Green Open Food Evolution, a speculative exploration of algae and the food transition

Published 20 October 2022 by Pauline Briand

Swiss artist Maya Minder’s “Green Open Food Evolution” installation was inaugurated as part of the group exhibition “More Than Living” at the Open Source Body festival at Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. It will also be presented at Rencontres Mondes Multiples by Antre Peaux in Bourges from November 19 to December 4, 2022.

At the opening of “More Than Living”, visitors gather around a sinuous table whose sunken craters are occupied by vases filled with a blue-colored beverage, bioplastic plates holding seaweed-wrapped maki rolls, small mounds of algae-seed granola, plus a variety of sauces, algae and fermented vegetables. During this performance banquet, food is eaten with hands, bioplastic containers are partly devoured. The desserts are served in Petri dishes holding bits of fruit imprisoned in the same agar-agar, a jellifying substance derived from algae, as in laboratories for microbiotic cultures. On the periphery, a wooden drying rack exhibits long dried seaweed, bioplastic forms containing plant fibers or animal hairs, kitchen utensils with both strange and familiar forms, Petri dishes seeded with microbiota of organisms belonging to various kingdoms, in colors ranging from blue to pink.

Green Open Food Evolution (GOFE), the culinary installation conceived by Maya Minder and her collaborators, has come to life. We met the entire team before the opening to discuss this project at the intersection of art, traditional and digital craft, cooking and research.

Eating to invent the future

Maya Minder introduces herself as an artist in “eat art” – a versatile expression that could translate as art mediated by food, but also the art of feeding oneself. Her artwork takes the form of installations that host various living processes. “Gasthaus – Fermentation and Bacteria was my first project. There was also a table in the center of the room, microbes were developing on top of it in the form of various ferments such as kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha, kefir. I use this metaphor of fermentation as a reflection of social agitation. In the 21st century, we are starting to realize that the idea of community must be lived and reinforced. Within communities, you have social democracy, you have the platform of assemblies, you have to negotiate. It’s pretty to similar to a bacterial process. As the kombucha develops, bacteria communicate with each other, and at the turning point, they produce a new biofilm. Just as we do when we create great collaborations.”

The GOFE project, which came directly out of this practice, launched in late 2020, when Ewen Chardronnet invited Maya to join a work-in-progress on algae in partnership with the Roscosmoe program and the Multicellular Marine Models laboratory at the Roscoff Biological Station in western France. The two artists then co-developed a speculative research that explores the concepts of symbiosis, planetary interdependence, and algae as food and a key actor in the ecological transition. Their work is based on the research of Xavier Bailly from the Multicellular Marine Models lab on Symsagittifera roscoffensis – a local autotrophic marine worm that in its juvenile stage ingests microalgae without digesting them, keeping them in its epidermis and feeding off their photosynthesis. They are also inspired by the Roscoff Biological Station’s research showing that Japanese people’s consumption of seaweed over time led to a horizontal gene transfer that modified their microbiome, as well as the ideas of evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, who speculated on a future “Homo Photosyntheticus” – the human version of the Roscoff worm.

Maya Minder explains: “What if humans became Homo Photosyntheticus? For me, this narrative is both utopic and dystopic, because I like to cook, and becoming autotrophic would mean no longer having to eat. By imagining what humans would be like in the future, you also start to think about the human structures of our domestic world – how much energy we use, all our animal food and this whole industry that we create around food. I’m stepping back, in order to create a bigger space for imagination.”

Several questions emerge from this narrative. How do we feed a perpetually growing population? What would be the recipes, gestures, practices? “I’m very much inspired by Filippo Marinetti’s ‘futuristic cuisine’. With GOFE, we apprehend food like a playground, a means, not only to feed people, but also to create discussions and speculate.” Maya also questions how food changes our bodies: “I speculate on the way in which the daily ingestion of food changes us, the action of fermentation on our microbiome, the link to the place where we live, the role of the microbiome that is specific to the hands of the person who cooked. In Korea, we have the term ‘son-mas’, which connects a person’s hand to the taste of their cooking. When I give fermentation workshops, I say ‘Let’s mix our microbiomes!’”

Cooking to resist the system of productivity

“Family cooking is holistic in the sense that it’s about sharing love, taking care of food, managing one’s time and resources, like the amount of land that we need. And it’s about becoming aware of the origin of your food. Food that you cook yourself is the best approach to get people interested in participating in this dialogue of food transition.” Indeed, this transition questions the amount of energy required to produce the food, the place given to meat, global food chains.

Lisa Jankovics, the chef who supports Maya in her creations, adds: “Working with Maya has changed my relationship to time, I’ve slowed down. Fermentation requires you to take your time. You initiate the process, it will deploy over time, but you can’t totally control it. It’s a vital process.” For Lisa, eating with your hands is also important: “It’s imtimate and intense, you pay much more attention to the food.”

A question of texture

Besides taste, other senses are also convened. “During my trip to Japan,” Maya recalls, “I ate a lot of algae and visited nori farms. Japanese people surprised me, they love sticky food. In Western food culture, viscous foods are considered offputting, revolting. But these foods also evoke eroticism and sensuality. Algae give us pleasure, satisfaction and umami taste. Experiencing pleasure and joy changes us. That’s why, for my speculative cooking workshops, I always bring strange and queer ingredients so that the participants can transform them into meals. And algae are undoubtably queer!”

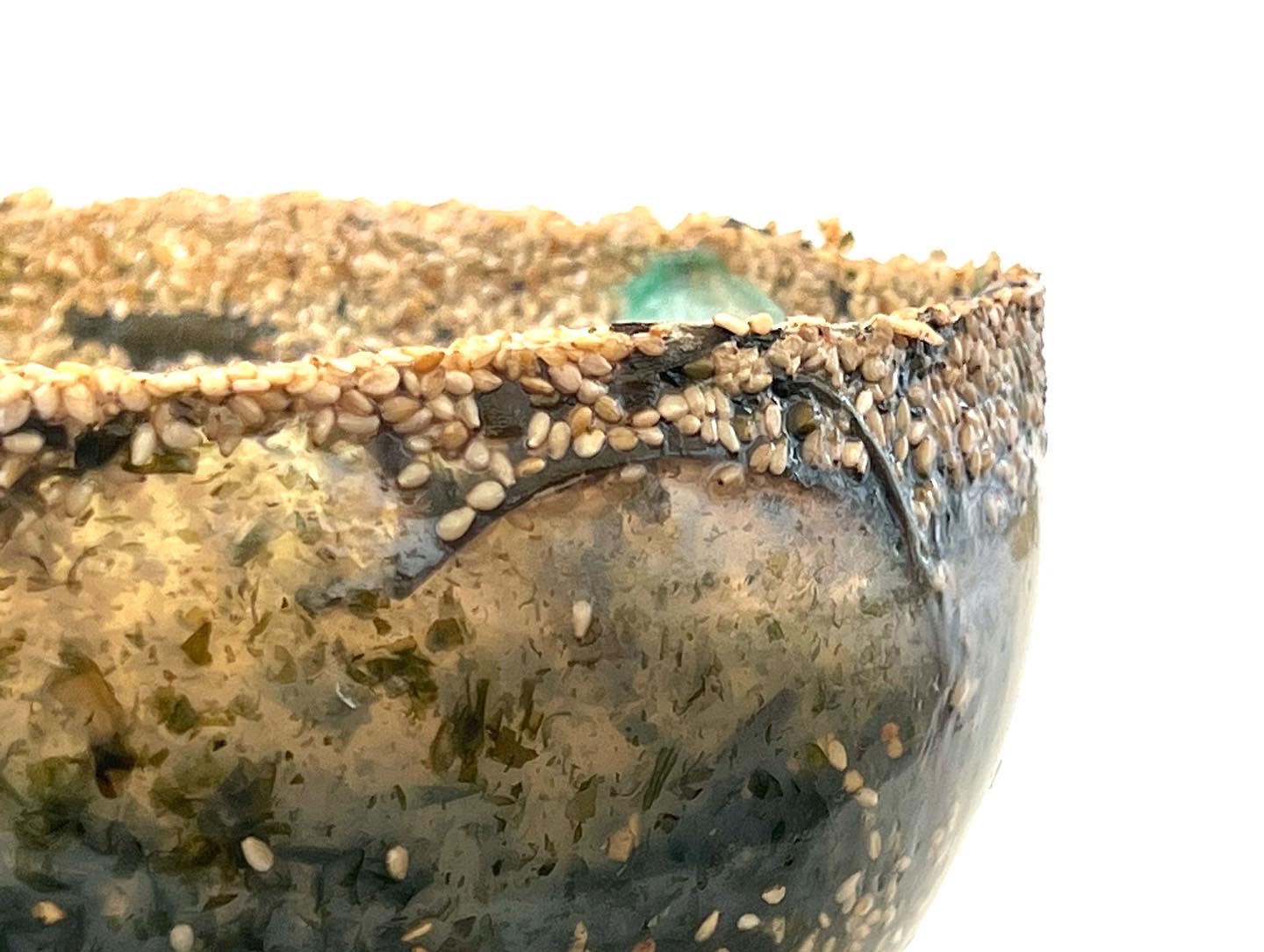

This research on texture is also done in collaboration with the artist and textiles/materials designer Alexia Venot: “Maya and I started to think about performative dinners, where there would be no distinction between the food and the plates. This raises a question that is common to both of our practices and that was also raised by Donna Haraway – the act of becoming one with the material and digesting our own work, putting into practice the compostability of the world, thinking about the life cycle of objects and also of projects. We work with a creative research approach. We share the same materials. Living together in the same space and working together creates a kind of alchemy, so that her recipes, and the materials that I create, act together.”

Banquet participants not only tasted the food presented on plates made by Alexia for the occasion, they ate the dishes too. “The materials are bioplastics, biopolymers made from algae and binding elements such as algae or sesame. The result is gelatinous. This also involves research over time, as the materials evolve as they dry; they harden, shrink, change color.”

Alexia mixes, presses and cuts, she uses molds, sometimes creates optical illusions, where temperature and humidity are especially important to the creation and durability of the dishes. This process has led her to question her own relationship with matter: “Our conventional way of transforming materials is really violent, it tells us a lot about our relationship with technique. Here it’s about finding a new sensuality by doing things in ways that are more care-based. When Maya works with kombucha, she has an affectionate relationship with it, she lives with the material and it’s part of her everyday life. In our approach, there is less determinism in the materials. My background is in art/sciences with research methods that come from engineering. I became interested in cooking also because in certain aspects, it requires less precision. There’s a magic side to cooking, with lots of intuition that comes into play, but also transmission, things that we’ve learned. There is gestural memory. It’s interesting to think about design in terms of cooking, rather than as an experimental laboratory.”

A question of relationships

Maya sees cooking as a cultural act, but also as a revealer of relationships: “I don’t do synthetic biology, but I would qualify myself as a biohacker because we have always been biohackers, in the sense that we have always transformed matter and modified it. We have always selected plants and animals. We have always interfered in our environments and modified them. The cooking process was no doubt the first chemical process. We know that the human brain was modified by the introduction of fire and facilitated access to proteins.”

Working with algae also means considering the local environment: “Food culture is huge in Korea, and lots of preparation processes still reference harvesting or aquaculture, a connection to the maritime world and the oceans. In Roscoff, I collected seaweed, I bathed in a forest of kelp. I tried to incorporate this carnal knowledge into my work. I’m very much influenced by the concept of eco-sexuality developed by Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens. By bathing in these kelp forests, you perceive a different world. You absorb the movement of seaweed in the water. You touch their sticky surfaces. It’s an impression that stays with you and inspires how you’ll cook them afterward.”

This process also extends to Alexia’s creations: “We experimented with these techniques for the first time at dinner in Bourges. Once we had finished eating, we decided to bury the dishes. It’s quite pleasant to bury your own objects after use, we nourish the humus and go away unencumbered. It’s in-situ, neither discarding nor recycling, you’re feeding the soil.”

A question of forms

GOFE is also the “media kitchen”, speculative cooking commissioned by Maya Minder and conceived with Victor Yvin & Pacôme Gérard Designers Artisans, Gabriel Violleau from the agency Bientôt architectes urbanistes and Ewen Chardronnet from Makery during their “Homo Photosyntheticus” residence at Antre Peaux’s UrsuLab in Bourges. Maya explains: “The idea was to create cooking that can be activated. We made racks to display the tools of speculative cooking, as well as algae and various other objects. Even the table is like a topographical landscape, non-uniform, that tells a story.” The installation is activated during workshops, performances and cooking presentations, inviting other artists and the general public to develop their own stories through cooking.

Victor Yvin comments on the design process: “For these creations, we worked on the entire process, from harvesting the algae to ingesting them. That was why we designed a table that we could work on directly using tools.” Pacôme Gérard adds: “We were inspired by certain medieval tables that were both a recipient, with plates dug right into the surface of the table, and a centerpiece of the room, a piece of furniture whose role changes during the course of the day. We tried to create forms that stimulate the imagination and invoke as many uses as possible, to use it freely. This table is made to be transformed little by little.”

In order to obtain these unique forms, the woodworking designers used a digital milling machine. Victor Yvin explains the process: “The machining is controlled by computer. We have a 3D model and processes for preparing the wood. We work layer by layer. We gradually remove material until we reach the final form. We smooth out the curves as much as possible, then there is a lot of sanding down, and finally the object is finished using carpentry tools.” Pacôme Gérard adds: “This technique lets us access a formal repertory that is a much longer process when done by hand, especially with wood that is hard like oak. We wouldn’t know how to access that repertory otherwise.”

These cooking utensils invented ad hoc are also an invitation to rethink our usual habits. “Each food culture has a different way of processing and cooking foods,” observes Maya. “Even the way we cut vegetables, cook meat, are skills that we received from our parents, as if we are cooking from memory. These tools are, once again, a departure toward a speculative, futuristic, post-modern lifestyle.”

While some utensils resemble conventional cooking tools, others invite us to discover new practices, just as some extend our own limbs. “We are seeking an ancestral futurism, a fusion reflected by the installation,” Maya continues. Here, the utensils may seem out of proportion with our habitual cooking tools, adapting to the length of macroalgae, which can reach several meters.

“With these utensils we imagined new gestures to pick up the seaweed, crush them, cut them, prepare them like microalgae such as spirulina,” Pacôme Gérard explains. “For example, we have one tool in the shape of a DNA strand to mix, homogenify the algae.”

The table was also designed like a living object. “This is where animism appears,” says Maya. “The table will evolve, especially in its appearance. I am careful about staining it, but it’s an artwork that is also functional. It will be touched and it wants to be touched. There is a form of sensuality. It will carry the marks of its history.” Victor Yvin adds: “We used oak, which is a wood that reacts strongly to tannins and humidity, and therefore to work with algae. It’s a canvas that will be transformed. Now it’s blank because we haven’t used it yet, but we thought of it like a kind of painting where running water would be painted across it. The idea was to favor these traces, which resonates with Maya’s work as she recycles the tablecloths used for these banquets.” Tablecloths that frame the installation presented at Cité Internationale des Arts.

Green Open Food Evolution was part of the “More Than Living” group exhibition during the Open Source Body festival at Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, and will be presented at Rencontres Mondes Multiples by Antre Peaux in Bourges, France, from November 19 to December 4, 2022.