Smart Cities Asia: Will tomorrow’s smart city be a sustainable one?

Published 14 October 2017 by Cherise Fong

Should the smart city be the sandbox of the Internet of Things? The Smart Cities Asia conference, held in Kuala Lumpur on October 2-3, explored various manifestations of high-tech urbanism.

Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), special report

The Kuala Lumpur Convention Center (KLCC) is situated in downtown Kuala Lumpur, at the foot of the iconic Petronas Towers, connected to a vast shopping mall that segues directly into the metro, at the edge of an elegant park criss-crossed by jogging paths, playgrounds and landscaped fountains, all surrounded by busy traffic roads. Inside, high security and air-conditioning full blast. A typically contrasted venue for a symposium on the city of the future.

It was no coincidence that the 3rd edition of Smart Cities shared the stage of the convention center with the 1st edition of Next Big Tech, the main event of Big Data Week in Kuala Lumpur this October 2017. While the technologists advanced that more than 60% of people make decisions based on experience and instinct rather than data, some urbanists have claimed that they “are drowning in data but starved for wisdom”. After acknowledging the trend of ever more tech-savvy cities, the opening session of Smart Cities Asia reiterated the obvious: technology is just the tool, the goal is a sustainable city in the best interest of its citizens.

Likewise, not all speakers came to preach big data. In particular, Professor Soo Hong Noh recounted the case study of the restoration of the Cheonggyecheon river in Seoul, South Korea, spurred by his personal initiative into concrete action by former mayor Lee Myung-bak. Since 2005, this downtown waterway has become a green destination for recreation and culture, attracting some 233 million visitors. Among other positive consequences: increased number of species living in the area, significant calming of motor traffic, improved public transport, higher valued real estate and even cooler temperatures.

Fourth industrial revolution

Jong-Sung Hwang, researcher in smart city solutions for the South Korean government, offered a brief history of the smart city: the first generation was born when the Internet was integrated into the city of Amsterdam in 1994; the second generation was characterized by the massive use of IoT (Internet of Things) and engendered the ubiquitous city, as seen in the experimental city of Songdo in Incheon since 2004. The third generation incorporates big data (especially for predicting traffic flow), and the up-and-coming fourth generation integrates artificial intelligence (beginning with autonomous vehicles). The question is, will this much-hyped fourth industrial revolution be sustainable?

Open data and citizen participation are among the core issues of the smart city. Hwang cites the example of South Korea’s most used mobile application: a public transport app that uses open city data, developed by a high school student a decade ago. In Helsinki, the Finnish capital that first put its data online in 2005, home of Nokia and Angry Birds, data is no less than the operating system of the city, according to research urbanist Roope Ritvos. His many pilot projects include Smart Kalasatama, where autonomous electric buses have been running through the neighborhood in real traffic since 2016, the harmonized network of CitySDK APIs for European cities and research institutions, and Select For Cities, a competition to develop an Internet of Everything (IoE) platform for the cities of Helsinki, Antwerp and Copenhagen.

Presentation of “Smart Region Helsinki”:

Urban technologist Saibal Das Chowdhury demonstrated Urbanetic, a 3D visualization platform that integrates contextual city data with dynamic links that immediately show the impact of different variables. Like an ultra realistic Sim City of big data, Urbanetic lets people compare cities and share solutions to common problems. Its collaborative approach to urban planning also includes an online voting system where citizens can select their preferred model before it is passed on to developers.

Demo of Urbanetic based on a rendering of Melbourne, Australia:

Cities are at the heart of the future sustainability of our entire planet. Pichaya Limpivest of Intel Asia, co-organizer of the conference with the Malaysian Knowledge Group, reminds us that by 2024, 58% of the world’s population will be living in cities—and that cities consume 75% of our planet’s energy. Knowing that 90% of Cloud technologies run on Intel chips, it’s enough to send a shiver down our spine, imagining the spectacular apocalypse of our digital universe just a few decades after Y2K.

Aquarium hack

Meanwhile, the organizers had the good idea of debating on stage the pros and cons of IoT on the scale of a city: in proposition, Maksim Pecherskiy, Chief Data Officer of the City of San Diego, USA; in opposition, Vladimir Bataev, smart cities expert at Zaz Ventures in the Netherlands. While the Californian clearly stressed the advantages of ubiquitous sensors and real-time data feedback to optimize the general operation flow of the city, his evangelism was overwhelmed by his opponent’s merciless counter-arguments.

As the devil’s advocate, Vladimir cited numerous examples of abuse of power and trust, from the television in 1984 that is always watching us to the North American casino that was reportedly hacked through its fish tank…not to mention the threats to individual privacy, the exorbitant costs in energy and rare minerals, the fuzzy concept of ownership (when the consumer owns the hardware but the corporation owns the software)…before concluding that “A society that sacrifices liberty for security does not deserve both.” Just as an airplane is a computer with wings and a car will soon be a computer on wheels, he warns, “We are essentially creating a weapon that can be used against us.” And unlike in the world of Facebook, where you can simply delete your account if you don’t want to play anymore, it’s a bit more complicated to extract yourself from the urban infrastructure. Finally, he advocates both technological and human responsibility in innovation, especially when it involves an entire metropolis.

Self-sufficiency through the blockchain?

The next day started off more optimistically with a talk by Ruben Tan, cofounder and CTO of the Malaysian start-up Neuroware, who defended the particularly secure and potentially revolutionary technology of the blockchain. This distributed and decentralized network, secured by a historical method of consensus, is what he believes to be the ideal base for micro-grids as the framework for peer-to-peer commerce. Prototypes of solar power markets are already being experimented in California and New York in the United States.

As an open, neutral and collaborative platform, the blockchain would also facilitate the automation of what happens behind the scenes of a smart city, for example when a smart refrigerator orders a new carton of milk every three days, which is delivered to your home by a drone, while the milk producer is paid automatically. Well beyond the killer app of bitcoin, this micro-grid could also operate as a self-sufficient community in time of disaster. Ruben affirms that the blockchain itself has never been compromised since its launch in 2009. The only risk he recognizes is potential centralization by certain majority miners.

Playing with transportation

Optimized traffic flow, autonomous cars…urban mobility remains at the heart of the smart city. In terms of traffic jams, Kuala Lumpur is better off than Manilla but worse off than Jakarta, according to Edward Ling, the charismatic Malaysian who came to talk about Waze, the community road navigation mobile app that was acquired by Google for 1 billion dollars in 2014. With 5.4 million active users, Waze depends on the contribution of active drivers to signal obstacles on the roads, as it tracks each ride in real-time in order to always suggest the best route based on this crowdsourced data.

In the U.S., says Edward, 63% of people who call the emergency number 911 on the road don’t know their location, while 70% of road accidents are reported in Waze before 911 is called. As a result, the response time of emergency services was reduced by 4 minutes. Drivers should save an average of 5 minutes per day, while the average driver spends 4.3 of her life driving… Of course, as autonomous cars become more widespread, he admits that the next generation may never need to drive. But in the meantime, doesn’t facilitating the flow of automobile traffic boil down to encouraging peopole to drive their cars?

In Singapore, twentysomething Abhilash Murthy developed a chatbot on Facebook Messenger that helps people get around the city by bus—and most importantly, how long they need to wait for the next one—thanks to the local transportation system’s open data. Since its launch in October 2016, Bus Uncle has gained more than 20,000 users who chat naturally with him… in Singlish. For Bus Uncle communicates exclusively in Singaporean English, whose avuncular reactions range from sarcastic to reassuring, telling jokes and evolving through conversations with his fans. Hopefully he will also have a positive influence on the implementation of Singapore’s first electric buses!

If motor vehicles are responsible for 60%-70% of urban CO2 emissions, according to Iván Páez Mora, founder of Kappo Bike, the Chilean evangelist of urban cycling understands very well that the upward trend of driving cars in the city is not at all sustainable: “Changing the way we move is fundamental to the well-being of our world, the feasibility of our way of life and to avoid an imminent world collapse.”

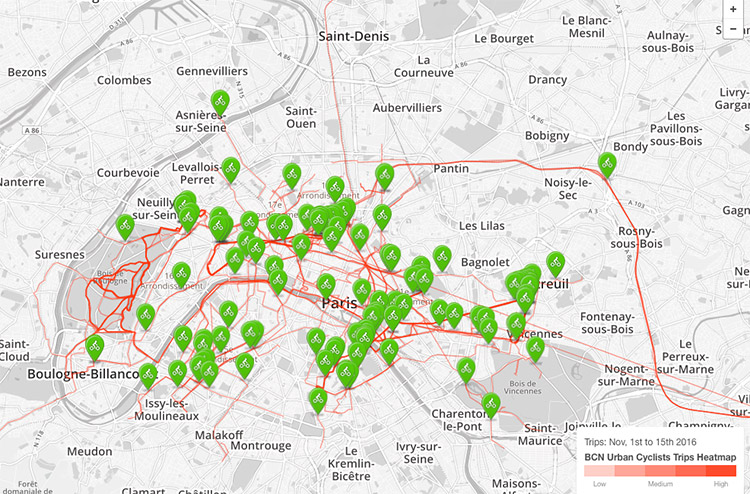

His mobile application aspires to be both the Pokémon Go and the Waze of urban cycling (also looking toward an upcoming wave of e-bikes). But without augmented reality or an integrated map, its main asset consists of tracking the movements of cycling “players” and sending this data to municipal governments so that they can better improve the urban cycling infrastructure. The number one obstacle to cycling as a general means of transportation is the lack of safe and convenient infrastructure.

Launched in 2014, the Kappo app now claims some 50,000 active users in 50 countries. While waiting to analyze the real-time world map of live cycling routes, we can visualize the data of Kappo’s nine top cities on its online heatmaps.

Bringing pro-cycling initiatives back to the homefront, Penang City Council mayor Maimunah Mohd Sharif tells a wider audience how she installed 179km of bike paths around Penang, from the airport to the island. This dedicated infrastructure complements Southeast Asia’s first bike-sharing system, Link Bike in George Town, Malaysia’s second most populous city, whose historical center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. She proudly affirms that 47% of Penang residents consider themselves “very happy”, in stark contrast to the 49% who say they are “very stressed” in Kuala Lumpur. For the Penang mayor, we need to “learn globally, apply locally”.

Outside, the air is hot and humid, the streets of Kuala Lumpur are noisy, crowded with vehicle traffic and polluted with exhaust fumes. While I consider myself a motivated cyclist, I am less inclined to hop on one of the inexpensive public oBikes, which I see parked (but rarely in use) in various spots downtown. However, I was lucky to stumble upon an informal meetup of cyclists by night at the Jamek mosque.

On the way back to the airport, Rohana, my taxi driver, tells me that today all taxis, as well as some buses and trucks, in Kuala Lumpur are natural gas vehicles, which use much cheaper fuel, although it costs 6,000 ringgits ($1,450) to convert the vehicle. She admits to having lost about half of her clients to Uber and Grab (which I also used several times during my stay), despite the existence of a local app dedicated to Malaysian taxis. Yet she remains true to her profession and determined to continue driving her taxi: “When everything becomes robotics, what are we going to do?”