How to (not) innovate with a coconut (2/2)

Published 26 July 2016 by Ewen Chardronnet

Marc Dusseiller, co-founder of the DIYbio network Hackteria, is a passionate promoter of open hardware. This is all the more evident in part 2 of our interview, where the activist scientist talks about the DIY microscope and the propaganda of innovation, which led him to create the Center for Alternative Coconut Research.

Marc Dusseiller (better known online as dusjagr) is a biohacking pioneer. After reflecting on the origins of the DIYbio movement in part 1 of this interview (done during Interactivos?’16 in Madrid), the ex-research professor in bio-nano interfaces at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich elaborates on the problems of open science and open hardware, as with the DIY microscope. Creating the Center for Alternative Coconut Research and the international Gosh! (Global Open Science Hardware) network were also acts of protest against the “Zeitgeist of innovation”, he explains.

Was it the open hardware movement, the rising popularity of 3D printing and Arduino that inspired you to promote the DIY microscope?

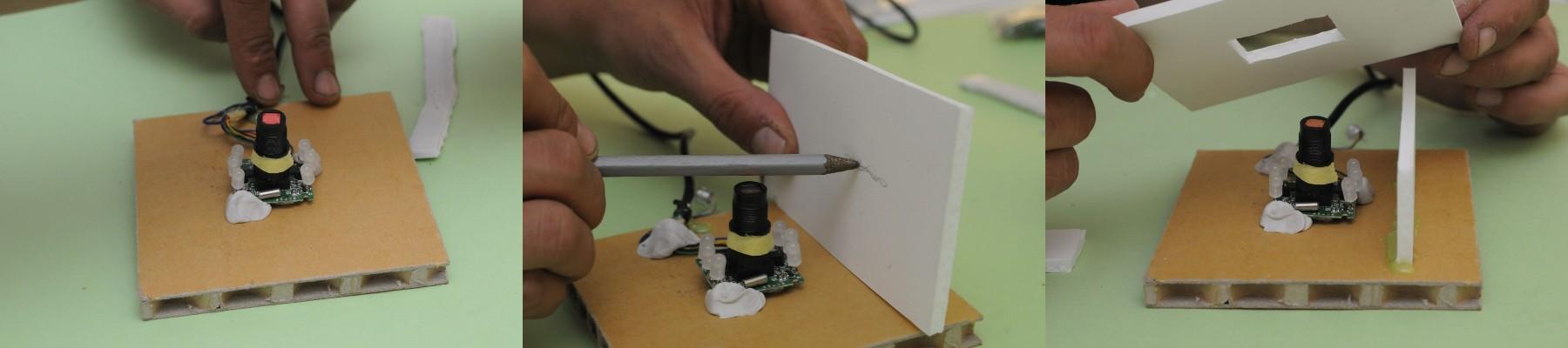

The microscope is really a very good project, where, with minimum knowledge in optics, hacking, and what to look at, you can do a lot of classroom biology with a 3-dollar device. It’s not the webcam that is open source—it’s a mass consumer electronics product that is repurposed for another (better) use. The open source is in the instructions on how to build it, but also in how to implement it in the classroom.

I experienced it personally as being extremely relevant in places like Indonesia, where even the best universities are not very well equipped. I remember when back in 2009, one of my DIY microscope workshops was picked up by a local individual collaborator, Akbar Nur Arofattulah, who then implemented the same workshop in hundreds of primary schools and universities, developing the design further. It was a massive multiplication of an idea. It is not so much because of the open hardware movement that now hundreds of schools use it in Yogyakarta, but because of a collaboration of individuals.

One stream of thought is the open hardware philosophy, but another one is that those DIY projects can also be low-cost, and it opened a new perspective into laboratory equipment, a new stream of work, focusing strongly on the demystification and educational aspect through the crafting of scientific equipment. The DIY microscope is a citizen science project, with artistic applications as well. But Hackteria being an underground network with a rudimentary wiki and not a university with big media power, the message on how to do this could not really reach the masses.

“Seni Gotong Royon: Hackterialab 2014, Yogyakarta”, documentary (trailer):

Many people don’t take an open source idea and implement it. I think this is because of the current celebration of innovation in our culture that make people think that when they do something it always has to be a novelty to be valuable. This Zeitgeist of innovation is opposed to my idea of open source. I’m interested in direct personal interactions, I don’t even think a website can do the job. People in China or France don’t Google in English, but in regular physical gatherings people are sharing, and hopefully will share it again. It’s nice if they give credit where the idea came from, but it’s not even needed. Even if they “steal” some ideas from the open source and market it, you know it is the Zeitgeist, and I don’t care about it so much.

Marc Dusseiller on workshops, DIYsect (2016):

Have you worked in the humanitarian NGO world? Because I see the potential of those tools for outreach in regions that lack medical facilities. What is your experience in these contexts?

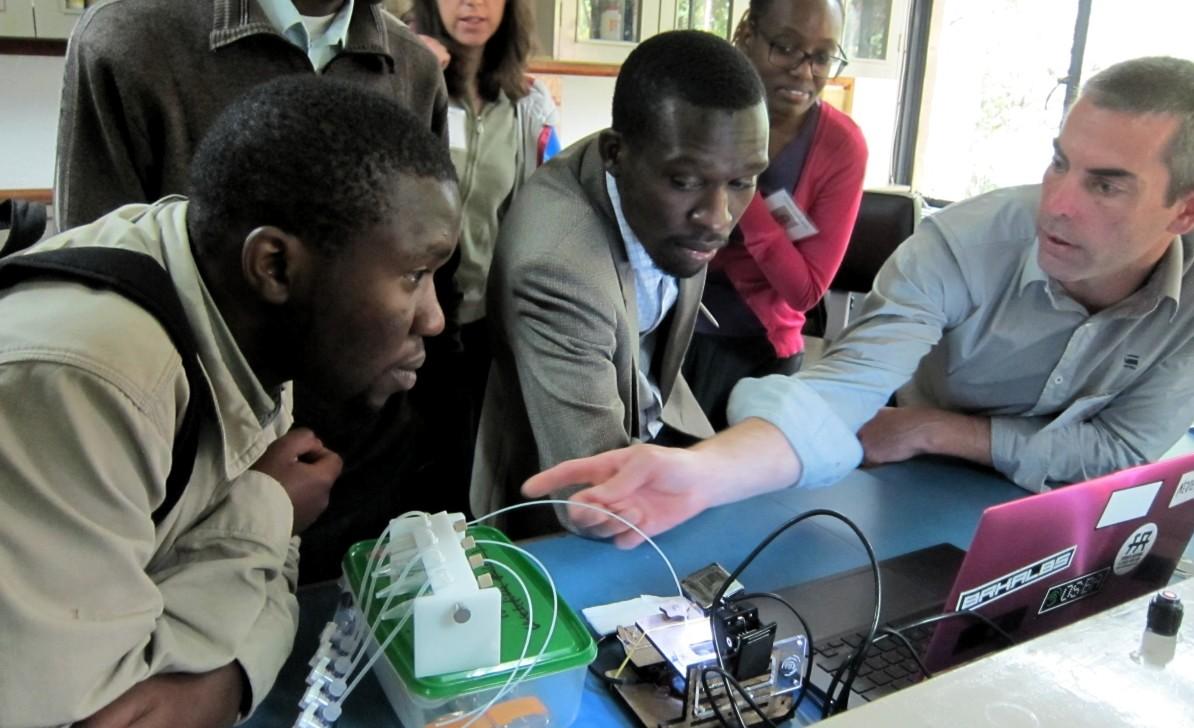

I’ve already worked in the biomedical field as a researcher, and I saw the potential to implement some of these low-cost tools in health applications. I went to a conference in Kenya on point-of-care diagnostics, presenting some of these tools, and I was hoping again that people would pick it up. Generally I am keeping my promises away from medical applications, being aware of the regulatory issues, which in fact make complete sense. Patients deserve good-quality diagnostics. If you promise something to be a diagnostic tool that leads to therapeutic decisions, we have to make sure that the tools work, as we have just heard about the worst-case example of the Theranos Inc. scandal.

We could do a TED conference on the DIY microscope, where every couple of months someone gives a fancy presentation on how to “solve” the malaria problem. But they don’t even act or do anything to tackle the malaria issue. Malaria is the disease of the poor, and we also know how to diagnose malaria, but we just can’t afford the hospitals to treat them. So I usually keep the project within the educational environment, to empower people, rather than in real world health applications. But if someone wants to put it out there, it’s their project to do so.

Still there are people in the health sector who are trying to reduce the cost of hardware, for instance Echopen in Paris…

I really believe when it comes to health care that open hardware can reduce costs, but I also think that the original idea is to redesign it locally. The way a tool might look in Kenya is not the same the tool might look in Nepal. Different weather conditions, basic stuff like that. Through going to these conferences I learned a lot, which made me also reduce my promises, because I don’t have the experience. But also because I think that when you have an open hardware, and when local people start to develop this into a local product for health applications, this is the most interesting path to follow. But then again, when I was at the Transformaking conference in Indonesia in 2015, instead of discussing how to implement what already exists, the typical rhetoric is that everyone now needs to be an innovator.

It’s one of the reasons why Yashas Shetty and I (the two co-founders of Hackteria) started our humorous side-project called the Center for Alternative Coconut Research (CACR). Because during discussions we had on a beach in Goa, we realized that there is a lot of knowledge about what to do with a coconut tree, with the nuts (they are not nuts, they are fruits!), the leaves, the wood, etc., a lot of hacks to fix something in your household, health hacks as well, like coconut oil toothpaste, or infusion in case of extreme blood loss… A lot of solutions for sanitation, health, fashion, can be done with the coconut tree system. So we started the Center for Alternative Coconut Research, a bit as a joke, because there are not many new things left to discover, but also as a metaphor for the fact that there is not much to “innovate” (for example, there is already a website listing 333 different uses for the coconut).

We presented CACR at World Arduino Day 2015 to say: “Don’t feel ashamed to use local existing knowledge. And to make the world a better place, it doesn’t have to be a new innovation or app to solve a problem that we don’t even have.” It was a way to comment on this start-up innovation hype we see at the moment, this innovation frenzy. And in this big and heavy topic of the Global South, the Majority World, the knowledge of how to approach it is out there. There are ways to make latrines, there are ways to clean the water from parts of certain trees, so the new technologies are not always needed. What they need is not a piece of technology that a guy in Switzerland invents, but somewhere else in the translation and mutual understanding.

So what has been “lost in translation”?

Unfortunately that open sharing of knowledge seems to be not working so well these days. There is one website, called appropedia.org, a huge wiki with appropriate technology instructions for poverty reduction, solar energy, nutrition, health, waste management, agriculture, etc. But few people seem to know about it. To make that work it has to be locally adapted because different climate zones need different approaches. The available knowledge is rarely implemented. And the Zeitgeist, overvaluation of innovation, is even going further away from this kind of thinking—we must always do something novel.

Currently we are developing a very cheap electronic toy to work with children, similar to the very well known and successful Makey Makey. Makey Makey is expanding to India, but it turns out to be selling something very expensive to schools there, that could also cost just 2 dollars to make. Their new ones are not even open hardware anymore, though the original was, and they don’t tell you to “make it”. They almost force you through the product design and packaging to buy it. Nevertheless the educational aspect is very well described, how to implement it, but 50 dollars is still too much for what it is. So we got inspired to develop a 2-dollar compatible version, which is also technically improved, named Cocomake7. But we want people to produce it locally themselves and also potentially start a business with it. It is completely wrong that someone in Switzerland would sell it in Indonesia.

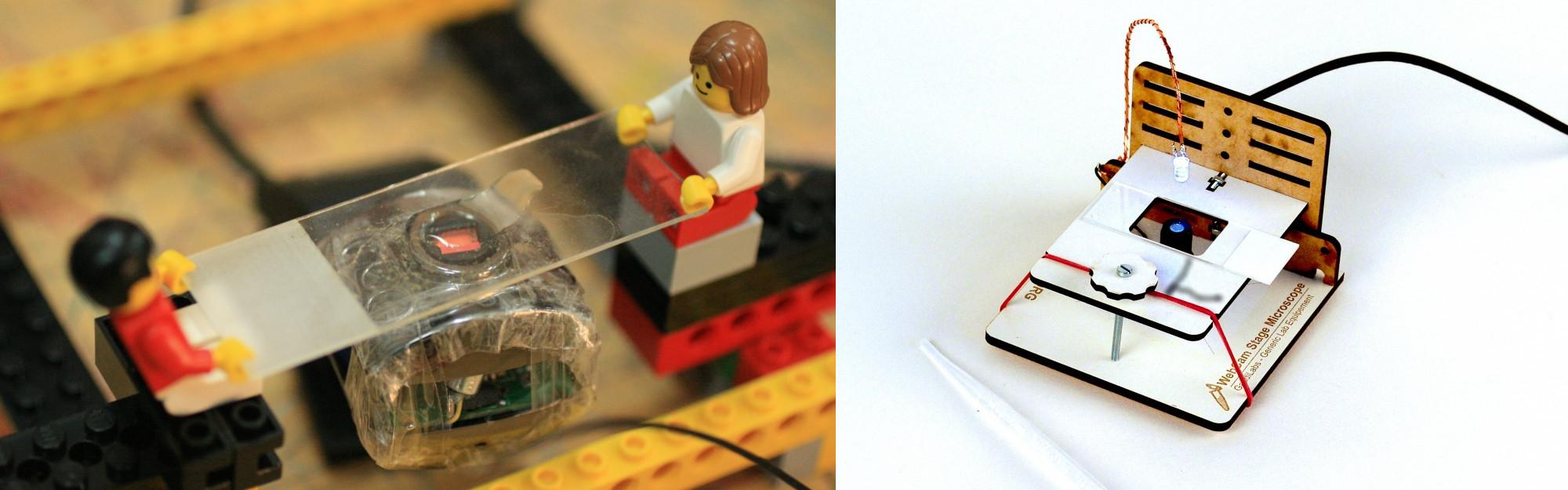

You work with hardware engineer Urs Gaudenz from GaudiLabs in Luzern, who developed a whole set of laboratory equipment made using digital fabrication tools such as laser-cutters and 3D printers. His pictures value the design, unlike yours…

I like the very DIY, hot-glued, cardboard versions, to give people the message that “you can build this, it’s a scientific instrument but it doesn’t look like one, and it still works”. So the DIY esthetics has its own message.

GaudiLabs’ pictures look beautiful, with a white background and fancy lighting. They look like a product, but it’s an engineer who assembled it by hand. It’s not a product, it’s an open source file and instructions. Of course, instantly everybody wants to buy these objects. But if you ask for a Swiss high-end engineer to build these things by hand, it would cost maybe something like 20,000 €. But Urs doesn’t do it for commercial interest. Some people want to buy it for, let’s say 300 €, which barely covers the materials, not to mention the years of development to get it to work. Urs Gaudenz is teaching part-time at the University of Luzern and is making these works in his free time, and we know we completely undervalue the work of housewives or househusbands. Since they looked almost like real scientific devices, some labs started to show interest in buying these tools “for” the students, although we had already specified that we encourage them to build these devices “with” the students.

So it’s still not that simple to cut costs?

Appropedia has a full section on open source laboratory equipment, where you can find a specific book by Joshua Pierce, Open Source Lab. It gave a new visibility to open hardware in the established science communities, mentioning the aspect of openness and adaptability, but mostly with the promise of being much cheaper—which is kind of true, but not my personal main vision of the field. If a science laboratory bought their equipment in China or searched for second-hand options, it would also be much cheaper. But universities usually buy equipment following their national pride from manufacturers of their own country, French companies for the French, etc. So there is big money going into equipment and infrastructures in science laboratories in the rich West, because this is how we run our budgets, and there seems to be little market pressure on science equipment to be cheap. In China, they have started maybe 500 universities in the last few years, and all of them need general science equipment for education, so there is a huge industry for Chinese manufacturers, and they are much cheaper that what we buy. But what we manufacture in a fablab is more expensive than professional equipment from China, if you calculate the full cost. But these days, the universities are getting into it, and I think it is partly due to a pressure from below. Bioengineering students are following the open source movement online, they see all this cool stuff on Kickstarter. I think the pressure for what is termed open science comes mostly from the students and the non-institutional public. But the traditional system of scientific institutions is very slow to adapt to this new movement.

How were you involved in organizing the Gathering for Open Science Hardware (Gosh!) at Cern?

We were recently contacted to organize a Gathering for Open Science Hardware that they called GOSH. We thought we were the first to organize a gathering for open hardware with that name, not knowing that in the open hardware hacker community these discussions started more than 10 years ago. But luckily I then remembered an event organized in July 2009 called Grounding Open Source Hardware at the Banff Centre in Canada that gave birth to Ohanda (Open Source Hardware and Design Alliance), which sadly died out. In Geneva we managed to have a very nice diversity, we had people from universities, people from maker communities in Nepal, from India, Indonesia (sadly enough no one from Africa), early pioneers from the open hardware community, diversity and gender activists, PhD students from the University of Cambridge, etc. We did focused breakout sessions, hands-on demonstrations, we also cooked food together!

What is the next big thing for you?

There is something happening in Nepal in October that I want to join, the Karkhana’s DIY Space Program in Kathmandu. We have collaborated with their staff various times already, they participated at Hackterialab in Bangalore and Yogyakarta, so it’s time for me to go there. It’s a hackerspace for education, they work a lot with youngsters, around 1,000 kids per week! They realized that Nepal was not really ready for hacker culture like the “American” model, so they thought they had to teach the next generation. Now they teach Arduino workshops, design thinking methods and general creativity training. They launched their citizen space program, and in October they will turn their robot festival into an art and technology festival. I’m very much looking forward to going there. And the Himalayas are at least already very close to space! And we Swiss people have some kind of connections with other mountain people!