Digital technology gently revives Japan’s “Battleship Island”

Published 21 June 2016 by Cherise Fong

Gunkanjima, the concrete island made famous by UNESCO and James Bond, can be explored virtually since November 2015 at the Gunkanjima Digital Museum. We went inside to see how digital technology is reviving the ghosts of coal mining’s past.

Nagasaki, special report (words and photos)

At the peak of its prosperity in 1959, the island of Hashima hosted a population of 5,259 living on its 6.3 hectares, and every single household had a television set. Today, the same island, better known as Gunkanjima (literally “Battleship Island”, based on its angular silhouette resembling the battleship Tosa), is the protected site of a dense agglomeration of concrete buildings in ruins, eroded by time, typhoons and nostalgia. An island several kilometers off the coast of Nagasaki, uninhabited since 1974, whose abandoned skeleton fascinates the imagination with its legendary history (see cameos in the James Bond film Skyfall (2012) or the Japanese film Attack on Titan (2015)).

The company Gunkanjima Concierge attempts to reconcile these two extremes of the island’s past and present: on one hand by organizing (along with other private companies) real (but limited) tours to Gunkanjima by boat; and since November 2015 via its Gunkanjima Digital Museum, located just a short walk away from the pier, which uses the latest digital technologies, archival images and personal stories to offer a virtual visit of the island and portray the life and work of its former residents.

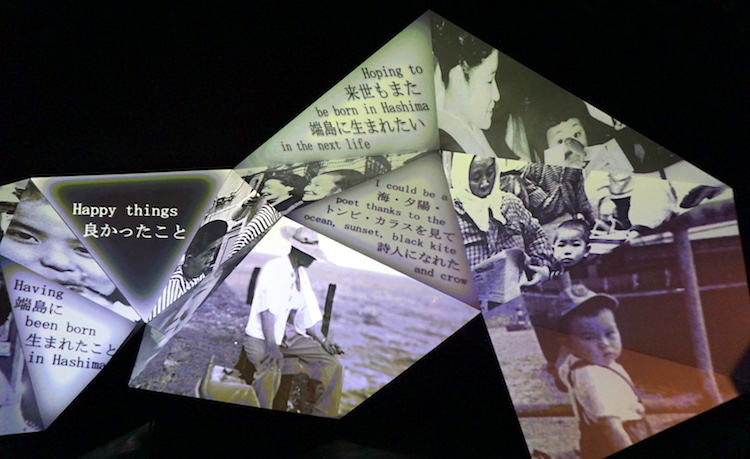

“Gunkanjima Symphony” exhibit at Gunkanjima Digital Museum (2015):

But what is the history of Gunkanjima?

In 1810, coal was discovered under a shelf of aqueous rocks near Takashima, an island already exploited for its mining resources off the coast of Nagasaki. In 1890, the Mitsubishi Mining Company bought the Hashima coal mine and annexed it to Takashima. Between 1897 and 1934, Mitsubishi built a sea wall around the entire island, three more mine shafts, a temple, a movie theater, an elementary school, the very first reinforced concrete 7- and 9-story apartment buildings, and reclaimed land to expand the island up to three times its original size.

Before and during the Second World War, Mitsubishi brought in hundreds of prisoners, especially from Korea and China, to work in extremely harsh conditions. In 1941, Hashima produced a record output of 411,100 tons of coal. In the prosperous post-war 1950s and ’60s, Mitsubishi built a hospital, a swimming pool, a dolphin pier… and residents benefited from the highest penetration rate of electronic devices in Japan. In 1974, as oil came to replace coal as the primary energy source, Mitsubishi closed the mine and evacuated the island. Gunkanjima has been uninhabited ever since. In July 2015, Hashima Coal Mine was designated a world heritage site by UNESCO.

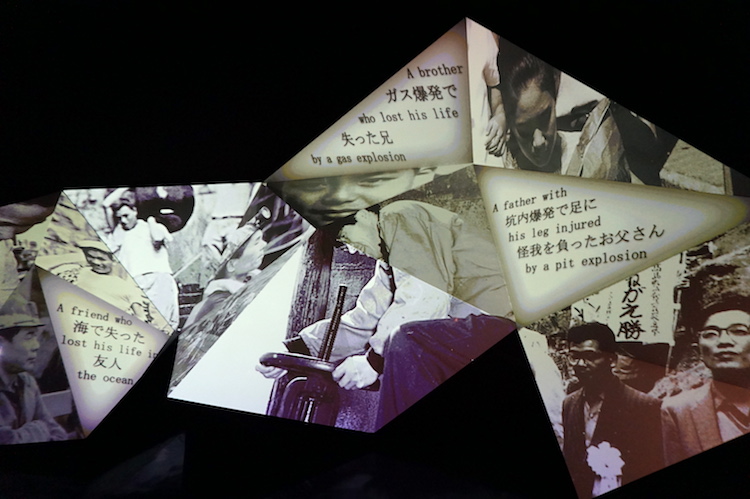

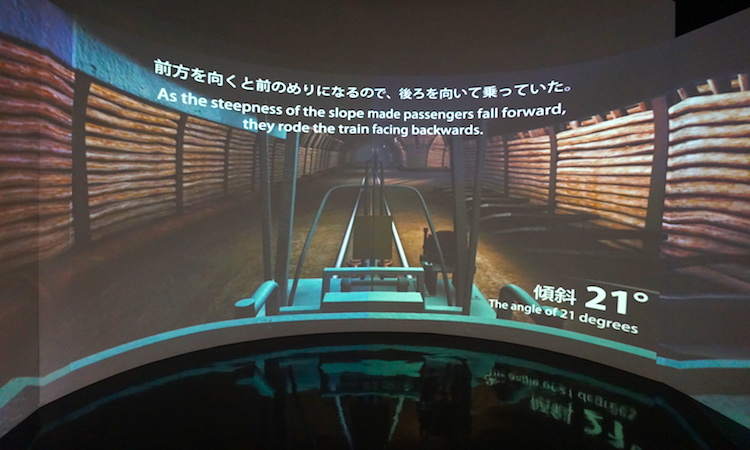

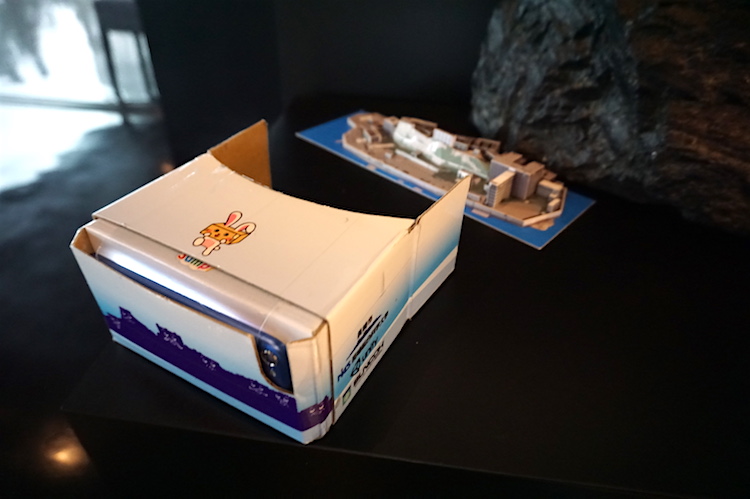

While the Gunkanjima Digital Museum doesn’t cover the entire history of the island, it spotlights the happier days of Hashima’s local community against the background of an industrial rush over several generations and a century of coal mining. Archival photos and videos mostly from the 1960s are projected on extra-large surfaces, some accompanied by nostalgic memories or projection mapping on a 1:150 model of the island (we can’t wait to see life-size video mapping, if not augmented reality, on the real thing). Among the high-tech installations are interactive HD images shot by a drone and juxtaposed with a 3D rendering of the island (we’re still waiting for the full VR version), and a virtual descent into the mine shaft (a vertical journey of more than 1 km, where temperatures reached 38°C in 90% humidity).

mine lamp battery.

The nomination of Gunkanjima, among 23 “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution”, to gain the status of world heritage site in 2008 raised new interest (and much controversy) around the island. Since then, several different companies offer guided tours, but all are restrained to the same newly paved path that extends some 200 meters from the pier. If the waves are too strong, the boat doesn’t dock, but still allows passengers to appreciate the mining environment that surrounded Hashima at the time, as well as impressive sea views of the island. One almost feels like James Bond on the yacht approaching a concrete skyline in the middle of the ocean.

If disembarking is not an option, Gunkanjima Concierge gives each passenger a free ticket to its Gunkanjima Digital Museum, which perfectly complements the maritime approach with its immersive experiences and visual archives. But (full-price) entry to the museum is also available for anyone who chooses to remain on land.

And it’s not the only way to visit the island virtually: Google had already sent over its camera backpacks in 2013 to explore Gunkanjima from the ground, and at least one documentary, made in 2008, follows a former resident through the ruins of his old building.

Indeed, the added value is human. Gunkanjima Concierge’s team of guides, both on the boat and at the museum, includes former residents of the island, such as Tomoji Kobata, who was a 24-year-old miner in 1961. He talks about how they worked in silence to avoid swallowing coal dust, how Mitsubishi ordered a health check every month, how he played cards and mahjong but especially slept during his free time, while other miners fought over the few young women on the island.

Projection mapping on a model of the island at Gunkanjima Digital Museum (2015):

But how can we truly revive the multi-faceted history of this sea-walled ghost town? Hashima’s strong community life recalls that of the defunct Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong (whose population density at the time was more than double that of the Japanese island)—albeit without the crime, drugs and disease that plagued it… Gunkanjima, and its people, have other memories.

Gunkanjima Digital Museum website

More information about Gunkanjima