Thomas Ermacora: “I hope for a hundred or so fabcity districts in 2030”

Published 10 July 2018 by Elsa Ferreira

Early supporter of the fabcity, the urbanist Thomas Ermacora is one of the speakers of the Fab City Summit. He explains why the future of cities is in the hands of a new generation of techno-creative people.

London, from our correspondent

Technologist, futurist, urbanist, maker, architect…Thomas Ermacora is familiar with extended titles like presentations and other TED Conferences. It should be said that the author of Recoded City: Co-Creating Urban Future, published in 2015, is dedicating his career to rethink the city to make it more collaborative, participative, digital, and most importantly, intelligent.

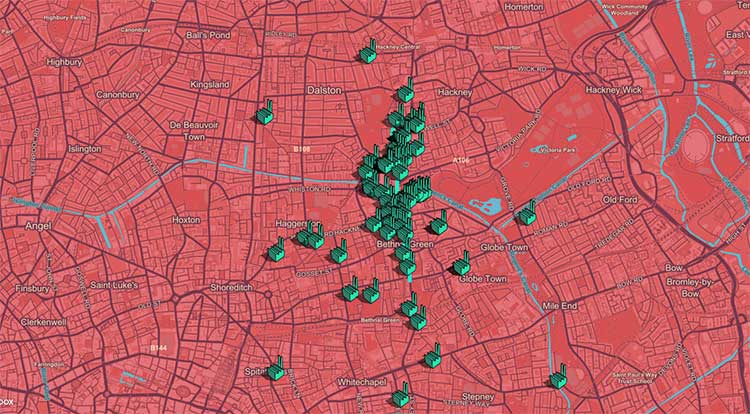

The Italian-Danish, 41, based in London, is putting his theory to the crash test of reality with four projects, all of which are proofs of concept (POC) of his vision: Clear Village, organization through which he creates spaces to give a common goal to communities, the innovation and cultural center LimeWharf, the makerspace Machines Room and lastly Maker Mile, a mini-district of London where studios, workshops, and digital and creative new industries are gathered. Interview.

One of the main objectives of the fabcity is to relocate industry at the heart of the city. Why is it important?

There are two main reasons. The first one is that we have designed a supply chain in an extremely unhealthy way for the planet. Not just because of pollution, environmental and climate change but also because it’s hurting people. Supply chains are terribly unfair and only a few people make money off the back of the planet and people.

One of the opportunities of the maker movement, in association with cities, is to bring industries closer to inhabitants’ needs, to be able to produce customized goods with local materials.

The second reason is that there is a tremendous opportunity gap that needs to be addressed by cities in terms of capturing talent. Talent is the most expensive currency to any organization, city, government, nation. It is the hardest thing to form and the hardest thing to keep. One of the beautiful things with makers is that it’s a very self-learning and adaptive intelligentsia. It’s a new class of people.

There are however drawbacks to produce in the city: noise, pollution, cost of premises…What to do?

The approach we have of industry is mass production and then shipping. With digital fabrication, we can decide how much we need, how much volume, and we can use local resources and therefore have a smaller, less polluting production facilities. We can recycle certain materials and create a circular relationship. We need to change the way we sell products, we make products, and we upcycle products.

This is not about going back to the first industrial revolution. Yes, there is a little waste, yes they are some shortfalls: we are still using quite a lot of electricity, especially when we go for mass production. We are however witnessing the development of renewable energy such as solar energy. If we ally making and supplying and we circularize, then, within the the next two decades, we can radically transform the environmental performance and well-being in the city, while bringing back some of the jobs that have been outsourced to developing nations.

It’s a complex equation that we will not resolve overnight, but we are embarking on a new conversation.

According to you, makerspaces are the secret for a truly smart city. Why?

I was an advisor for the world economic forum in an initiative called the future of urban services and developing initiatives. Mayors, political and technological experts talked about how they thought they could influence the city of the future. One of the main points of our discussions revolved around public-private partnerships, true development drivers.

Makerspaces could be the secret to making smart cities smart https://t.co/v8jTCDgnIq pic.twitter.com/zxhj0bDySe

— World Economic Forum (@Davos) March 22, 2018

The clustering effect of fablabs and makerspaces, this work and fabrication ecology, could constitute a new kind of public-private partnership that could help local governments, local actors and makers to work together in order to reimagine public services. The nimbleness of the fablab community would be very helpful for cities.

Supporters of the fabcity give Precious Plastic as an example. Beyond the symbol, is it a real solution to plastic recycling?

I don’t believe Precious Plastic is set to expand. I think it’s an iconic project which shows that citizens can organize themselves to do something together, but most cities want a solution that requires less volunteers.

We want to use the example of Precious Plastic to redefine the way we recycle plastic in cities. People hate plastic but I think it’s the wrong approach. We need to love plastic. Plastic is an amazing resource. Except that we are abusing it, throwing it in the oceans and it ends up in our bodies. We need to treat it as a precious material.

In London, the Maker Mile district brings together companies with similar activities, like Technology Will Save Us and Sam Labs. What are their relations?

Mc Donald and Burger King often buy their premises close to each other because they know they will need to spend a lot of energy finding the people who want to eat that kind of food. In the same way, the magic of the MIT Media Lab comes from the fact that people with competing skills share the same environment. Nature itself is organized in that same manner: trees all compete for light, however they create an ecosystem together.

A maker company needs to find workers with specific knowledge and be able to learn from people around it. We need to build places where people better themselves by learning from each other through emulation and mixing with each other.

When they arrived, Technology Will Save Us counted seven employees. They now have more then thirty. As for Sam Labs, it tripled in size.

Makerspaces are struggling to find business models. How do you see their future?

I am convinced that the way makerspaces are managed today is absolutely absurd. The only makerspaces that really survive are the ones that are supported by the government, by a grant, or a campus, either corporate or a university. Some are managed by the community, but they are hackerspaces.

We should create hybrid accelerator programs that connect real estate developers with local decision-makers, with government subsidies to attract maker talents. Real estate developers could provide their premises at a lower cost, even for free, which would be an attractive business cluster for qualified jobs in the districts.

I hope the maker community will be able to get together in a such a way that this creative class is integrated and and capable of paying rent once the districts are gentrified.

Actually, how does one avoid gentrification in this process you call creative regeneration?

The problem isn’t bringing more money to a district. It is making the people who make their district interesting flee. Real estate developers must realize that if they gentrify, in a certain way, they are depreciating the human capital. The most successful districts are those that present the most diversification in terms of age, ethnic origin or religion. A rich district in not necessarily a successful district.

One also needs to rethink public spaces. The quality of urban life lies in intermediary places, those that are not private. The city is a large shared living room, like an agora. With the price of real estate, it is very unlikely that, in future, everyone will have a large house. Public spaces are therefore all the more important.

How does one convince real estate dealers of this change in paradigm regarding construction in the city?

Real estate developers must have a return on their investment. They are therefore cautious. But they also know that if they don’t have anything to make their district interesting, they will not sell their apartments. It is time for this to change and I hope that we can do this in a way that also benefits the maker community, not just real estate developers…

I had to close down my makerspace Machines Room: the premises were sold and the rent was going to double. We were already not making any money, and I would have had to lay people off. We decided to move into two containers at Containerville (a hub of work spaces for small businesses and start-ups in East London, editor’s note) rather than into large premises.

You are very optimistic about the fabcity. What do you expect concretely?

My version of hope is inspiration. Maybe, when you were a child, you had, a parent, a teacher, or an aunt who taught you to open your mind and strengthen your ability to think differently. I call this “hope capital”. I think the role of cities is to develop this “hope capital”.

Concretely, I hope that by 2030, we will have a hundred or so fabcity districts in more than sixty cities throughout the world that can collaborate, expand knowledge and possibilities, through digital fabrication tools, to transform supply chains.

It’s a movement that will create enough momentum to create an inflexion point that cannot be reversed.

Thomas Ermacora and Open Source Urbanism, TEDxBeaconStreet, 2017:

Thomas Ermacora was present at the Fab City Summit in Paris, for a round table “Fab City Collective”, on July 13.