Devastation becomes a Continuum that can be Gamed, a review of the 2020 Transmediale Symposium

Published 7 February 2020 by Rob La Frenais

The 2020 edition of Transmediale was on the subject of ‘networks’ and was the outgoing edition of Festival Director Kristoffer Gansing, to be succeeded by Nora O’ Murchú from Ireland. Rob La Frenais followed the ‘End to End’ symposium for Makery.

Berlin, special report

The Berlin of Poitras and Snowden has always been the battleground for the great struggles of freedom of information and the standoff between activists and the great media corporations, Facebook, Google and Amazon, and this symposium was no exception. In the closing hours of the conference, one felt a great despair at the last gasp of any sense of net neutrality and an unwinnable conflict similar to the battle to turn the world around to prevent global heating; the struggle between the lonely ‘network aware’ activists and the behemoths of social media. I was able to attend the main stage events, but as always at Transmediale, the timings prevented me from covering the parallel events.

End to End

The ‘End to End’ symposium started promisingly with ‘The Where and Whens of Networks’ and some great energy with a rousing call to challenge the idea that the internet exists outside time and space. Moderated excellently by Diana McCarty of Berlin’s Reboot FM, scholar Michelle M. Wright introduced the historical narratives of the ‘middle passage’ – the colonial routes of slavery. She used these to illustrate her notion of time and space being an essential element to understand history. Most of us have the idea, generated by the classic ‘Roots’ narrative, that there was a precolonial time when black people lived in Africa, colonialism came and the slaves were kidnapped and brought to North America, then liberated, segregated until the ‘60s and now we have a post-colonial present. According to the studies of blackness by Wright the picture is far more complex, with slaves and former slaves living in Europe, the Caribbean and other places.

There is also the complicated role of Germany and black Germans from its colonial period. She brought us also the the Second World War, which not only involved black men fighting but also black women both on the home front and as ‘computers’ and other support roles. So the histories of colonialism and slavery become a fundamental network in time and space. Diana McCarty also reminded us of different routes in time and space by mentioning the links between Detroit and Berlin, first with the Kraftwerk connection and the Detroit-Berlin One Circle Festival last year.

Felipe Fonseca, from OpenDoTT in Brasil (read him in Makery), provided some useful comments. It was naive to think that networks could provide meaning where meaning is lost. What were more important were social bonds – pre-technology networks not only based on affinity – music etc. – but empathy. Using networks to bypass industrialisation one might build some sort of ‘hopeful time machine’ and reboot the system. He couldn’t imagine even a small village where there is no data collection. So who owns the data? Right now, of course, a lot of grassroots development by labs in rural settings is overshadowed by the larger oppression taking place in that country.

Ulises Ali Meijas introduced the term ‘Paranodal’ , where anti-colonialisation reclaims space and time. Rejecting a world in which data extraction and collection is automatic, he emphasised – as many other speakers would later – that network idealism is dead. He created an amusing analogy with Google’s terms of service, which we agree to whenever we install Google Chrome, to a historical statement – read in Spanish, which none of the speakers could understand by the conquistadors in the 15th century to the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas. Essentially it reads: “Submit to us or we will destroy your villages and kill you all” . In the present world of cheap nature, cheap labour and cheap data, he compares the trinkets brought by the Spanish to exchange for gold to dogface apps on social media being used for extractive data.

Empires and Ecologies of the Cloud

Where does the internet live? In ‘Empires and Ecologies of the Cloud’ Mel Hogan introduced some interesting facts about how data infrastructures also cause climate change. She has done considerable research attempting to enter the secretive world of server farms and data centres. It’s difficult to get a measurement of emissions from these places but apparently a few Google searches are enough to cook an egg. In other words, data was the new oil. To power a medium sized server farm you’d need to have a million cyclists at 100 watts an hour. Apparently only a very small percentage of server farms use renewable energy.

Interested in the emissions caused by people attending conferences such as this, I asked her about the comparative emissions between, say train travel and a conference call involving 30 people. She felt it was an interesting point but the emissions figures from the server farms and data centres worldwide are a closely-guarded secret. Although I arrived by train, this still produces emissions. I wonder if by walking or cycling from Toulouse to Berlin, I would produce as many emissions as a Zoom call to attend Transmediale. In the discussion that followed, Teresa Dillon called for a fightback, “We shall do all the mischief and disruption we can”. But how? There are internet protocols to resist disruption. Can we attack data centres? No. But movements like the one to actively stop deportations from the UK could be a starting point. Finally, Bernard Stiegler introduced the main issue of how to reverse the paradigm of eternal growth which is leading us to a climate disaster, introducing what he called the ‘deproblematisation of work’. Why are we all being forced to work when less work, less growth is what the planet needs? He directly links decarbonisation with what he called ‘deproletisation’.

The lecture performance ‘Next To Devastation’ by Matthew Fuller and Olga Goriunova raised the problem of ‘the end’, pointing out that the catastrophe started with Columbus and ending with what they called today a ‘parching of the virtual’. They cited the wildlife now thriving in the closed zone of Chernobyl which was diverse but still to this day exhibiting mutation. They felt the current irresolvability – a structural incapacity to sort out the problem of climate damage started in the Cold War with the general economy of deterrence which produces what they called a ‘generalised sludginess’ similar to the game of the ‘prisoner’s dilemma’. In fact they proposed that the answers could indeed come from game theory, navigating the ecological crisis with “transversal forms of thinking, doing and bleak joys” (following their book title). Devastation becomes a continuum that can be gamed. In response Luiza Prado de O. Martins introduced the worldview of indigenous shamans with their ideas to postpone the end of the world, literally raising their arms in their dreams to hold up the sky together. She cited a recent event in Sao Paulo where the sky literally fell in the street with ash from the burning rainforests being blown to the city by strong winds. Finally Nelly Y. Pinkrah reminded us that the planet will eventually heal even though it may destroy us humans first.

Deplatformatisation

In ‘Deplatformatisation and the Ethics of Exclusion’ Eva Haifa Giraud talked compost. Another network, organic this time, involves entanglements of non-humans, such as slugs with their sticky lives. Humans also entangle in organic networks with different soil types though toilets and drainage. Citing the veteran climate activist Starhawk, she described the practical infrastructure of protest camps with borrowed shopping trolleys supporting and feeding protestors. Her food activism countered academic arguments against disrupting narratives about compost “Compost doesn’t come out of nowhere … infrastructures take collective responsibility for it”. She also cited critiques of veganism by Donna Haraway stating this sort of opting-out favoured individualistic politics as opposed to collective change. Quoting Jo Freeman’s ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness’ she stressed that pluralism can carry exclusion. I asked her whether this was reflected in last October’s Extinction Rebellion’s rogue group action where activists climbed on and stopped a tube train in London in a working class area where people were trying to reach low paid zero contract jobs? She agreed and was also critical of this.

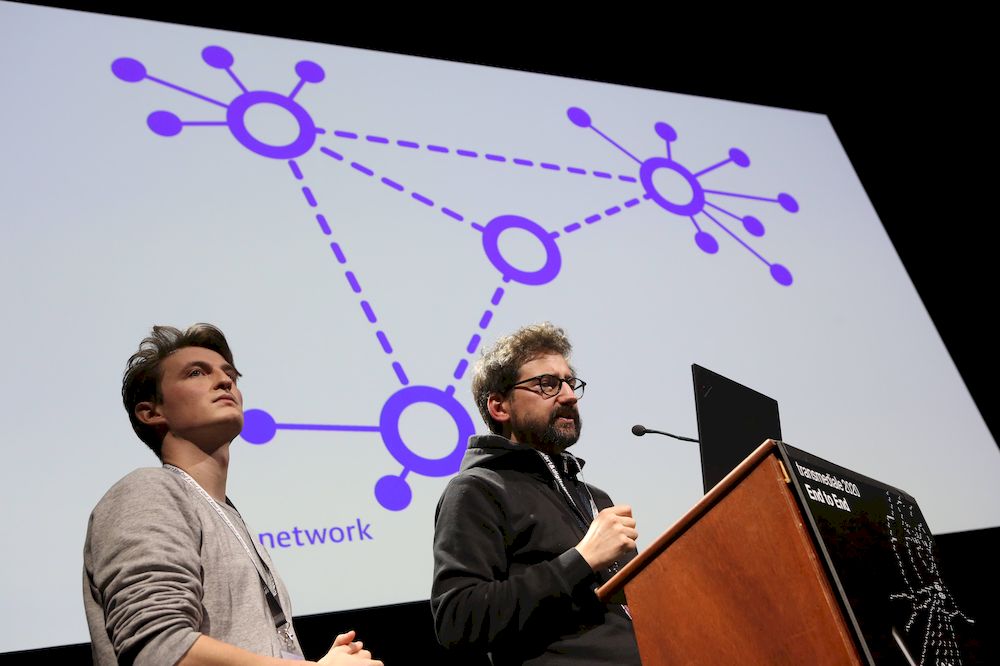

Now to alternatives to the social media behemoths. Roel Roscam Abbing and Aymeric Mansoux made a coherent presentation about the decentralised democratic social media cluster Fediverse. It has been set up with strong encryption and anyone can choose to use any of the ‘nodes’ specialising in different areas, from video sharing to sex work, such as Mastodon, Peertube and Funkwhale. Of course there are problems and the creators have had to act against online harassment and the Alt-right and trolls using it. In their words “Fediverse is open to everyone but not everyone is welcome”.

We Are Not Sick

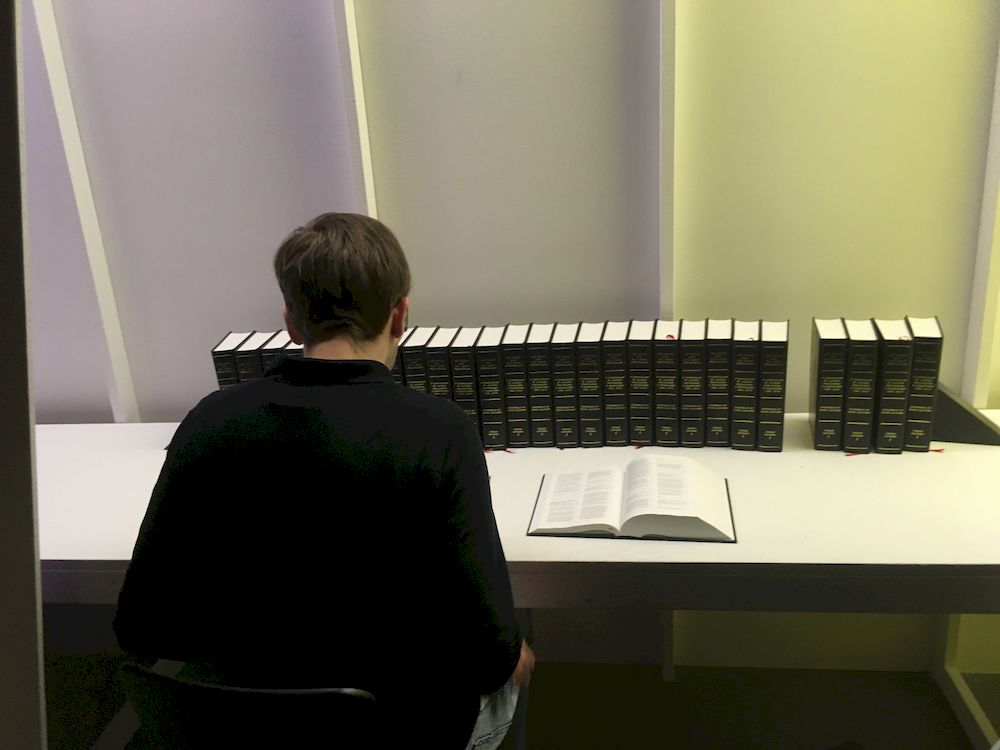

Central to the debate, and focussing our minds on the real problems facing how we connect was the almost religious sermon, or in their words ‘theory jocking’, We Are Not Sick’s (Geert Lovink and John Longwalker) ‘Sad By Design’. With a painfully bright searchlight circling the audience, there followed an orgy of on-platform nihilism and melancholy slogans like “Sorry I’m Dead” “Happy Depression everybody” and “Exhausted by the online world” and images such as a man weighed down in a Christ-like position with the Facebook logo resembling the cross and images of people snorting ‘likes’ like coke. So we can pretty much assume that Lovink and Longwalker want us to all leave Facebook and Twitter. In the discussion that followed, however, they made it clear they were not advocating ‘European offline romanticism’, notions of ‘real life’ and ‘real’ communities. In fact scientists and psychologists employed by social media giants have actually factored in this very impulse. So what to do? They advocate using Fediverse, but something more radical may. be needed to “open up and speak about the addiction, the mental mess – many people hate their apps but can’t delete them”. Again it was suggested we adopt climate activist strategies and blockade the data centres and server farms. To some extent the background of all this is the large history of the alternative net cultures of the post 1989 era in the‘90s, which was heavily represented in the Transmediale exhibition ‘The Eternal Network’. This was taken almost to a ludicrous extreme in David Gaulthier’s ‘Revision: List Server Busy. Full Digest Rescheduled’ which turned the entire archive of the lists Nettime, Crumb, Empire, Spectre and Syndicate into painstakingly-bound hard copy books with tiny print to be read with a microscopic lens.

In ‘Neural Network Culture’ Stephanie Dick described the days when people, often women, were pre-machine ‘computers’. In early development of AI “people were once the measure of the machine” mapping human intelligence with machines designed to be like chess-players and mathematicians. Scientist Hao Wang challenged this approach and stated machines should be more like workers and be unimaginative plodders processing data at higher and higher speeds. But this approach meant machine learning of big data inherits social bias, where data sets are processed by parameters we set.

I thought of this history when watching Bahar Noorizadeh’s ‘After Scarcity’ in the otherwise rather thin and 90’s dominated exhibition, ‘The Eternal Network’.This excellent sci-fi video essay tracks the Soviet Union’s attempts to build a fully automated command economy. The gigantic centralised industrial and agricultural was controlled simply by human ‘computers’ – bureaucrats who at one point amounted to a quarter of the entire workforce. After the death of Stalin, some Soviet scientists realised that cybernetics was not a bourgeois pseudo-science as previously considered, but could in fact be used to efficiently control supply and demand of goods in the absence of a market economy. This film effectively used a mixture of data representations and slogans take us through the history of this failed project (the bureaucrats realised they would be out of a job). Meanwhile in the decadent west ARPANET was developing in an unusual collaboration between science and the military and we all know the rest of the story.

Bahar Noorizadeh, ‘After Scarcity’ (Trailer):

Katharine Jarmul described her strategies of ‘adversarial hacking’ on surveillance capitalism in which visual recognition images of a turtle might become reclassified as a rifle, for example. What if everyone gave, for example the same address “arsloch.de’ for those irritating internet access forms we all have to fill in for public wifi? Or all wear the same wig and coat the same day for the face recognition cameras? She calls on us humans to do our best to “poison’ the AI systems” in our everyday lives. Meanwhile Tega Brain described AI-controlled drone killers being used to fight mosquitos and concluded that the indeterminacy of relationships between natural systems cannot be predicted by machine learning.

In the final debate incoming Director Nora O’Murchú laid out her stall. Future Transmediales would reflect collective concern about climate disaster, initiate collective action and tackle this with new physical infrastructures towards networks. Reflecting that the backdrop for this Transmediale was Brexit day – a number of us gathered at the Brandenburg Gate at midnight to sing a defiant chorus of ‘Ode to Joy”- she emphasised the concerns from Ireland about the retaking of control by the UK, and stated that EU withdrawal directly undermines the peace process.

Internet as hyperobject

Jussi Parikka, underlined further the unfolding from net discourses of the 90s emphasising the ‘when’s and where’s’ of the network, mentioning past networks like the canals and telegraphs of the 19th century. He proposes a world epistemology of networks and a nuanced understanding networks across sexualities and species, saying that network neutrality has a decolonial history.It was not about how it works but how it has broken down. In complex forms of activism how do we be radically public?

Rosa Menkman likened her data self to being a single node on a mountain in a snowstorm, citing Borges’ commentary on Dostoyevki’s character ‘The Idiot’, who saw things in infinite scales of reference, more than super-resolution. We needed compromise to see anything, a lens, filter, bias, aberration – impossible to say anything. We needed to discriminate but be aware of the biases and train ourselves to think through vectors. During her 2 month residency at CERN she learned to “jump through the skills and become a super-user of the networks”. She concluded there was too much data, too many parameters. Knowledge was fluid.

Outgoing director Gansing stated there was no ‘thing’ that is a network. The nearest thing was Timothy Morton’s ‘hyperobject’. We were living next to devastation and change, raw data in itself did not exist. There was a secrecy of knowledge about climate damage which has to be exposed. Geraldine Juárez ended with the statement that “Histories of resistance are there. The powers that run the infrastructures are beating us up.” An audience member asked in response: “Can we look at the future in how Transmediale can serve the public like the Chaos Congress, such as practical workshops to help us through the difficult times that are coming?” Thus has the future of Transmediale been laid out. I felt this form of ‘net discourse’ has finally played itself out.

The symposium now held in the imposing Volksbühne, I missed the sprawling, chaotic nature of the way this festival used to spread itself out in the sixties brutalist labyrinth of the Haus de Kulturen De Welt, attracting Berliners and visitors alike. This time you needed a lanyard and wristband to get into the building, which discouraged the community aspect of Transmediale, once a social focus at this time of year for Berlin. The HKW, by contrast, when I visited the exhibition, seemed sad and empty. Maybe time has run out for the ever-nomadic lives of black-clad netizens who regularly flocked here.

More on Transmediale 2020.