Soil Assembly at Kochi Biennale: food transportation, climate change and ocean trades (2/2)

Published 4 May 2023 by Tim Boykett

At the Soil Assembly – 1st to 5th February 2023 at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India – the panel discussion on ocean trades showed what is at stake with the transportation of food, along with the low-carbon alternatives, present and future. Tim Boykett from Time’s Up argued that alternative fuels, increased efficiency, and better routing systems are not enough to address the fundamental problems of our current transport system. To offer a tangible solution, Boykett presented six currently operating cargo sailboats and several upcoming projects around emission free transport that are currently being developed. He also examined the potential for setting up a sail cargo trading network around the Indian ocean. Boykett extends his reflections in this essay (part two).

Last week we talked about and reflected upon a range of ideas from Soil to Sail based upon the talks and reflections from the Kochi Biennale Soil Assembly (read the part one here). The interconnectedness of soil and sail, of empire and extraction, producers, traders, merchants and consumers and their interplays with culture and the arts, are a dance and an almost invisible force field that reaches back centuries.

Soil Sail Scenarios

Most of the transport undertaken by existing sail freight organisations are foodstuffs. Notable exclusions are the Vega, transporting aid to remote islands in the Indonesian Archipelago, the Grain de Sail transporting aid from NYC to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and the first journey of the Tres Hombres, which transported aid to Haiti. The Avontuur has transported an electric car and there are reports of some smaller, non-food-based transports.

The Canopée will transport rockets from France to French Guyana for European Space Agency launchings; it is certain that more such projects will emerge as wind power becomes more acceptable to shipping companies. The emergence of large scale windships could fit within many scenarios; from the collapse/discipline world of The Windup Girl to the continuation style scenarios that pervade the literature of Neoliner and other large players.

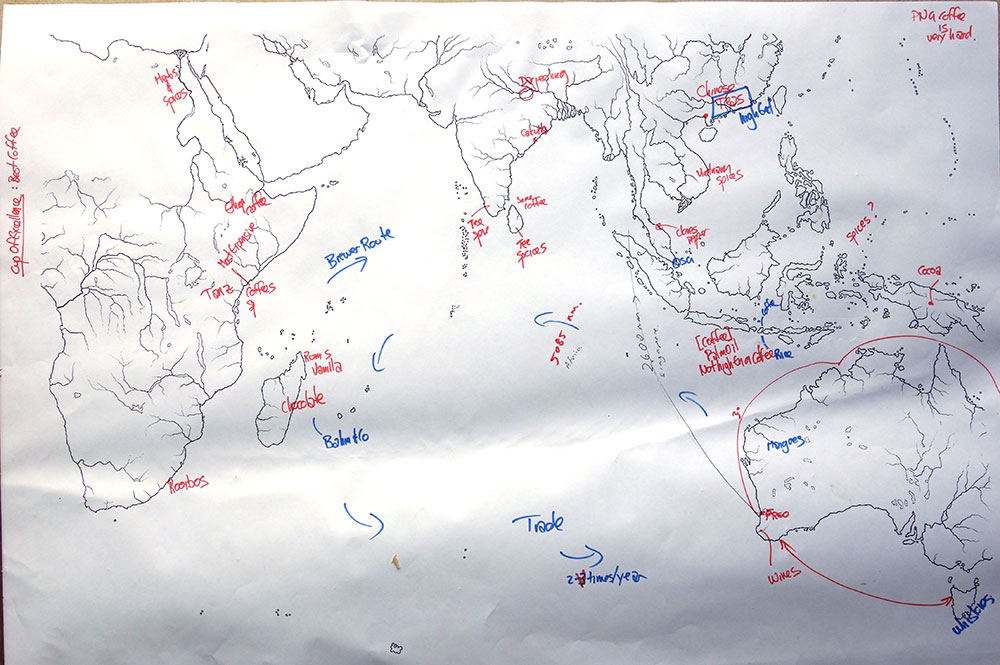

If we think about the convergence of situations like the Sarjapura Curries project (see part 1) and small windships, one arrives at something like networks of small farms, growing local, seasonal crops and exchanging certain crops and resources through networks of small vessels. Steve Woods at the Hudson Maritime Museum has undertaken investigations of the necessary shipping resources needed to supply various US American cities with their necessary resources; there is reason to support the idea that medium sized schooner style vessels are the right size, the appropriate technology, for such a scenario. Around the Indian Ocean there are a number of regions with distinct production profiles, from the large open spaces of north western Australia, the rich islands of the Malaysian-Singapore-Indonesian-Papua New Guinea archipelago, the Himalayan watered lands of the subcontinent, the arid dunes of the middle east, the eastern coast of Africa down to the richness of Madagascar. With Sayapura style focus on regionalism, the effects of Bioregions will be strongly felt and the benefits of trade and exchange across these bioregions will be beneficial to all. Ricardo’s analysis of trade seems to indicate that specialisation is better for all; we know that this is not completely true as his analysis ignores the transaction costs of transport as well as the risks of fragility and being prepared for instability, both forces that suggest that self-reliance at a regional level is a good thing. Nevertheless, the trade of valuable resources, local specialities and other goods has a lot to offer on a quality-of-life level. The creation of peer-structured exchange networks is a fundamental challenge here. How are we to ensure that the errors of colonial behaviours are not replicated in the creation of new networks? Learning from feminist, post-colonial and other economic reflections and analyses will be vital in order to imagine these scenarios coherently.

Such scenarios might fit inside a Collapse scenario with small vessels running the gauntlets of pirates and rapacious “customs” officials from warlord strongholds, or just traders bringing spices and insulin across the seas from the places where they can still be produced. It might be a Transform scenario of radical collaborative sufficiency and peer exchange. Or a Discipline scenario where fossil fuels are strongly regimented, so fossil fuel free transport becomes one of the few possibilities. It is not particularly compatible with a continuation scenario, where the process of growing structures of hegemonic power and centralisation lead to economies of scale and conformity, with every town having the same supermarkets.

These scenarios are but sketches and imaginations of what could be possible. Within the bounds of today’s economic realities, it is hard to gain insights into how these might operate. Even testing them is hard, as we witness with the various operating small sail transport enterprises that are operating now. Some of the techniques that arise lie in the realm of prefigurations, borrowing from the radical activist ideas of creating the new world in the shell of the old. Artistic and cultural practices of prefiguration, in particular FoAM’s processes of Prehearsal allow experiments to be undertaken that offer insight into not only the scenario summaries but also the lived experience and subjective feelings of a certain scenario. With words such as subjective in the mix we can be certain that there can be no analytical reflection; all our evidence will be necessarily anecdotal and personal, unreplicable.

More entrepreneurial approaches are perhaps a little more objectively analysable, such as José Ramos’ Anticipatory Experiments, where activists attempt to built safe, small, short time frame, simple and shareable experiments in order to investigate the possibility of changing practices or developing new practices in order to respond to a situation and test an emerging scenario. We would claim that Sarjapura Curries is exactly such an anticipatory experiment. Or a cultural prefiguration. It is both cultural, subjective, experimental and anticipatory. Rather than crying for help, it creates a fragment of a desired future in the shell of the old, in this case, as a micro farm in a town.

The Danube Clean Cargo project also took such an approach, imagining and then building the structures to run regional fossil fuel free food transport along the Danube River. The Vermont Sail Cargo project from 2013 was closer to an anticipatory experiment, with a farmer as the instigator, bringing a selection of products down from the upper reaches of the Hudson rive to various ports all the way to New York City. The Maine Sail Freight project in 2015 was similarly designed as a public facing cultural experience; not necessarily to run a pilot of a possible sail freight network, but rather as a cultural exploration of the possibilities and cultures of sail-based freight and transport. As Fleming says, it was also designed as a pageant, an exploration as a very public and extravagant show of possibility. Both these last projects were, in some way, experiments that “failed” according to many measures of success, but they were experiments and cultural experiences that opened a glimpse into a possible future. The Apollonia schooner that started operating along the Hudson in 2020 is the entrepreneurial child of these projects, offering a commercial service that is growing and beginning to make its way in the world.

The case can be made that shipping foods only makes sense across bioregions. Bioregions are defined by the intersections of rainfall, temperatures, winds, soil types, land forms and other aspects of biogeography. Similar bioregions allow the growing of similar foodstuffs, the idea of climate analogues being a favourite learning connection between similar bioregions separated by large distances. Similarly the human structures and social environment in similar bioregions are often similar. Between Scotland and Norway there is little difference in what grows, thus there is little need for transport, unless one focusses on localised specialities (haggis and whiskey traded for fermented fish and aquavit?). However, the movement of foodstuffs between the UK and Portugal, a comparable distance, is useful because they are in distinct bioregions. As a result, the exchange is beneficial to both parties, bringing something that is difficult to produce in one region from another. This contradicts, to some degree, the ideas of David Ricardo and the theory of comparative advantage, which underscore the benefits of trade in spite of local benefits.

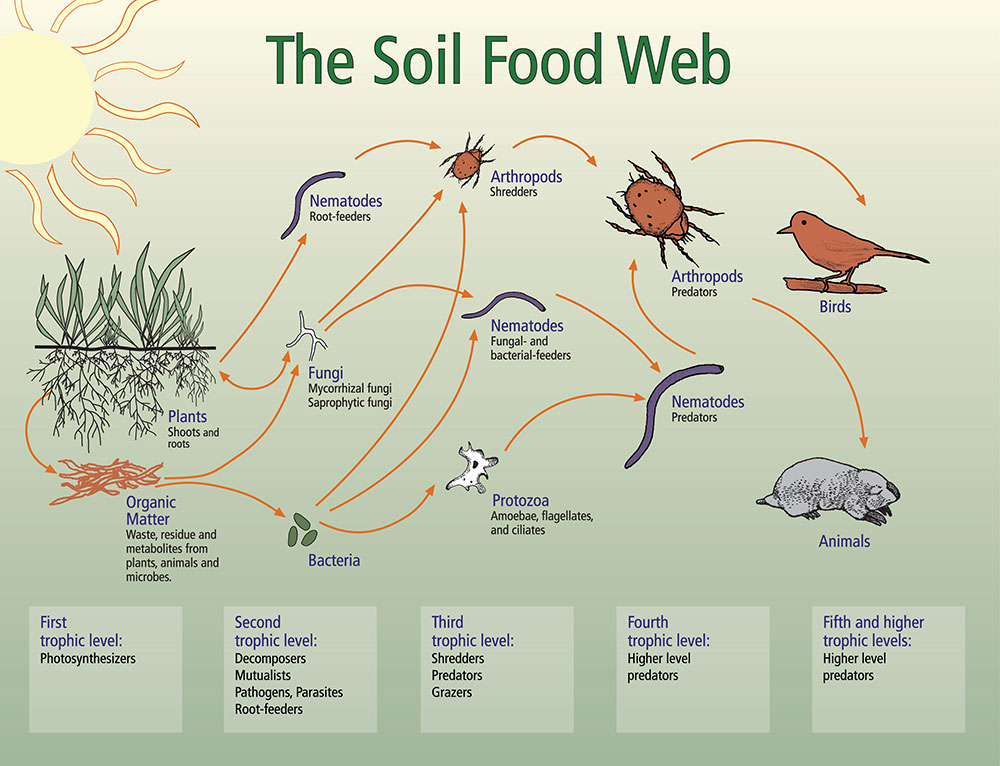

These networks connecting different bioregions cannot help but remind us of the Soil Food Web as discussed by Elaine Ingham and others. Early agricultural science apparently treated the ground as a dead substrate with more or less accessible nutrients. Soil = Dirt + Fertilisers. This is the core metaphor of what is known as the Green Revolution, which should perhaps be better known as the brown revolution of fossil fuel powered industrial agriculture. This revolution turned farming into industrial infrastructure. In the intervening decade our increase in the understanding of the soil as an ecosystem of roots, fungi, nematodes and a wide variety of other animate and inanimate life forms, each of which plays a role in the recursive flows of nutrients and energy, reminds us that permacircular systems are a case of mutual exchange. Each organism in the network gives and receives material that is transformed but never becomes waste. Earlier farming techniques accepted the role of “nature” as a part of their soil and support, not invisible infrastructure, but as a visible part of the process. In fact, it is arguable that nature is a nice word for a certain type of infrastructures, the stuff that we want to have “over there” and not worry about except when we want to have a walk in the woods. As Timothy Morton keeps reminding us this treatment of nature is perhaps the problem; nature, like infrastructure, is part of use and we are part of it.

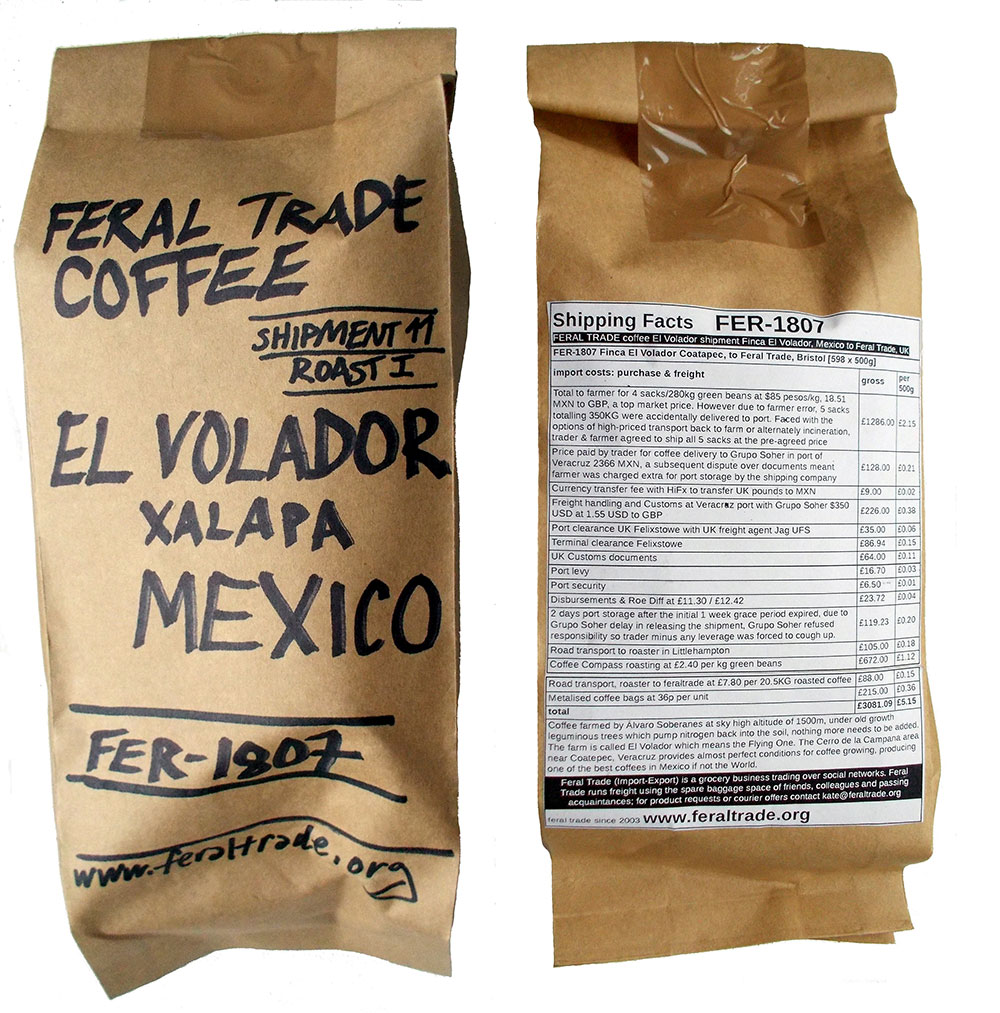

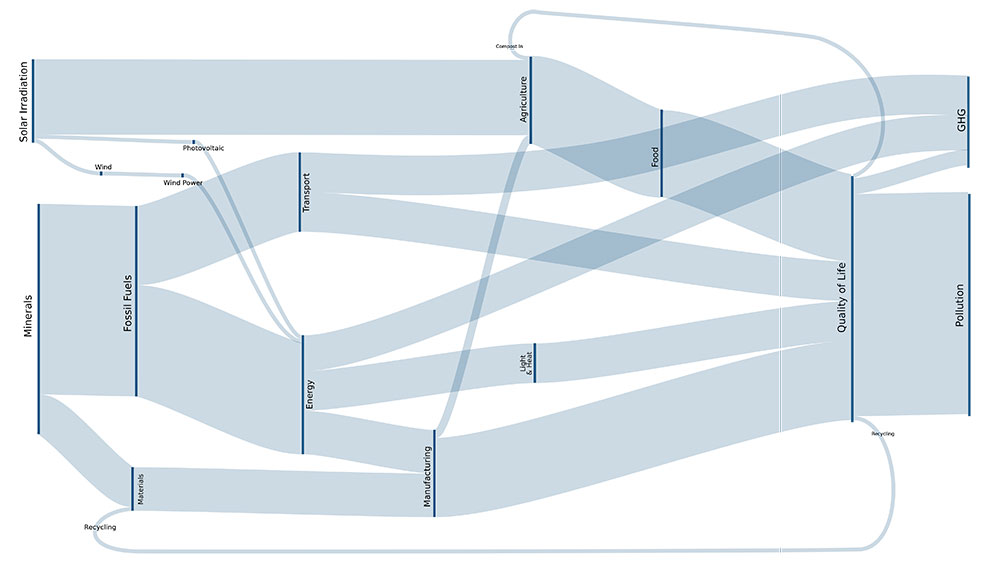

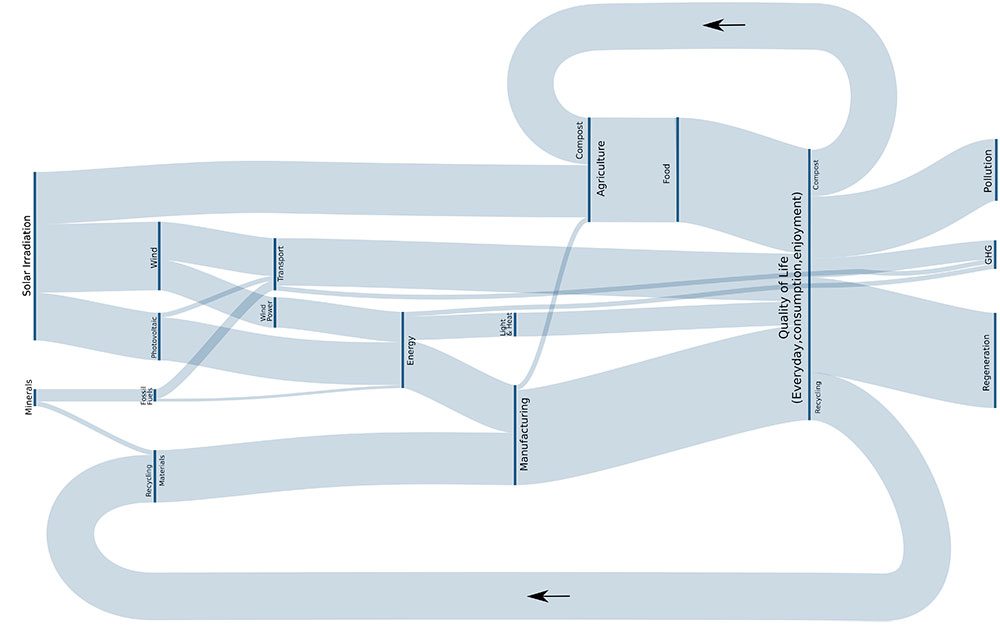

The circular economy 2×2 analysis that we saw in the first part of this essay also indicates that, if there are no technological solutions, then we will need to stay in the lower left corner, the permacircular corner, accepting the boundaries that nature as visible infrastructure imposes. We will need to be aware of and accepting of, the network processes and transaction costs within the whole delivery chain, as part of a logistics and exchange network. Feral Trade do this well with the costing label on their bags of coffee. Transparently sharing the steps and costs of those steps to every consumer of their coffee, they make the network open. Such examples of art meeting radical openness are valuable insights to how the world works and perhaps how we could go about creating more understanding and clarity in our lives.

http://feraltrade.org/ (Image source: Feral Trade / Kate Rich)

The foodstuffs in trade networks of fair trade and clean transport are generally luxury foods. Foods that are dense enough that the costs of transport are not overwhelming. This has to do with sharing the cost. Andreas Lackner from Fair Transport in Den Helder has noted that the price of sail transport on a bottle of wine was around one Euro. For a cheap bottle, that is a considerable extra cost, for a luxury bottle the extra charge is more or less inconsequential. As people note with organic food, the extra cost probably reflects the actual real costs of producing that food compared to the artificially cheapened costs of producing food with fossil fuel derived fertilisers, high tech seeds and fossil fuel driven mechanisation. Similarly the cheapness of transport does not reflect true costs, as we are ignoring many of the costs that are externalised onto the environment, both physical and social, with heavy fuel oil poisoning the air, water and land and cheap seafarer’s labour poisoning social relations. Shipping is part of the extractivist mindset.

Lackner’s comments reflect the focus of the main sail freight companies on high value density goods, which equates more or less to luxury goods. Rums, whiskies, wines, cacao beans, coffee, Panela sugar; the list of goods reads too much like the freight list of an 18th century sailing ship returning to Europe at the and of the run that took textiles to Africa, slaves to the Americas and brought commodities for European consumers back, to create the profits that built Europe. With the lack of peer structures, there is nothing that cacao farmers in the Caribbean would want to import from Europe in order to have a balanced trade. Perhaps this is an indicator of the imbalance that is indicated in the expression extractive?

https://timesup.org/activities/everything-else/better-sleep-worth-it

https://timesup.org/activities/exhibitions/work-upside-down

Nevertheless, another framework is possible. The Apollonia transports grain, malt and beer along the Hudson. These are not luxury goods, although they are probably not the cheapest and most commoditised versions of these goods that are being transported. The Apollonia also calculates shipping costs by replicating the costs of shipping by truck. There is no extra charge for clean delivery. The ship Undine operating between Hamburg and Sylt was also as cheap as or cheaper than truck delivery, the ship Lo Entropy currently being refitted will offer a similar service. The Apollonia is still having trouble filling its hold for the return leg from New York City up the Hudson river, but the balance is slowly coming about. As the Vega Gamleby starts bringing Columbian coffee to New York City in 2023 there will be more products to ship upriver. There might be the beginnings of a peer-to-peer trade network emerging, even if it is partially dependent upon the input of coffee being brought in from afar.

The sketched Indian Ocean network that was alluded to above has looked into this and there seems to be an indication that products could be on- and off-loaded at (almost) every port of call on the way around. The age old trading networks across the northern Indian Ocean, from the archipelago and China to Madagascar indicate that there was value in bringing small quantities of cherished goods across the ocean. Trade is a balanced relationship, and empowers upon many levels when done right; so much so, that calls for “Trade, not Aid” are heard repeatedly.

Sailing to Kochi

It is perhaps worth noting that this transport network in the Indian Oceanwas also used for bringing passengers, whether migrants or those devout persons making a pilgrimage, explorers or entrepreneurs. Which brings us to another point of discussion and an exploration of possibility. If, in some future scenario, the use of fossil fuels for flippantly flying to Kochi for the Biennale from one’s basis in Surinam, Provence or Surabaya is too hard, how else might one get there? In this context, the question of Sailing to Kochi arose. Some arts and cultural practitioners such as Rob La Frenais have already stopped flying, noting that they have certainly used their lifetime share of CO2 emissions and needing to reign themselves in. Others are interested in the exploration of this question: what would it mean to transport artists and artworks to and from physical events such as the Kochi Biennale, by ship?

The ease and simplicity of a flight from one’s home base to some hub like Singapore or Doha, then an onward leg to Kochi is hard to match. The first world problems of jetlag arise as does the question of excess baggage with which to transport all the bits and pieces of an artwork to be exhibited. All in all, the travel would probably be complete within not much more than 24 hours and one could recover from any inconvenience in a hotel room.

Replacing this with a shipping route is nontrivial. Hitching a ride on a container ship or other freighter was once regarded as a somewhat decedent thing to do, but has become more difficult since the Covid situation exploded. While the extra contribution of fossil fuel consumption for a few people on a ship transporting tens to hundreds of thousands of tonnes of freight in containers is negligible, the emissions are still there and are significant. Ocean going transport contributes around 2.6% of the world’s fossil fuel CO2 emissions, ignoring the other pollutants such as black carbon, sulphur and nitrogen oxides and heavy metals. It is clear that the only efficient or effective way to do it would be to use a sailing vessel. The route around South Africa is fraught with danger, so only the route through the Suez Canal remains as an option. The danger from Somalian pirates has apparently decreased and the war in Yemen is probably only a danger if one tries to dock there.

Bringing in the expertise of Geoff Boerne who took his sail cargo vessel Lo Entropy through the Suez Canal and Red Sea to east Africa in 2009, the time required would be something like 8 weeks, perhaps a little less for artists embarking in the Mediterranean. But then we realise one of the benefits of such a project: what if the journey did not only bring a group of artists from Europe but collected a number of participants and artworks along the way? The possibilities begin to grow: a group of passengers on a vessel form a temporary community. By all heading to the same destination, they are in some form intentional. On board such a journey, there are ample opportunities for exchange and learning. This has been used extensively by the Sail Training movement, various youth rehabilitation groups as well as the trainee part of the nascent sail transport companies. Christiaan de Beukelaer talks extensively and with great honesty and sensitivity about the social relations among the crew of the sail trading vessel Avontuur as it was stuck en-route in 2020 as Covid closed down the possibility for crew changes or even time on land.

Using the time on board to create a mobile symposium, a learning environment, a creative forum of some sort, offers itself as a way to use the time productively and enjoyably. Could this be an anticipatory experiment or a prehearsal of a post-fossil-fuel world?

Be careful what you ask for

One of the emerging questions is then: what happens when this is successful? One of the selling points of sail cargo has been the story; this rum was sailed across the ocean, this beer was sailed down the Hudson, I bought this oil from a sailor in the harbour. As Sail Freight becomes commoditised and less newsworthy, will it continue to hold value and novelty? While the first slew of sail cargo vessels were all traditionally rigged and run by a large crew actively pulling ropes, probably to the tune of sea shanties to coordinate them, vessels such as the Grain de Sail are modern vessels, easy to run, with small professional crews and palletised cargo. The emerging larger projects, whether from TOWT or Neoline, begin to turn sail freight back into infrastructure: regular sailings, commercial rates, frictionless (or at least low friction) processes. Will Lackner’s extra euro per bottle still be part of the cost-benefit equation? Or will this become another part of the network that includes places like Suresh Kumar G.’s small art farm, a bottom up, small farm future fragment? There is a dilemma here, as the creation of infrastructure makes life simpler and enables many to specialise and become cultural producers and researchers, but also extractive entrepreneurs. How will we, as creators of culture, continue to deal with these questions?

Read Part 1 of this article.

Read our articles related to The Soil Assembly

Visit the Soil Assembly website (complete videos of the presentations and panel discussions).