Kano demystifies computing for the 99%

Published 27 October 2016 by Elsa Ferreira

Alex Klein, 26, head of Kano, has already sold 100,000 DIY computer kits, federates a community of 82,000 people, and is launching a new range of tech objects to build and code yourself. Encounter with the young visionary who wants to give programming power to all.

London, from our correspondent

Rendez-vous in East London, “the door at the end of the bar.” In a large open space, where the rare desks are made from cardboard boxes, Makery met Alex Klein, 26, director of Kano, and his “gang of weirdos”, as he calls them. Weirdos, maybe, but who know what they’re doing. The UK’s fastest growing start-up, based in London, raised more than $15 million in May 2015 and has sold 100,000 DIY computer kits since its launch in early 2013.

“It’s a long-term project,” says Klein. “But what we imagined from the beginning was a creative computing system whose purpose is to give you control over the devices and apps that you take for granted day to day.”

The company is fine-tuning their latest line of devices—a camera, a speaker and a connected LED screen, currently in crowdfunding. But it’s their first product that built their reputation, a computer kit that “anyone can build and code.” Klein was inspired by his 6-year-old cousin’s desire to build a PC the same way you play with Lego, i.e., without having an adult to explain it to him.

“Learn to code, become a billionaire”

“The pre-existing world of the maker movement offers a box, a Raspberry Pi, wires, a breadboard. It’s very complicated. Let’s bundle all the pieces you need to wire the speaker, give power, give memory, give wifi,” says Klein. And especially, his team developed the “story book”, a simple and playful assembly manual. “A lot of people in tech think that the narration is the last thing to work on,” he observes. But for this former journalist, who has written for Newsweek, The New Republic, New York Magazine and Buzzfeed, “it’s just as important as the design.” Each page contains a drawing, two lines of instructions and an action to do. “You can eat an elephant one bite at a time,” Klein summarizes.

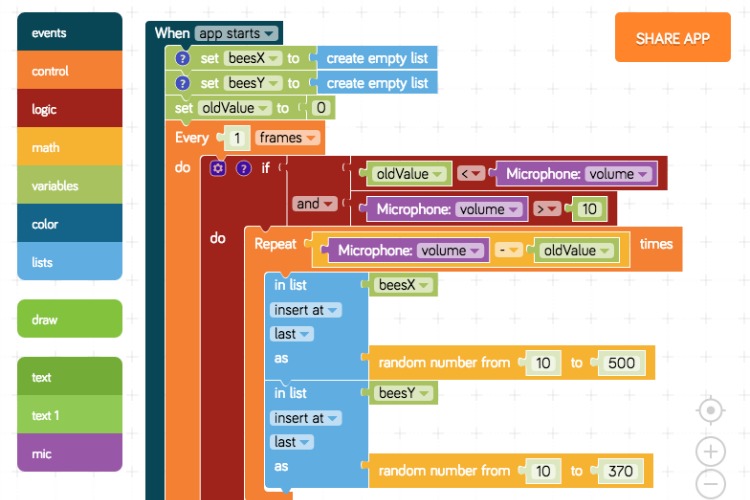

Once the computer is built, users can create their own programs in real Javascript using both block-based coding and text coding. “We break programming down into very tasty, intuitive parts. We show you what to do, we tell you.” This approach has earned the young CEO a nomination as one of Forbes’s standout “30 Under 30” innovators in both 2014 and 2016.

“The way we generally teach computer science is very traditional,” Klein says. “It’s about memorization, learning a particular language. With that approach, kids would get bored—anyone would get bored, really. The message is: ‘learn to code, become a billionaire’ or ‘learn to code or you will be unemployed’. Kids, especially if they are into games, art or music, are turned off.”

Caution Kickstarter

The company started off under a good omen. In 2013, once the first computer kit prototype was developed, Klein turned to Kickstarter. “We knew that this kind of community would be interested in this product. They’ve got an approach that blends art and science.” He needed $100,000. He raised $1.5 million in “one of the most successful Kickstarter projects of all time.”

“We had to build 15 times as many units, it was a huge challenge,” he recalls. “On the day that we were going to start shipping, we discovered that the battery inside the keyboard was not up to spec. That meant a delay of four months.” But Klein was well surrounded (his manufacturing director spent 20 years in China), and above all, knew how to be “transparent” with his supporters: “That is almost part of the product for backers of the crowdfunding campaign. They want that look inside the black box. And Kano is really about looking inside the box that is usually closed.”

How to build the Kano computer in 107 seconds:

The 13,000 backers received their kit. The Kano community has grown and expanded to 86 countries. More than 82,000 people now publish their programs on Kano’s community platform (“we call it the learning engine”), for a total of nearly 20 million lines of shared code.

The company has also grown, currently employing 50 staff of 22 nationalities, shipping to 38 countries and is available on Amazon UK and U.S. “The type of computer company we want to build needs to have a footprint on the crowdfunding platform but also on the retail maket, such Toys’R’Us.”

DIY photo filters and surveillance cameras

After opening up the computer, the entrepreneur is launching his line of physical computing “to make the invisible visible”—devices that interact with sound, data, motion.

There is Pixel Kit, a screen of 128 LEDs that users can program to respond to sounds or to channel online data to display a live Twitter feed or the weather forecast. (“Every day, we look at screens with millions of pixels, but we forget them because they are so close together you can barely see them.”) Then there is a camera that can be used for surveillance or creating filters. (“Why should Instagram have all the fun? People should be able to code their own alteration to photos.”)

Future product “made by you”

Alex Klein has a conviction. “The first PC revolution was about computers that anyone could use. The next PC revolution is about computers that anyone can make,” he writes to present his start-up. When pressed for details, he explains: “If you think about the 20th century, the progression of education and the massive transformation of the entire world has been through moving educational focus from learning a specific artisanal skill to reading, writing, arithmetic. We are about to go through a similar transformation, but in this century, reading, writing and arithmetic are replaced by computing, data, logic, control flow, networks. There needs to be a computing platform that brings that to people in a simple, human way. Because Apple isn’t doing it, Google isn’t doing it. Right now there is no playful way for your average person to get into this stuff.”

Indeed, if more than 2 billion people own a smartphone, less than 1% of the population knows how to program a computer (less than 50 million, according to a 2014 study by the International Data Corporation). Klein hopes that in the future, products will no longer be “designed by Apple in California, made in China” but made by you “or by people you know” with inexpensive tools running open software: “It’s a more ground-up, democratic way of making new products,” with “more diversity in how software works, feels, looks.”

“In the early days of the Web, it was the Wild West, with so many different kinds of content,” Klein recalls. “There were anarchic screeds, websites that would crash your browser. Today, it’s like everyone’s personality is constrained by these programs set by people you would never meet, people who control what we see and why. I think one of the reasons Brexit happened, one of the reasons we have a political convulsion going on now, is that we don’t understand as a people how the data on us is used to control the flow of our attention and serve us content that the algorithms know we will like, but that ultimately will not challenge us. The more people understand, the more they would question it. They don’t need to code an alternative to Facebook programs, they just need to be aware.”

Crowdfunding campaign for Kano’s “Physical computing for all”