Platform cooperativism: an alternative to uberisation

Published 30 November 2016 by Ewen Chardronnet

How does one relocate the governance of the digital economy? Trebor Scholz, Nathan Schneider and a crowd of engaged authors are listing alternatives in a publication on “platform cooperativism”. Makery selected the good papers for you.

Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider met at the OuiShareFest in Paris in 2014. They noticed they shared views on platform cooperativism as an alternative to uberization, or more precisely “platform capitalism” as the political specialist Nick Srnicek defined it. The project of a book emerged from this meeting, as a means to disseminate the scattered ideas of an international movement. Its website Platformcoop has since been relaying its initiatives. The book will be released this month to also support a reflection group, the PCC (Platform Cooperativism Consortium), officially launched on November 11 in the New School of New York (where Trebor Scholz teaches).

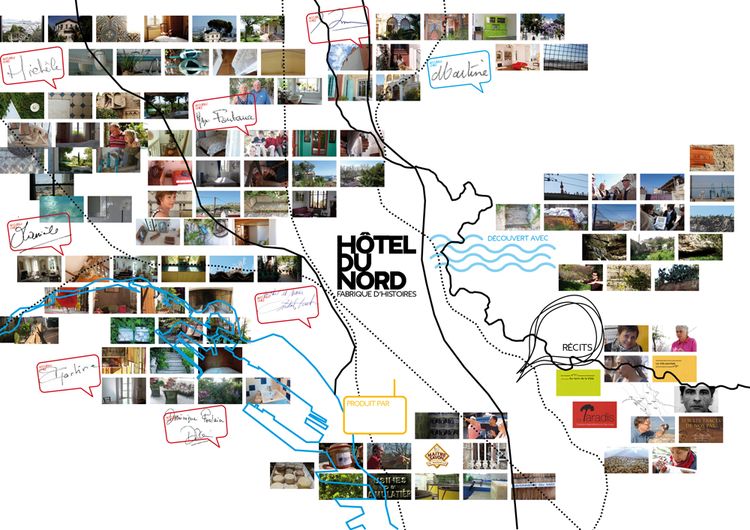

The ideas of platform cooperativism can be found for example in the British labor leader Jeremy Corbyn’s program “digital democracy”, or in the municipal policy of the Mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau, from the movement ‘Barcelona in common’. In France, the cooperative of residents Hôtel du Nord in Marseille wants to offer an alternative to Airbnb, organized by those who live, work and reside in the city. In Paris, La Louve offers the first cooperative supermarket of the capital. The future, say Scholz and Schneider, would therefore look towards cooperatives and the construction of alternatives against the breakdown of local social and solidarity economies brought about by the giants of e-commerce such as Uber, Airbnb, Deliveroo, Booking, etc.

Released by the alternative publisher OR Books (that functions by on demand printing), their book Ours to Hack and to Own, The Rise of Platform Cooperativism, a new Vision for the Future of Work and a fairer Internet offers a global panorama of these types of alternatives. One can find contributions from authors such as McKenzie Wark, author of A Hacker Manifesto, Saskia Sassen, the sociologist of globalized cities, Michel Bauwens, the promoter of P2P (peer to peer), or still Francesca Bria, the digital adviser to Ada Colau in Barcelona and coordinator of the recent initiative D-Cent of direct democracy and promotion of digital social currencies. To name but a few…

An inventory of initiatives by the Platform Cooperativism website:

What do they tell us in this book? That unlike the rules of the main algorithmic portals, platform cooperativism puts the online economic infrastructure in the hands of the people who depend on it the most. And that the ongoing experiences prove that a global ecosystem of cooperatives can be opposed to the concentration of wealth and the insecurity of workers created by the economy of the Silicon Valley. And ultimately, that Internet can be owned and ruled differently.

We selected extracts that illustrate this vision of a cooperative economy.

Trebor Scholz

“How platform cooperativism can unleash the network”

Pages 20 to 26

“The theory of platform cooperativism has two main tenets: communal ownership and democratic governance. It is bringing together 135 years of worker self-management, the roughly 170 years of the cooperative movement, and commons-based peer production with the compensated digital economy. The term ‘platform’ refers to places where we hang out, work, tinker, and generate value after we switch on our phones or computers. The ‘cooperativism’ part is about an ownership model for labor and logistics platforms or online marketplaces that replaces the likes of Uber with cooperatives, communities, cities, or inventive unions. These new structures embrace the technology to creatively reshape it, embed their values, and then operate it in support of local economies. Seriously, why does a village in Denmark or a town like Marfa in rural West Texas have to generate profits for some fifty people in Silicon Valley if they can create their own version of Airbnb? Instead of trying to be the next Silicon Valley, generating profits for the few, these cities could mandate the use of a cooperative platform, which could maximize use value for the community.”

(…)

“In opposition to the black-box systems of the Snowden-era Internet, these platforms need to distinguish themselves by making their data ows transparent. They need to show where the data about customers and workers are stored, to whom they are sold, and for what purpose. Work on platform co-ops needs to be co-determined. The people who are meant to populate the platform in the end must be involved in its design from the very beginning. They need to understand the parameters and patterns that govern their working environment. A protective legal framework is not only essential to guarantee the right to organize and the freedom of expression but it can help to guard against platform-based child labor, wage theft, arbitrary behavior, litigation, and excessive workplace surveillance along the lines of the ‘reputation systems’ of companies like Lyft and Uber that ‘deactivate’ drivers if their ratings fall below 4.5 stars. Crowd workers should have a right to know what they are working on instead of contributing to mysterious projects posted by anonymous consignors.”

“At its heart, platform cooperativism is not about any particular technology but the politics of lived acts of cooperation. Soon, we may no longer have to contend with websites and apps but, more and more, with 5G wireless services (more mobile work), protocols, and AI. We have to design for tomorrow’s labor market. In the absence of rigorous democratic debates, online labor behemoths are producing their version of the future of work right in front of us. We have to move quickly. Together with cities like Berlin, Barcelona, Paris, and Rio de Janeiro that have already pushed back against Uber and Airbnb, we ought to refine the discourse around “smart cities” and machine ownership. We need incubators, small experiments, step-by-step walkthroughs, best practices, and legal templates that online co-ops can use. Developers will script a WordPress for platform co-ops, a free-software labor platform that local developers can customize. Ultimately, platform cooperativism is not merely about countering destructive visions of the future, it is about the marriage of technology and cooperativism and what it can do for our children, our children’s children, and their children in the future.”

Nathan Schneider

“The meaning of words”

Pages 14 to 19

“In the area around Barcelona, among the thousands of members of the Catalan Integral Cooperative, I got a glimpse of what twenty-first-century cooperatives might look like. Rather than securing old-fashioned jobs, these independent workers help each other become less dependent on salaries, more able to rely on the housing, food, childcare, and computer code they hold in common. They trade with their own digital currency. In cases like this, the traditional lines between workers, producers, consumers, and depositors may become harder to draw.”

“This needs to change. Part of the cooperative legacy has played out in tech culture already. The Internet relies on free, open-source tools built through feats of peer-to-peer self-governance like, Wikipedia and Linux. Visit many tech offices, from a startup’s garage to the Googleplex, and there are self-organizing teams creating projects from the bottom up. Yet somehow this democracy doesn’t seem to make it to the boardroom; things are still pretty twentieth-century corporate in there, with whoever happens to own the most shares calling the shots. There’s a rewall. We can practice democracy everywhere, it seems, except where it really matters.”

(…)

“Governments should recognize that cooperative platforms will mean more wealth staying in their communities and serving their constituents. Rather than trying (and failing) to say ‘no’ to the likes of Uber, platform co-ops are something public institutions can say ‘yes’ to. We need laws that make it easier to form and finance co-ops, as well as public investment in business development—stuff that extractive businesses get all the time.”

McKenzie Wark

“Worse than capitalism”

Page 46

“The significance of platform cooperativism is that it is a movement that can place itself at the nexus of the interests and experiences of both workers and hackers. Why not use the specific skills hackers have to create the means of organizing information, but use it to create quite other ways of organizing labor? Cooperatives have a long history in the labor movement; indeed, in their origins, they looked back to forms of peasant self-organization of the commons.”

Arun Sundararajan

“Economic barriers and enablers of distributed ownership”

Pages 141 to 145

“In May 2015, I chatted with OuiShare’s co-founders Antonin Léonard and Benjamin Tincq during their OuiShare Fest, the annual gathering of over a thousand sharing-economy enthusiasts in Paris. I sensed a tension at the Fest between the purpose-driven and profit-driven participants: those who saw the sharing economy as a path to a more equitable and environmentally sensible world, and those who were excited by the massive infusions of venture capital into hundreds of burgeoning sharing-economy platforms.”

“Léonard spoke of the confusion and disappointment he detected from those who had hoped that the sharing economy would really change the world. ‘And because there was so much hope, the ones that were once so hopeful are now so disappointed, in a way,’ he said. ‘But maybe the problem is not so much how much money was invested, but why did we have this hope?’”

“Tincq, while agreeing with the perception of growing disenchantment, was focused on a simpler point: that the shift away from purpose and towards profit was driven primarily not by a change in philosophy but by a need for growth capital. In his view, at the time, for a nascent platform to bridge the early-stage gap and get to critical mass, there was no practical alternative to venture capital.”

(…)

“In light of these and other conversations, I find the excitement about platform cooperatives—especially in the form of sharing-economy platforms owned by their providers and funded through mechanisms other than institutional venture capital—both inspiring and contagious.”

Saskia Sassen

“Making apps for low-wage workers and their neighborhoods”

Page 154

“Neighborhoods are important spaces for low-wage workers. In the past they often enabled union organizing and the formation of mutual-assistance organizations. Much of this is lost today. There is work to be done to strengthen this neighborhood function. But this can only happen if the neighborhood is a space for connecting, collaborating, and mutually recognizing each other. Given the development of apps geared to low-wage workers, platform cooperativism could enable significant scale-ups in the deployment of such apps and in their spread. One key mode of scale-up would be shared ownership and shared governance. This would have the added effect of enabling collaboration among workers and among residents within and across neighborhoods, joining hundreds of years of the history of cooperatives with the digital economy. I see here beginnings of possibly new social histories.”

Francesca Bria

“Public policies for digital sovereignty”

Pages 223 to 227

“A very interesting example of a city that is putting forward alternative policies and forward-looking regulations is Barcelona. After the large mobilization of the 15M movement beginning in 2011, the anti-eviction housing activist Ada Colau, a leader in the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages (PAH), became the mayor of Barcelona, representing the main political opposition against the elite who brought Spain into a deep financial and social crisis, which left hundreds of thousands of families without a home.”

“The new coalition led by Colau has been crowdfunded and organized through an online collaborative platform that aggregates policy input from thousands of citizens. Soon after taking office, the coalition members embarked on a series of radical social reforms. In particular, they started to enforce regulations to block illegal tourism. The council froze new licenses for hotels and other tourist accommodations, promising to fine firms like Airbnb and Booking.com if they marketed apartments without being on the local tourism register. Barcelona then provided these companies the possibility to negotiate 80 percent of the penalty if they allow the Social Emergency Housing Consortium to allocate empty apartments to residents with subsidized rent for three years.”

“The city has called for a popular assembly for responsible tourism where citizens can discuss best practices and business models. The new government is also promoting new policies to foster a collaborative economy that generates social benefits locally. Besides these types of initiatives, Ada Colau has also promised a shift toward re-municipalization of infrastructure and public services. This is grounded in a very critical understanding of the neoliberal, surveillance-driven ‘smart city’ model being promoted by big tech corporations. The ambition, instead, is for a shift to a democratic, green, and commons-based digital city built from bottom up.”

(…)

“Cities, for instance, should be able to run distributed common data infrastructure on their own, with systems that ensure the security, privacy, and sovereignty of citizens’ data. Cities can then invite local companies, cooperatives, civil society organizations, and tech entrepreneurs to come in and offer innovative services on top of that infrastructure. One example is the European Commission’s CAPS program, which has invested around €60 million on collaborative and open platforms to pilot bottom-up, citizen-led projects with strong social impact such as the D-CENT project, developing distributed and privacy-aware tools for direct democracy and cryptocurrencies for economic empowerment. Initiatives like these can help ensure that the data produced by platforms, devices, sensors, and software doesn’t get locked down in corporate silos, but becomes available for the public good. Investing public resources for piloting innovative, cooperative platforms is necessary to enable credible alternatives to the current data paradigms exploited by the dominant platforms—integrating economy, technology, society, and policy, which would otherwise remain fragmented and lead to market concentration and regulatory breakdowns.”

“Ours to Hack and to Own”, Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider, ed. OR Books, November 2016, 272 pp.