Krzysztof Nawratek: “Urban re-industrialization is a political project”

Published 16 May 2017 by Ewen Chardronnet

#Fablab Festival. Interview with Krzysztof Nawratek, architect and urbanist from the University of Sheffield, about the essay he directed, “Urban Re-industrialization”.

Toulouse, special report

The Fabcity was at the heart of Fablab Festival 2017, leading up to the Fab City Summit, which will be held in Paris in July 2018. For architect and urbanist Krzysztof Nawratek, who was invited by the festival and the Makery medialab to speak in Toulouse on May 13, no model of the Fabcity is complete without the radical inclusion of every element of urban life—from heavy industry to migrant and temporary workers.

Contrary to the reigning enthusiasm in Toulouse, Nawratek’s perspective is critical. He believes that urban re-industrialization is too often interpreted either as a method to increase commercial efficiency in the context of a politically supported green economy, or as a nostalgic caricature of the creative class mutating toward a vision based on 3D printing, “boutique manufacturing” and craft.

These two visions confine urban re-industrialization to the current neoliberal economy and urban development based on property and land speculation. Nawratek proposes a more radical form of urban re-industrialization. What about a progressive socio-political and economic project designed to create an inclusive and democratic society based on cooperation? Interview.

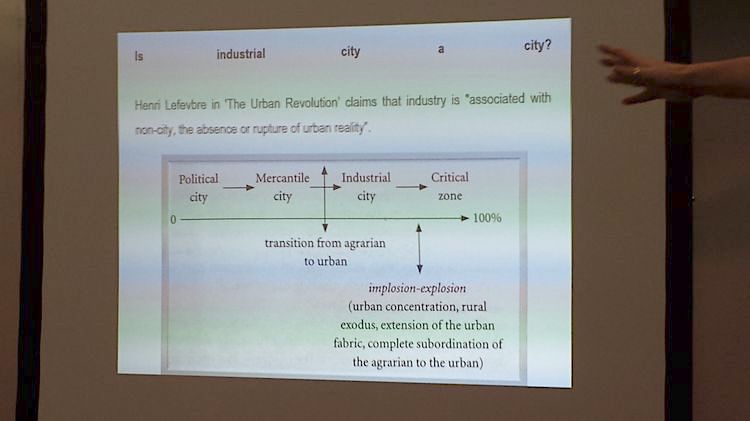

Your book is “an attempt to see a post-socialist and post-industrial city from another perspective, a kind of negative of the modernist industrial city. If, for logistical reasons and because of a concern for the health of residents, modernism tried to separate different functions from each other (mainly industry from residential areas), the Industrial City 2.0 must be based on the ideas of coexistence, proximity and synergy.” Could you explain?

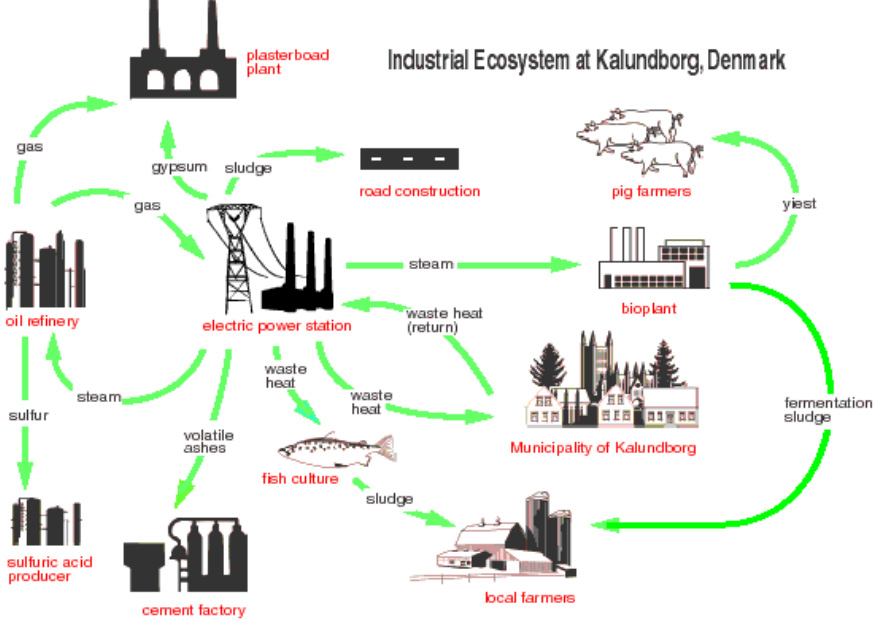

The are two main reasons—one is practical, the other is ethical. Practical is based on an idea of industrial ecology, with a Kalundborg Eco-Industrial Park as probably the best example of how clustering diverse industries could benefit them all. Cities, mainly European and Asian cities, could already be seen as dense socio-economical ecosystems; therefore Industrial City 2.0 just taps into existing connections and makes them stronger, more synergetic. Ethical argument is to some extent similar—making existing linkages stronger, creating new relationships, building synergies that create a more inclusive city. Radical Inclusivity was the title and theme of my previous book. I am extremely interested in the idea of radical inclusivity, I see it as an alternative to Marxists’ idea of class war or a Schmittian idea of conflict as an essence of politics.

You mention the fact that re-industrialization in Western Europe and in the United States only really started a few years ago, when the 2008 economic crisis bankrupted the urban development model based on real estate speculation and liquid capitalism. Barcelona and Paris support relocation through micro-industry, while other neoliberal politics encourage gentrification of city centers by the creative classes, promoting “industry 4.0” and massive robotization. What’s your opinion on this?

Neoliberal politics, as David Harvey rightly said, is a “revenge” of capital after years of the welfare state era. Neoliberal politics were and are about transferring power from a relatively democratic and egalitarian post-welfare society to the capitalist elite. Robotization and creative class gentrification are just new symptoms of the same old neoliberalism. The goal is the same: to create a static, hierarchical society. I am not against hierarchies. I am fascinated by the Barcelona case (especially the Poblenou neighborhood project), where bottom-up and top-down forces meet. I think it is too early to assess this project, but it looks very promising. Industrial City 2.0 is definitely a non-neoliberal project—it is an attempt to create an inclusive, egalitarian but also economically robust city.

FAB12 was held last year in Shenzhen, the capital of micro-industry. Your book talks about globalization, from manufacturing in China to exportation, from transportation’s carbon crisis to protectionist measures adopted in the U.S. and Europe. Since the election of Donald Trump and his program to reject the COP21 agreements, a political discourse of “ecological sovereignty” has emerged, as in some criticisms of the TAFTA and CETA agreements. In this context, how can we introduce a resilient vision of urban re-industralization?

It is an absolutely fascinating question, but I am afraid I do not have a good answer. I am sure ecological issues will become more and more important in Europe, but it is difficult to imagine a “proper” green movement that is not really global. Therefore, I feel slightly dubious about the notion of “ecological sovereignty”. However, it could be re-framed as a simple idea focused on “doing our part”. It could also be an interesting way to connect to urban re-industrialization, as an attempt to (re)build a city as a strong political and economic subject.

There is no mention in your book of the Fabcity model (from PITO to DIDO). What do you think of Data In / Data Out?

You are right, and I think it is a surprising omission. However, I think that the whole book is related to the idea of Fabcity somehow. Concerning Data In / Data Out, it sounds interesting, but the focus on information may be overestimated. A few years ago, I was working on a diaspora strategy for Ireland, and I found it interesting how immigrants work as “live mediators” between diverse localities. I feel that Fabcity is missing the human element. I also feel that spatial thinking is not fully developed in that area. So as a starting point it sounds good; I just feel it is too simplistic.

Why do you borrow Ernst Jünger’s controversial idea of “total mobilization” to defend urban re-industrialization as a new form of universalism?

Ernst Jünger is a pretty controversial persona, but my chapter is an attempt to “reclaim” his work and use it as an essential element of a progressive, “radical inclusivity” project. At the center of his notion of “total mobilization” is the argument that alienation could be minimalized not by a change in economic regime (as Marx claims) but by an existential change. Potentially, it is a very dangerous position, because any fundamentalist or fascist regime, any sect proves that it could happen. It is easy to justify any oppressive system, any social exploitative hierarchy, in this way.

However, if we start to think about dynamic hierarchies (plural), rather than a hierarchy (singular), then “total mobilization” could become a tool for radical “pluralization”. I combine total mobilization with inclusivity—from this perspective, total mobilization aims to include everything and everybody in a “diverse whole”. This links to industrial ecology: the idea of a world without waste.

You say we have lost the etymological meaning of the word “manufacture” (to make by hand). Fablab culture often channels the criticism received by the poor origins of products manufactured in the 19th century by the Arts and Crafts movement, which promoted trade skills, artisanship and handcraft. Could there be a risk of new “proto-industrial” capitalism in this contemporary fascination for micro-factories?

Any obsession, if taken out of context, is dangerous and/or silly. I am not part of the maker movement; I am not even so much interested in a re-industrialization as such. AI is coming, robotization is strengthening—these are unstoppable processes. As you mentioned earlier, neoliberal politicians are pretty excited about getting rid of the working class completely. The essence of the urban re-industrialization I am talking about is the idea of inclusivity, an attempt to (re?)create an urban community as a strong political and economical subject. Re-industrialization could help rebuild linkages and synergies already existing in cities, combined with a notion of total mobilization that could lead to a city as an inclusive society, where nobody is left out. This is also a society without waste. Urban re-industrialization is a tool, not an end goal. Re-industrialization is a political project.

“Urban Re-industrialization”, collection directed by Krzysztof Nawratek, published this spring by Punctum Books (PDF free download)