Bela, just a few milliseconds away from a Raspberry Pi

Published 6 February 2018 by Elsa Ferreira

Sometimes, it all comes down to a few milliseconds. Case in point: Bela, a nano-computer that processes audio signals and sensors with ultra-low latency. For musical ears, but not only.

London, from our correspondent

To understand Bela, you need to compare it to other systems available on the market. Beginning with the Raspberry Pi, which like Bela, is a nano-computer. The main difference, according to Giulio Moro, one of the developers of this British project, is that the Rasbperry Pi doesn’t have integrated speakers or analog inputs. So you can’t, for example, plug in potentiometers or other basic elements of a DIY musical instrument such as microphones, without using extensions.

Arduino next, which allows you to plug in all sorts of sensors and analog tools. But it also doesn’t have integrated speakers, and you need to hook it up to a computer in order to play an instrument, Giulio points out, which is “expensive, cumbersome and prone to failures”. In the case of a sound installation, it’s not very convenient to leave your computer running in a corner for the duration of the exhibition.

Above all, these two systems are relatively slow. Because of their connectivity—both need to be plugged into extensions to play a musical instrument—and also because, as opposed to Bela, the latency of the audio system was not the priority of their manufacturers.

“You have to look at the worst performances. In general, it’s fine, but when the computer is busy doing something else, there will be glitches in the audio. We made it so that our system always works. The audio is high priority, even at the expense of other functions. It’s what’s called a real-time operating system.”

Latency and constancy

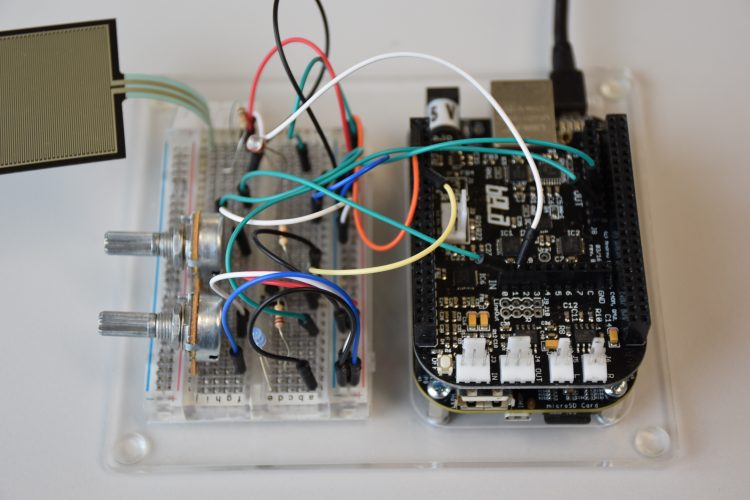

Bela is based on two existing technologies. On the hardware side is BeagleBone Black, an open source integrated computer. Bela attaches itself to this platform, adding its connectors. On the software side is Xenomai, an extension for a real-time operating system on Linux that allows you to set operating priorities for the system—in this case, the audio signal.

This results in a gain not only in the processing speed of the signal (0.1 milliseconds), but also in constancy. This is an important element in the perception of music, says Giulio, even to untrained ears. Student researcher Robert Jack studied the effects of latency on the perception of the quality of the instrument. “While the subjects didn’t necessarily perceive the difference in latency between 0 and 10 milliseconds,” continues the Bela developer, “these variations had a negative effect on the perception of the instrument. The subjects perceived a signal with 10 milliseconds of latency and variations, or ‘jitters’, as being just as bad as a signal with 20 milliseconds of latency.”

Kickstarted in four hours

Development of Bela began in 2014. At the time, students Victor Zappi and Andrew McPherson were working on a musical instrument that could be hacked. “They started off with circuit bending,” says Giulio. “But it’s difficult with a digital instrument, because everything is inside the chip. So they decided to deconstruct the software part, what’s inside the ‘virtual circuit’, and place it on a prototyping board.”

Hence the D-Box, an instrument that is played by hacking, which determines the requirements of the mini-computer that it needs to operate: integrated speakers, lots of signal inputs and outputs, and very high speed. The Bela project was launched.

Demo of the D-Box (2014):

Developed at the Augmented Instruments Laboratory, affiliated with the Center for Digital Music at Queen Mary University of London, Bela has evolved through several iterations. The developing environment came about when one of the ten students who were gravitating around the project needed to visualize the audio signal. So they added the language Pure Data to replace the traditional accessories used for sound effects with digital sounds, while retaining all their expressiveness, Giulio explains. “Bela was never a research or thesis project. It was always a parallel project.”

Until 2016, the students used Bela internally and gave occasional workshops to demonstrate the devices they had conceived using the platform. On February 29, 2016, they launched a Kickstarter campaign to go into production. In just four hours, they achieved their (modest) goal of £5,000 ($5,685). One month later, they broke the counter with a total of £54,000 ($61,425) raised. “We’re pretty well established in the new instruments community,” Giulio explains. “And it’s a new tool.” In October 2016, they launched the company Augmented Instruments Limited and began to sell the product.

Binaural fusion and VR

Since then, the little business is doing well. Augmented Instruments Ltd has sold 1,000-1,500 Belas (at £140 for the starter kit) and is preparing to launch a new product. The team has also received funding: £25,000 ($28,435) from Innovate UK and £9,000 ($10,235) from the university, which will help create activities for children and beginner makers.

The goal is both to make the product more accessible and extend its applications. After music, the e-textiles community is beginning to use integrated nano-computers, spurred on by Rebecca Stewart. This lecturer in the School of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science at Queen Mary uses Bela inside wearables during live performances: “Usually, we place sensors on the bodies of the artists or dancers, and the signal has to be sent to a computer to be converted into an audio signal. Here the speakers are placed directly on the body, so we don’t have to wonder which artists the sound is coming from.”

She is also using Bela’s signature low latency to explore binaural fusion, a process that transmits sounds more realistically by transcribing location data, and a particularly useful application for virtual reality environments. “Bela is powerful enough to use binaural sound, and its ultra-low latency offers very fast response times,” she says. Her dream project is already in progress—collaborating with the immersive theater company ZU-UK to create a virtual soundscape that visitors can wander through.