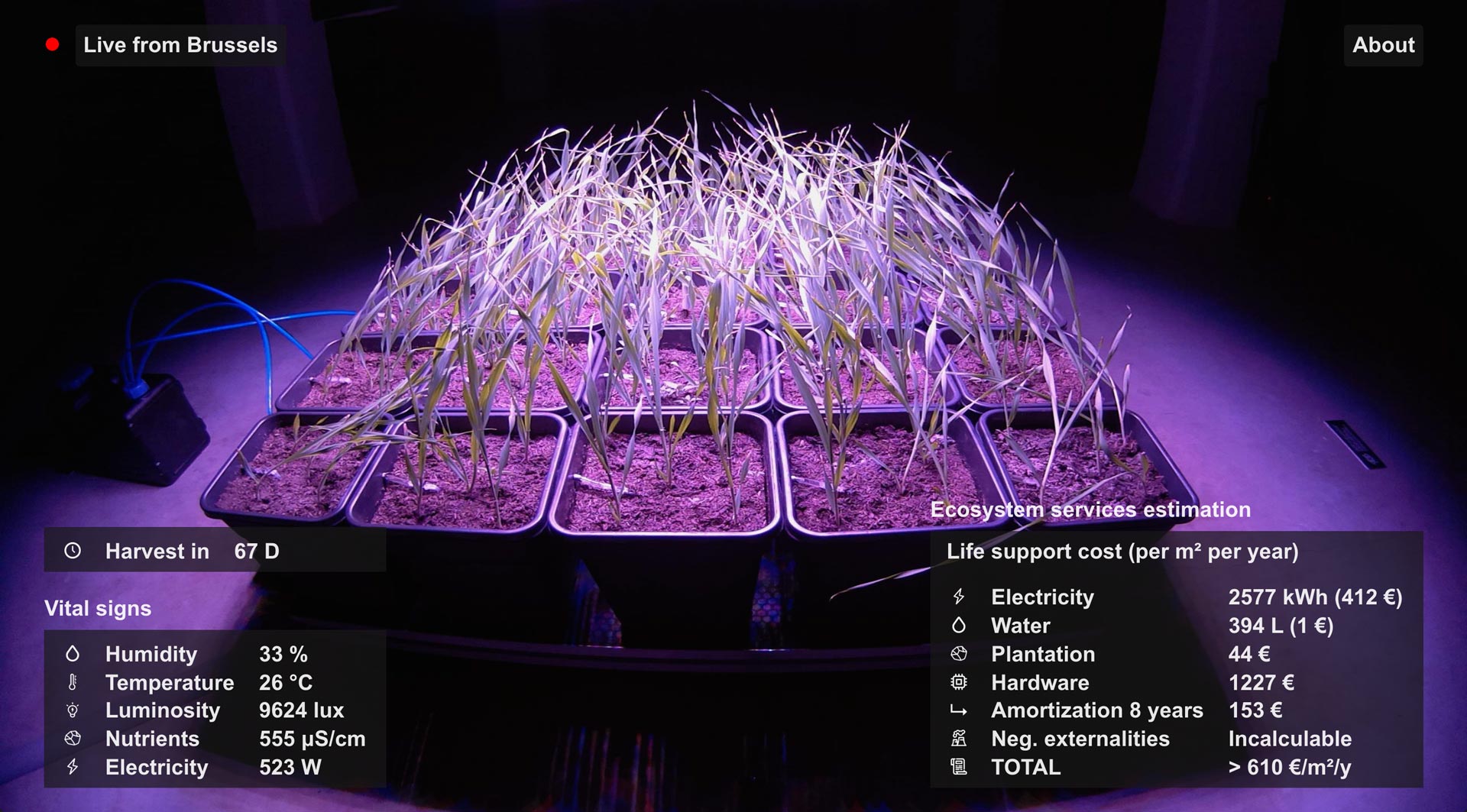

In The Farm, an artistic experiment in cultivating 1 square meter of wheat above ground, you call attention to the magnanimous work of the biosphere, otherwise known as “ecosystem services”. How did you proceed?

The Farm experiment consists of artificially cultivating 1 square meter of wheat within a closed environment, where the main conditions for survival (water, light, nutrients, etc.) are provided, measured and monitored by an automatic system.

This model allows us to estimate the orders of magnitude of material and energy flows that are otherwise provided by ecosystems on arable lands. From this we can extrapolate to the huge scale of ecosystems’ contributions essential to all human and non-human processes, conventionally obscured in standard economics.

Based on this experiment, we estimate that under ideal conditions it is possible for one square meter to produce 3kg of wheat for 610€ per year. This experimental cost of over 200€ a kilo is astronomical when compared to the 0.15€ per kilo price at which wheat is exchanged on the global market. Here we can begin to understand the magnitude of all the ecosystems’ contributions which are excluded in the dominant model, or underestimated when “nature” is abusively counted as capital.

What is your opinion of the growing potential of agriculture in closed spaces? I’m thinking of vertical farming, or urban farming in shipping containers launched by the entrepreneur Kimbal Musk.

The Farm aims to make more tangible the fundamental challenge behind part of the agro-industrial sector’s promises to meet the nutritional needs of urban populations through indoor farms and other artificially controlled environments. This fantasy is presented ever more frequently as an appropriate response to climate breakdown.

This 1-square-meter experiment highlights the vast technical infrastructures and energy flows required to grow a staple food such as wheat in an artificial environment. In the current economy, though it can be profitable to produce water-intensive agricultural produce such as green vegetables and tomatoes in a closed environment. this is clearly not the case for products with higher caloric values such as starches, which supply an essential portion of energy for human life.

Furthermore, from a systemic perspective, the profitability of this industrial production depends on the availability of cheap fossil fuels, not to mention the extraction of resources and global pollution, including all the subordinate processes, from mining to manufacturing electronic devices and international shipping, which are also largely under-estimated. This experimental farm aims to reveal these numerous layers of interdependence that are inadequately accounted for in prevailing economic models. It also provides a speculative estimate of the ecosystemic services that a closed environment must reproduce at high social, energy and ecosystemic costs.

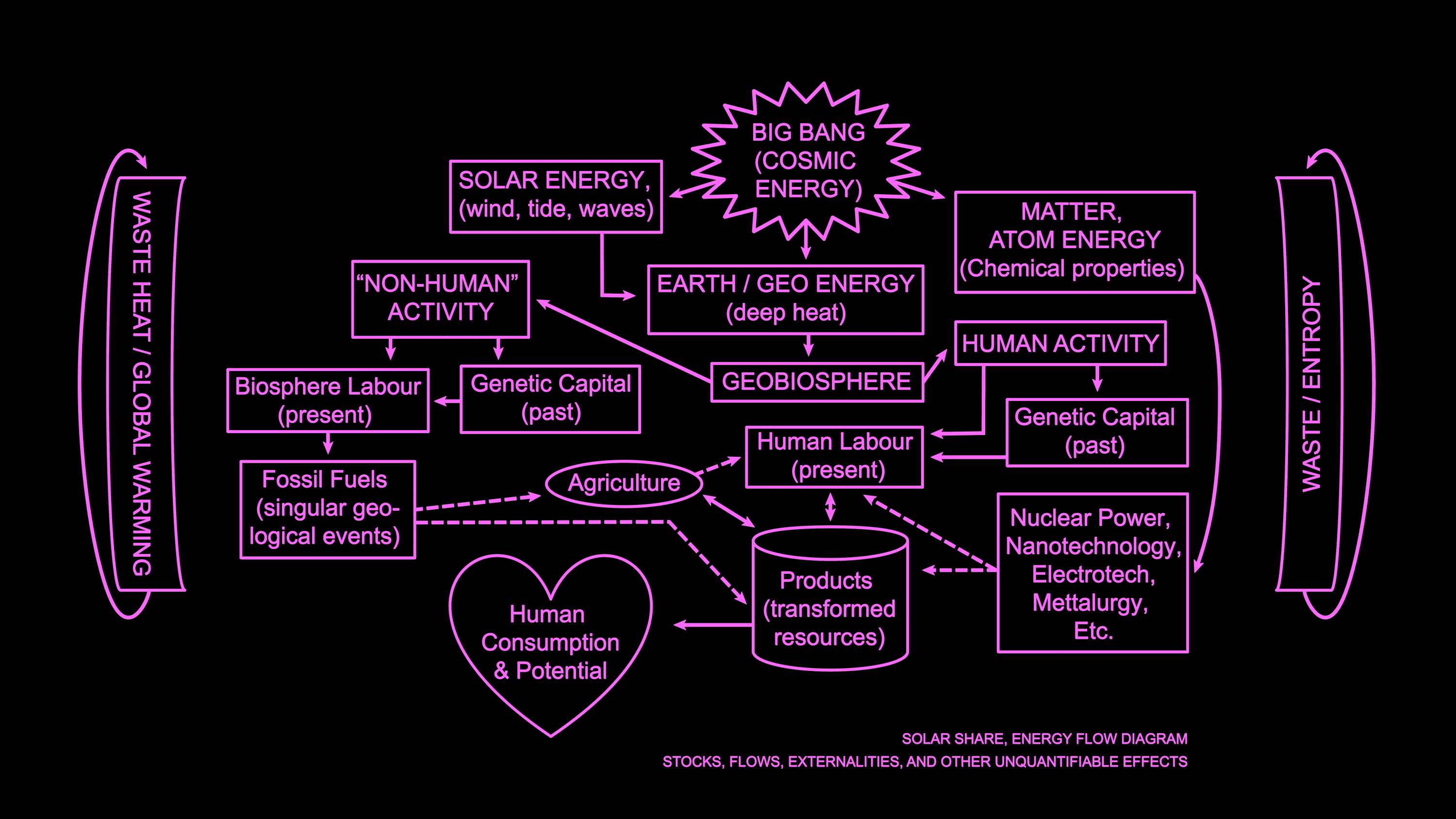

In Solar Share, you sketch out an economic model based on solar radiation captured by the biosphere. You even talk about “Solar Salary”. What led to this unorthodox way of thinking?

As previously mentioned, the dominant models used to explain our material and energy economy remain unsatisfactory. The concept of value habitually represented in current economic models through prices is an ideological convention.

In Solar Share, we make manifest economic contributions, anchored in the physical processes that have sustained life on Earth over very long timescales. Through analogies such as “Solar Salary”, we explore the conceptual and artistic potential of an economic model based on solar radiance, solar income.

Over the past few decades, the concept of sustainable development has been promoted to serve capitalism’s intrinsic need for expansion and growth, ironically expressed through increasingly short-term modes of financing.

How can we, on the contrary, imagine a radically different approach to “sustainability” grounded in the material processes on which we depend for our “sustainability”?

In order to project sustainability over the very long term, we propose to observe what has sustained life on Earth to this day. We sought out basic principles such as solar radiation, and generated economic premises based on these. We want to study what this shifted point of reference re-articulates, questions and highlights, so that we can propose new modes of scientifically understanding, valorizing and describing the world. Concurrently we can elucidate the limits of what is relevant or even possible to quantify.

The Solar Share model offers various conceptual tools informed by contemporary scientific research to practically comprehend the transformation and circulation of energy in our societies. To this end, we generated a series of speculative and radical economic models based on the primary energy source that is truly renewable within the biosphere on very long timescales: energy emitted by the Sun.

If we consider the solar energy inputs captured by the biosphere as an insightful magnitude to imagine a “viable planetarity” (Benjamin H. Bratton), what tangible or conceptual forms could this new economic model take?

Certain energy flows in the biosphere are truly renewable, and a large part of these renewable flows are indirectly activated by solar radiation (winds, precipitation, etc). To get an idea of the scale of these energy flows, certain accounting methods can help grasp and compare the orders of magnitude involved.

This is what stimulated us as artists in the Emergy environmental accounting model. This controversial model proposes an in-depth accounting of energy stocks and flows, processes that can be extremely slow and vast, as are the various energy contributions essential to life on Earth.

At the heart of the Emergy methodology is sunlight, which is responsible for most of the energy sources on which we currently depend, especially wind, tides, and above all, fossil fuels, which are ancient sunlight. The Emergy model produces an estimate of what portion of the energy flows of a geographical area is renewable. This quantity is expressed in “solar equivalent Joules”. This method does not pretend to provide absolute measurements, but it allows us to draw useful scalar relationships.

Of course, some regions of the world receive more sunlight than others, while some regions “use” more than others. In Europe, we use much more energy than we can directly get from the sun or the wind.. Most of the energy we use is imported or extracted in concentrated fossil forms—mainly oil, coal and natural gas.

For example, Brussels is one of the least sunny capital cities in Europe, receiving on average only 3 kWh/m2 per day and 1000 kWh/m2 per year. But its energy consumption is comparable to that of most European cities.

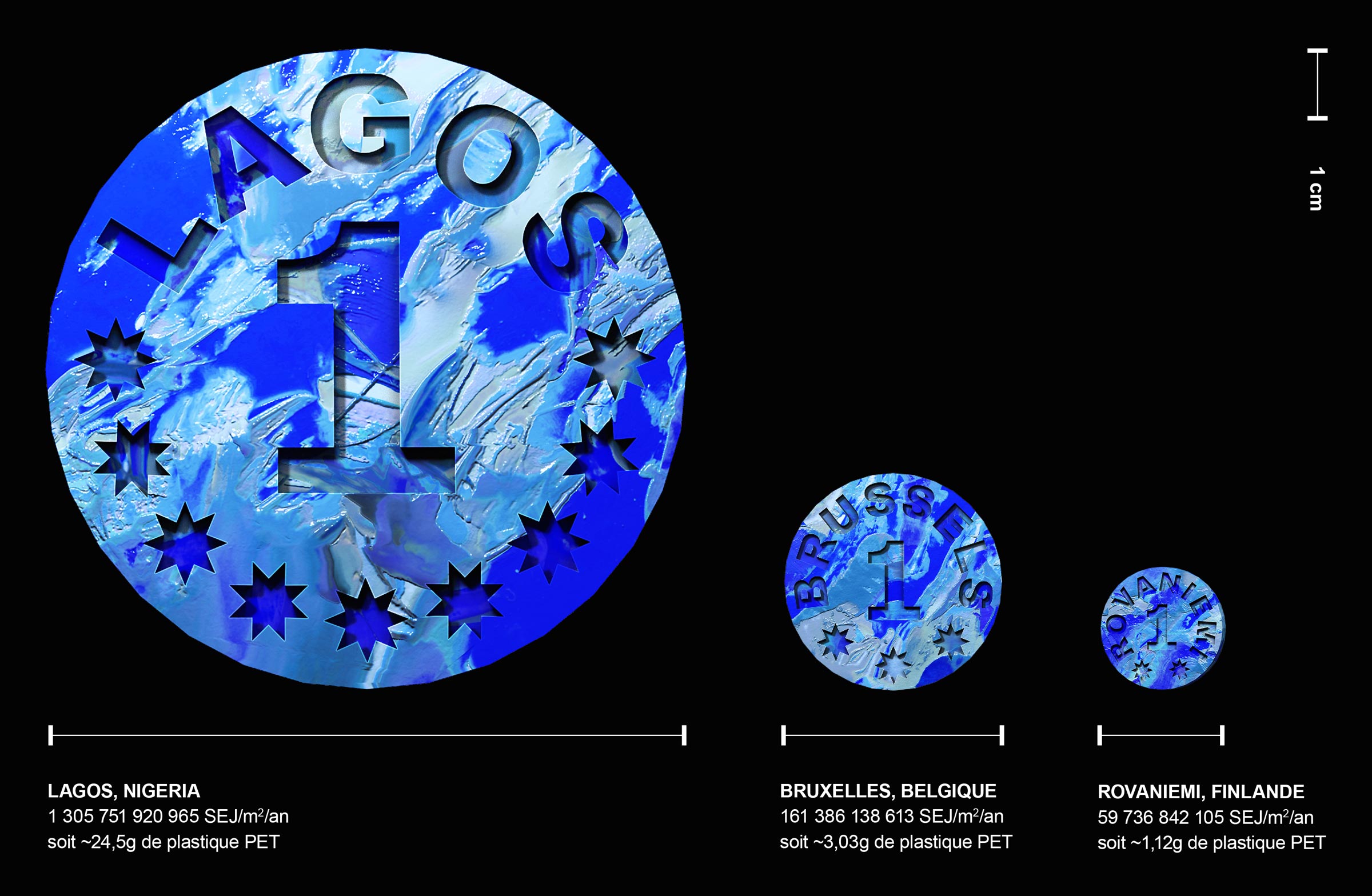

The Solar Share coins allow us to physically manifest the renewable processes activated by the sun on a specific area. They allow us to compare the prevailing models of economics with this very tangible, present and situated order of magnitude of primordial processes of the biosphere, which underlie all economic activity.

These coins are made of recycled PET plastic. Plastic is a by-product of oil, ancient sunlight concentrated into organic matter over millions of years. We converted the average quantity of renewable energy flows within a given geographical area (for example, per square meter per year) into their Emergy equivalent in plastic.

How might our understanding of economics be transformed if the monetary instruments that we use had a value equivalent to the solar energy required to reproduce them locally? As a speculative response, we have proposed the Solar Share coin as a physical equivalent to the average amount of renewed energy per 1 square meter of the specified geographic area, according to the Emergy model (incorporated energy).

This is illustrated above with a plastic coin weighing 1.12g, which corresponds to 1m2 in the area of Rovaniemi (Finland), a 3.03g coin corresponding to 1m2 in Brussels (Belgium), and a 24.50g corresponding to 1m2 in Lagos (Nigeria). In order to localize the concept even further, we make a new coin for each place where this project is presented.

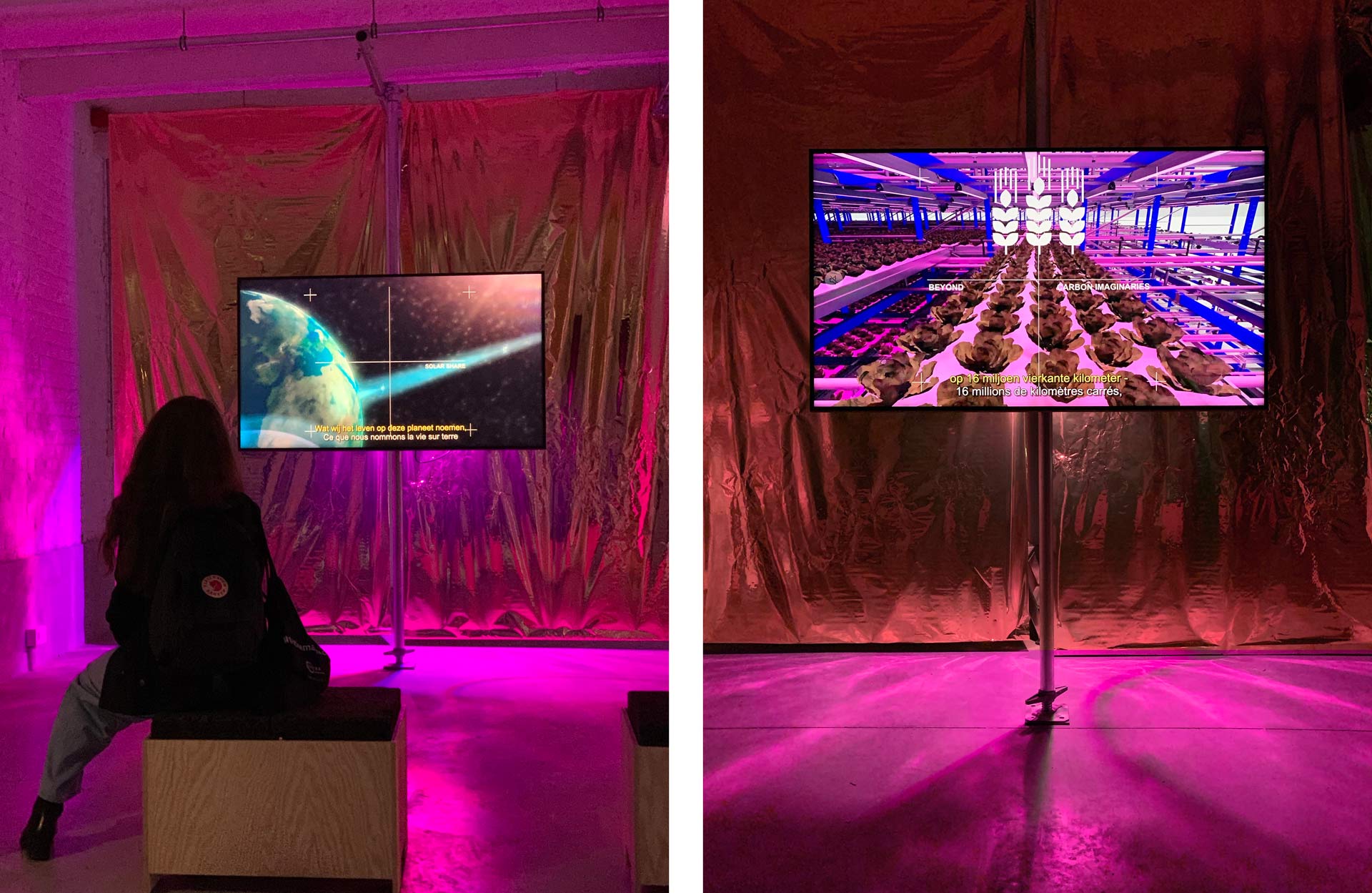

Solar Share (video), IMAL Brussels, DISNOVATION.ORG & Baruch Gottlieb, 2020:

What are the next phases in this research series in the months and years to come?

These various projects will be exhibited in summer 2021 at Impakt art center in Utrecht and during the STRP festival in Eindhoven. In terms of research, in the following years we will be working with labs and universities, including Paris 8, UC Berkeley, UC Louvain La Neuve, TU Dublin…

We have designed these works as prototypes that are progressively integrated into a toolkit and web platform, which can be exhibited and used by other activists, researchers, teachers and media. They are provocations, ways to stimulate changes in perspective, but also proxies for tackling difficult and relatively inaccessible topics in ways that are trans-social and trans-disciplinary.

Read Part 1 of our interview

More information on the Post Growth research series

Join the conversation on Discord