Why a Paris suburb is replacing an urban farm with a parking lot

Published 15 September 2015 by Elsa Ferreira

Two months ahead of COP21, the announcement was particularly shocking—the city of Colombes, just outside Paris, wants to tear down the local farm R-Urban… in order to make way for a parking lot. Even as Agrocité, its recycling center, its composting school and its “reclaiming materials” workshops did more than pave the way for a resilient economy…

“If they had said that they were replacing Agrocité with a nursery school, I wouldn’t feel so sick,” says Catherine Béhague, Colombes resident who comes almost every day, often with her daughter. Seeing “her little corner” vanish to make way for parking spaces “just burns me up,” she confesses. “My wife feels the same way,” adds Jean-Claude Prévot, a man in his sixties with the verve of a former trade unionist.

The two locals were commenting on the latest (bad) news about the R-Urban (rural urban) project—a farm within the city, a coworking and educational composting space launched in 2008 by Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée (Urban Tactics) and financed by the European Union’s Life+ environmental program. Unfortunately, the new municipal government also has the right to forego this funding in favor of a vague (and temporary) parking project. The lease expires at the end of September.

At Agrocité, “at the foot of the tallest tower”, points out Constantin Petcou, social designer and co-instigator of the project, they harvest carrots and squash, gray water and rain water. At “reclaiming materials” workshops, they make objects and a canteen, once a week. Agrocité is far from being self-sufficient, but its objective is to first create a network and opportunities to adapt its way of life to urban resilience.

Connecting the networks of urban resilience

“There are the associations for maintaining peasant agriculture, the recycling centers, the shared housing… It’s all good and well, but each one is in its own network, whereas the problems are connected. If people come here to garden, listen to talks, watch screenings, cook, they all live in apartments with washing machines, their cars, their televisions… It’s a very consumer lifestyle, it consumes energy, and most of them work within the ultraliberal economy that they criticized the day before.” Hence, through R-Urban, Constantin Petcou and Dounia Petrescu wanted “to create an urban resilience movement carried by the local residents”.

A few blocks away from Agrocité, they set up Recyclab, comprising a recycling center, a professional studio, a coworking space and a residency space for passing designers, architects or urbanists. Agrocité also includes a composting school, a “cooking collective” and a beehive (currently threatened by contruction work). Temporary, but resilient, employment.

There was also supposed to be a nearby residential unit, Ecohab. They found a vacant lot and had signed an agreement with the old city government. But the new administration, elected in March 2014, will not ratify the project. The lot remains vacant.

Vague projects and temporary parking

R-Urban failed to convince local officials. “I did everything that is humanly and honestly possible for an elected official to try to find a solution,” says Samuel Métias, deputy mayor in charge of sustainable development, green space and waste management, claiming to have addressed the department, the region and even the secretary of state in charge of sustainable development—in vain.

The city insists that the space is needed to accommodate a temporary parking lot, replacing another one that will close for construction. Agrocité must yield the land, but where to go ?

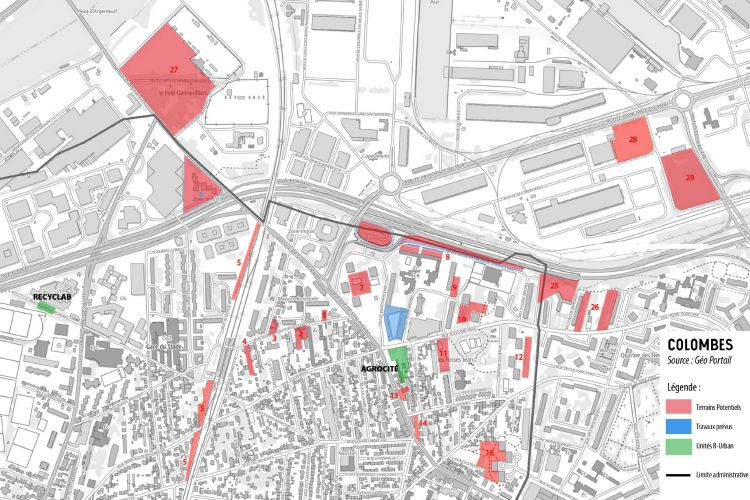

R-Urban members mapped out vacant lots in the vicinity—also in vain. “We identified 25 lots linked to the city. Their response was incomplete,” says Constantin.

Dialogue seems impossible between the association and the city. “The project is interesting in the sense that it educates people about ecology and sustainable development. It really attracted a lot of international attention,” persists Métias. “But as far as the residents of Colombes are concerned, it didn’t quite achieve the impact we hoped for, even if some people are invested.”

“There’s friendship, sharing…”

“About a hundred people bring their waste here,” retorts Yvon Pradier, “master composter” at the composting school. “I’ve already learned how to garden,” adds Catherine. “And the more people who come, the more friendship, the more sharing of ideas, knowledge, culture.”

Since Catherine has been coming to Agrocité, she has started sorting her garbage and talks about urban politics. “The difference with this project is that it’s not set up in a creative neighborhood,” points out Gabriel Wulff, a doctoral student in urban farming. “It’s more ambitious than preaching to the converted. Users’ vocabulary has changed, they talk about the politics of space, search for ways to live differently, they invest themselves wholly. They know how much energy it takes to grow a tomato and look out for seasonal vegetables.”

Seoul, Montreal, London… and Colombes ?

To stay, or not to stay ? Constantin still hopes to find a common ground with the city—and plans to appeal to European institutions. The cities of Seoul, Montreal and Berlin have expressed interest, while a project has been co-developed with London.

All the better, as multiplying local movements to address a global problem is also R-Urban’s objective. But Constantin would like to keep this project in Colombes or its vicinity : “We haven’t just created physical equipment. We’ve created a dynamic of participative resilience by instigators of local projects. We’re trying to save that with them.”

Sign the petition to save R-Urban