Walking the questions: A slow journey in a three-piece business suit

Published 4 January 2024 by Monique Besten

Earlier this year Rewilding Cultures initiated a conversation to rethink mobility and cultural exchange by offering a Moblility Grant. Monique Besten was one of the recipients. Here is her report.

What is my territory? What is yours? What does belonging mean? What do you truly own? Where is the wild? How to listen to non-human voices? What is the power of slowness? The best way to answer questions is to live them and in order to do that I went on a slow journey with simple means through northern Spain from my home in Barcelona to The Foundry in Galicia, 6 weeks mainly on foot, moving attentively through the world to encounter people, places, none-human beings, to find new stories and new questions.

The Foundry in Galicia is a non-profit space for artists, writers, artisans and other creators who seek to work outside of the institutional confines of market and university. Against the abstraction and commodification of creative and intellectual labour, the site stresses that critical thinking is a way of living rooted in engagements with one another and with the environment. The Foundry is a collective and self-organised project, where everybody is welcome, and all are using and taking care of a shared space in a non-hierarchical way. I was supported by Rewilding Cultures, a project that wants to reposition the wild after COVID and focus on inclusivity and ecology within the art, science and technology area: “We cannot go back to business as usual, especially in terms of polluting and important inclusion issues unaddressed. We need to rewild on terms fit for the present and future.”

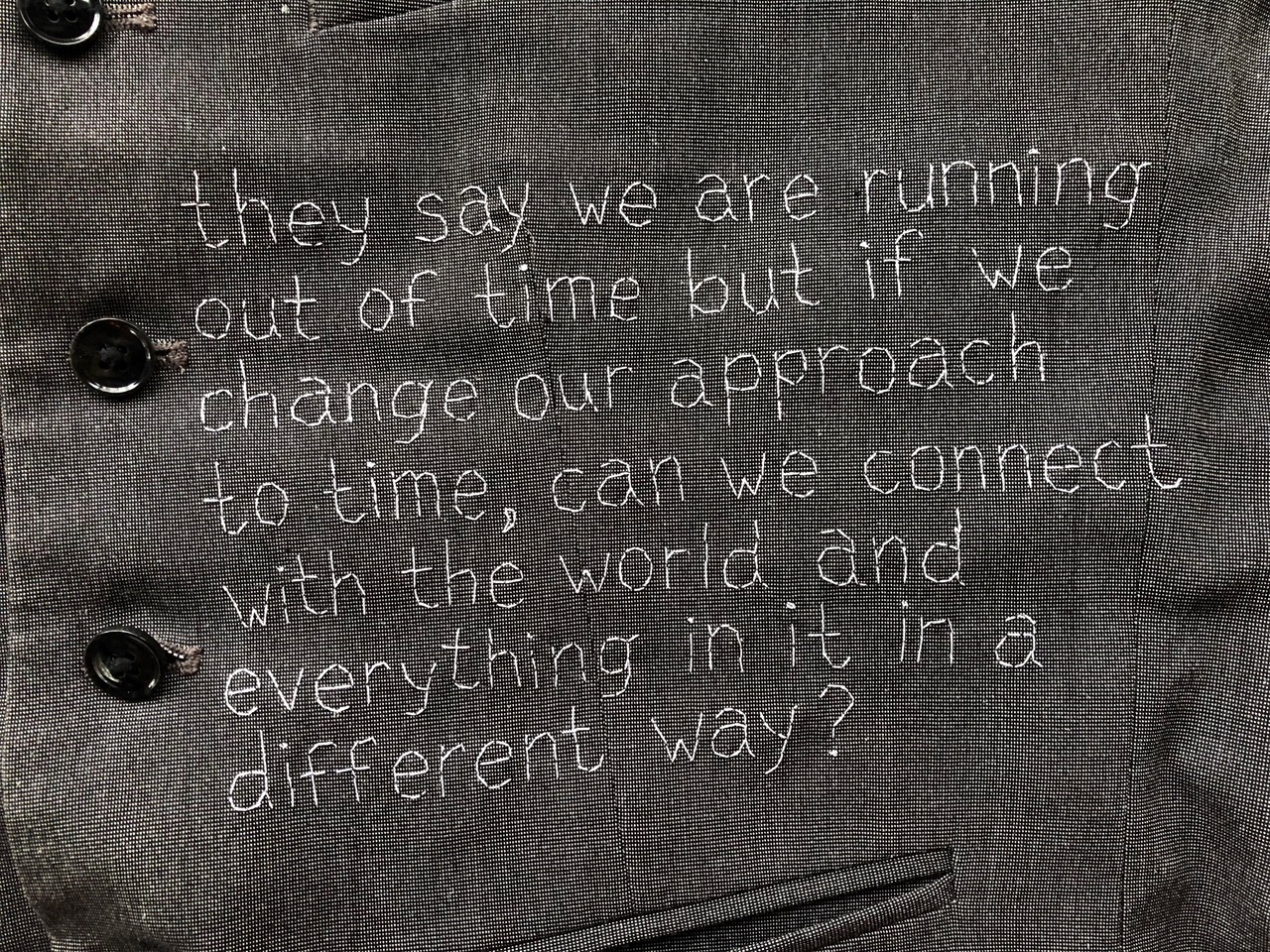

I walked in the three-piece business suit I had worn daily for a year and embroidered with questions people asked me through calls on social media or when encountering me walking around in the suit. The suit gives the walk a performative aspect and in every new walking project in a suit (this is nr. 8) new meaning is added to the body of work. It addresses ecology, politics, gender issues, capitalism, the outside versus the inside (how we deal with appearances), the history of walking and many other things. While walking the questions around, I collected new ones and engaged in conversations with people I encountered. Although there was one question central to the walk: “How do you inhabit a territory?” it wasn’t the most important question. All questions were equally important and every question was connected to the other ones somehow.

What is your neighbours name? What is success? How much is enough? How do you grow things? What matters most? Which border would you never cross? I had some answers but finding answers is never more important than living the questions: “Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer” (Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet).

I left with, or in a question. The man I asked to take my photo after I stepped out of the hallway of my house into the street on a hot summer day in the second week of July said: “Isn’t it too hot to walk?” “Yes”, I said, “and if we don’t take care, pretty soon it will be too hot to live”. I didn’t know then that July 2023 was going to be the hottest month ever recorded on Earth – and likely the hottest in about 120.000 years. It was definitely the hottest day I ever experienced when a week later I walked through Aragon in 46 degrees. At night the temperature didn’t drop much below 30 degrees and the mosquitos were ruthless. The land was dry, apart from areas where fruit was produced and water flowed as if it was in unlimited supply. The fruit was inedible: it gets picked when it is still unripe and arrives in the supermarkets still hard as a rock because that way it can be sold longer. The workforce consists of immigrants mainly: I saw them being brought on open wagons to the fields, wearing sweaters, clearly being used to temperatures even higher than the ones here.

It was hard in the first week to get through the network of roads running through the most densely populated part of Catalonia. Spain was the last country in Western Europe to experience depopulation and the remnants of an ancient infrastructure are still there, but like in every country, the areas around big cities are dominated by cars, highways and railroads. I walked through river beds, along highways, passed through villages, sometimes retraced my steps and took detours when it became impossible to stay on a busy road. To not plan ahead was part of the undertaking. In a society where everything is about progress, about reaching goals as quick as possible, taking shortcuts and aim for the biggest gain, being slow, improvising, go with what the world puts on your path, taking time, feels like a revolutionary act. Walking in a business suit has been interpreted like that as well, although the first time I walked in a suit it wasn’t because it is a capitalist symbol: it was because I had read that when people started wearing suits they were— and still are—called three-piece walking suits, often worn as leisure clothing. I wanted to find out if something that is called a three-piece walking suit is still suitable for walking and it is, if you don’t mind it getting stained and worn out. In the first pages of Walden, Thoreau wrote: “Perhaps we should never procure a new suit, however ragged or dirty the old, until we have so conducted, so enterprised or sailed in some way, that we feel like new men in the old”. The best thing about wearing the suit, my costume and uniform, is that I can be anybody in it and it invites other people to approach me and start conversations.

On a long walk out in the world, everything has equal value. Wandering through a city is as important, as educational, as wild, as wandering through a forest is. An encounter with a person isn’t deeper than an encounter with a plant or a stone. The dead are there as much as the living. Good and bad are abstract terms, as are beautiful and ugly. There is no way to avoid civilisation – even when you are in the most remote untouched part of the world it is still part of you, the human that was raised in a specific way—but you can be there, or at least try to be, on your own terms. Bend the rules, listen to what your instinct tells you, avoid being effective in a capitalist sense, act slow and without planning, interact with none-human beings. Be the nature you are. Every moment is lived, tomorrow is of no concern, a week is an eternity.

Some memorable encounters, but there were many every day: noisy cicadas in the trees in the middle of a big city, 86 year old Lolita who walked with the tread and smile of a little girl, a group of curious wild boar making me climb in a tree in the middle of the night, calendula plants the morning after a painful fall, a man making a living on the street sharing his lunch with me, vultures flying low over my head in temperatures of 40+ degrees, a little cave with a sea view on the last night outside, little children reenacting the running of the bulls, the habitat of Neanderthals, innumerable pebbles creating the most magnificent sound where a river met the sea, a kind man who opened his house to me and turned out to believe animals have no feelings and climate change doesn’t exist, a deer crossing my path on the outskirts of a big city just as I was overwhelmed by the amount of Compostela pilgrim signage and wondering if I had taken the right decision to follow this route, a shop employee gifting me juicy peaches, a small pond on a hot day, a park dedicated to the memory of abandoned villages, a group of pilgrims spending half an hour on their phones to find the best restaurant in a village you could walk through in 10 minutes, mountains watching over me, the locals in a roadside bar who welcomed me like a friend, a fox getting so close I could almost touch her.

I walked through Catalonia, Aragon, Navarra, la Rioja, Castile and León, Asturias and Galicia. The majority of the nights I slept outside, in forests, orchards, old barns, fields; there were days when I was tired in the evening and aimed for a place with a proper bed or a campsite with hot showers and undisturbed sleep but couldn’t resist the landscape and found myself walking on, to be able to wake up with birds fluttering in the trees and a mountain view and to search for wild greens and fruit for breakfast.

It was never in the first place about arriving somewhere, but at some point I was almost at my destination. It is one of the strangest moments in a long walk, having crossed mountains and plains, having met hundreds of people, having slept in the most comfortable and uncomfortable places and then one morning there are only 36 kilometers left, 25, 13, 7, 3, 5, 3 (how on earth did I take a wrong turn in the last couple of kilometres?) and there it was, a former iron works in the middle of a small valley.

In a way it didn’t feel different from arriving at any of the other locations where I arrived after a day of walking, I guess I accomplished something by getting to a place after roughly 1400 kilometres of which approximately 700 were on foot. Still the distance is a side issue, it isn’t about achieving a walk, a slow journey, it is only a way to be. To be at, to be in, to be close to, to be under, to just be. Now I was here, to meet new people and be part of a week long programme about Territory Beyond State and Property.

In-between lectures and workshops about different ways of commoning, symbiotic relationships between nature and human systems, fermentation, the car as a main driver and embodiment of the Homogenocene, presentations by the Ukrainian residents of the Foundry, communal work in the garden, film screenings and book presentations, I shared the first impressions of my journey.

What was most important was the walk itself, the subtle performance in which the people I met were just as much my audience as I was their audience. What remains are a lot of invisible traces and stories about the time we spent together that are memorised and possibly retold in other settings. Some stories, thoughts, images, have been published on the weblog about this project—mostly during the walk, so I was present both here and now but also everywhere always through the world wide web—and more in depth writing will happen in the future. The project has been nominated for the Marŝarto Award 2023 for exceptional walking art (the winners will be announced in 2024).

More info and more detailed stories here: https://asoftarmour8.blogspot.com/

Monique Besten is the recipient of a mobility grant awarded as part of the Rewilding Cultures cooperation project co-financed by the European Union’s Creative Europe program.